Review: Macbeth

Jun 5th

Kenneth Branagh in Macbeth

(©Stephanie Berger)

It’s doubtful you’ll ever see as compelling and visceral a interpretation of Macbeth as the one being performed for much too brief a run at the Park Avenue Armory. Co-starring Kenneth Branagh and Alex Kingston, this production offers theatrical spectacle on a grand scale that stands in marked contrast to the stripped-down, modern-dress Shakespearean productions that are so often seen around New York. This is a great classic as might be presented by Medieval Times, and that's meant as a compliment.

Co-staged by Branagh and American director Rob Ashford, the production was originally presented last year at the Manchester International Festival in a small church accommodating some 250 theatergoers. Its presentation in the Armory’s vast, 55,000-square-foot drill hall is inevitably far less intimate, but the experience is galvanizing nonetheless.

The proceedings begin with audience members segregated into “clans” such as Cawdor and Glamis and segregated into various rooms awaiting entrance into the drill hall. The groups are escorted separately down a dimly lit path through what looks like a barren field before being led to their seating areas. (There’s a certain gimmickry to these elaborately stage-managed elements that ultimately result in the show starting a half-hour later than advertised.)

The playing area consists of a long dirt path down the center of the hall—the torrential rainstorm accompanying the exciting opening battle sequence quickly transforms it into mud—surrounded on both sides by tiers of benches stretching high into the upper reaches of the building (the backless seats prove awfully uncomfortable over the course of more than two hours). On one end of the playing area is an altar decorated with religious images, while the other features a massive, Stonehenge-like rock formation.

Condensed to a swiftly paced, intermissionless two hours—the judicious cutting is hardly noticeable—the play is given a dramatically rousing, highly physical treatment. The actors bound from one of the muddy strip to the other, giving audience members on both sides ample opportunity to be close to the action (at least for those not seated in the upper sections), although at times it gives one the feeling of watching a tennis match.

Making his long belated New York stage debut, Branagh, whose thrilling film versions of Shakespeare include Henry V and Hamlet, is not surprisingly superb. His naturalistic speaking of the verse is wonderfully comprehensible, and his psychologically astute characterization brings unexpected emotional shadings to a role that has been played in far too perfunctory a fashion by many actors over the years, most recently Ethan Hawke in the lamentable Lincoln Center production.

He’s beautifully matched by Kingston’s emotionally and physically intense turn as Lady Macbeth. Emanating a fierce hysteria and simmering sensuality, the actress makes vividly clear the intense erotic hold the character has over her easily manipulated husband. Among the supporting players, the standouts include Richard Coyle’s commanding Macduff, John Shrapnel’s dignified Duncan, and Scarlett Stallen’s moving Lady Macduff. As the three witches, Charlie Cameron, Laura Elsworthy and Anjana Vasan exude a lithe physicality and spectral spookiness that makes their every appearance memorable.

Gripping theatrical touches abound, from the glowing dagger that mysteriously floats in mid-air to the blazing flames accompanying the more dramatic moments to the vigorously staged fight scenes in which the actors pound into the walls lining the muddy strip with ear-shattering thuds. The elaborate production elements, from Christopher Shutt’s booming sound design to Patrick Doyle’s dramatic musical score, add greatly to the overall effect, although occasional bits of dialogue are swallowed up by the cavernous space despite the amplification.

But despite its occasional problematic aspects, watching Branagh tear into one of the Bard’s meatiest roles is a privilege that is only enhanced by the incredibly imaginative theatricality of this unforgettable production.

Park Avenue Armory, 643 Park Ave. 212-933-5812. www.armoryonpark.org. Through June 22.

Review: Hedwig and the Angry Inch

Apr 23rd

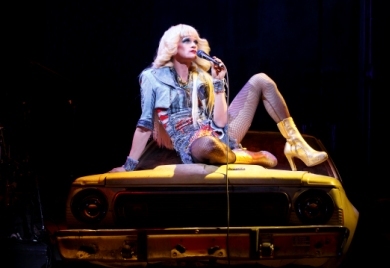

Neil Patrick Harris in Hedwig and the Angry Inch

(©Joan Marcus)

The colorful title character of Hedwig and the Angry Inch can be described as many things, but loveable is not usually one of them. That is, until now. Starring in the new Broadway production of John Cameron Mitchell and Stephen Trask’s award-winning musical about the East German transgender lead singer of a rock and roll band is none other than Neil Patrick Harris. Late of the hit sitcom How I Met Your Mother and beloved on the Rialto for his virtuosic hosting of the Tony Awards, this multi-talented performer is indeed a Hedwig you’d want to bring home to meet your mother.

For those of you who’ve somehow missed both its 1998 hit off-Broadway production and the 2001 film version directed by and starring Mitchell, the show takes the form of a rock concert performed by Hedwig and his hard-driving rock band, the name of which refers to a botched sex change operation which left him with, well, you know.

Originally presented in the seedy ballroom of the then run-down Jane Street Hotel, the show has been given an expensive facelift for this first Broadway outing flashily directed by Michael Mayer. Julian Crouch’s elaborate set design amusingly recreates the bombed-out environs of an Iraqi city, complete with the wreckage of a car. The joke is that Hedwig and his band—led by his cross-dressing lover Yitzhak, here ironically played by Lena Hall, wearing men’s clothing-- are performing on the set of Hurt Locker: The Musical, which has recently opened and closed in one night. Fake programs for that fictitious production, which doesn’t seem all that unthinkable in this era of endless musicals adapted from movies, are littered throughout the theater.

Making a spectacular entrance by being slowly lowered onto the stage from the rafters, Harris’ Hedwig has the audience in the palm of his hand from the first moment to last. In between singing the numbers of Trask’s glam-rock influenced score, he delivers a running monologue detailing his tortured past, including his ill-fated relationship with a rock star who happens to be giving a concert in nearby Times Square. Periodically opening a door at the rear of the stage so he can hear the screams of the crowd, his pained expression speaks volumes.

He also delivers a brief history of the Belasco Theatre and makes a plug for his new fragrance, dubbed “Atrocity.”

“We’re not quite sure about the catchphrase yet,” he explains.

Harris works the crowd like a master, spontaneously riffing improvisations and giving the patrons in the front rows an uncomfortably up close and personal experience by, among other things, thrusting his crotch in their faces and even licking a hapless audience member’s bald head. He leads the audience on a sing-along for one song, instructing us to “follow the bouncing balls” which, as the accompanying projection demonstrates, is meant quite literally.

Making a dazzlingly quick costume change from the hood of the car and donning a series of increasingly outlandish wigs, Harris doesn’t quite mine the darker aspects of his character in the way that such predecessors in the role as Mitchell and Michael Cerveris did. He’s so inherently likeable that the evening inevitably takes on the air of a celebration, which is not exactly the intention. But the upside is that Hedwig is far more funny and entertaining than ever before. It’s a pleasure to have him back.

Belasco Theatre, 111 W. 44th St. 212-239-6200. www.Telecharge.com. Through Aug. 17.

Review: The Cripple of Inishmaan

Apr 21st

Daniel Radcliffe in The Cripple of Inishmaan

(©Johan Persson)

His face may be prominently displayed on the Playbill cover and theater marquee, but Daniel Radcliffe melts seamlessly into the ensemble of The Cripple of Inishmaan, Martin McDonagh’s 1996 play now receiving its Broadway premiere after two acclaimed off-Broadway productions. Director Michael Grandage’s revival, imported here after a successful London engagement, fully mines the dark humor of this quintessentially Irish work in which the characters’ perverse cruelty takes on an air of mordant poetry.

In his most accomplished stage performance to date, the Harry Potter star delivers a physically and emotionally committed turn as “Crippled Billy,” an orphaned 17-year-old whose useless arm and stiff leg reduce his gait to a painful shuffle. In this play, inspired by documentary filmmaker Robert Flaherty's arrival on the bleak island to film his 1934 film Man of Aran, Billy finds his life briefly transformed when he is whisked off to Hollywood for a screen test.

But before that happens we are introduced to a gallery of colorful characters: Billy’s unmarried aunts Eileen (Gillian Hanna) and Kate (Ingrid Craighe), who run a general store whose stock seems to consist almost entirely of canned peas; the endlessly gossipy Johnnypateenmike (Pat Shortt), who constantly regales the townspeople with stories both big (Hollywood coming to town) and small (a petty incident involving a goose); his elderly mother (June Watson) who he keeps perpetually supplied with booze; red-haired spitfire Helen (Sarah Greene), with whom Billy is hopelessly besotted; her younger brother Bartley (Conor MacNeill), who she tortures unmercifully; and the town doctor (Gary Lilburn) who clearly has his hands full.

There’s little plot to speak of, and the two-and-a-half hour play proves repetitive in its depiction of its characters’ many quirks. But much like Flaherty fictionalized many elements of his so-called documentary, McDonagh portrays the illusions of these colorful figures who are nearly always saying one thing while meaning something else entirely.

To say that the members of the ensemble work together seamlessly is an understatement. The mostly Irish performers deliver such authentic-feeling, lived-in turns that it’s easy to imagine that their characters have lived in a state of not-so-peaceful co-existence for their entire lives. Their casual harshness is well illustrated in the aunts’ reaction when they’ve discovered that Billy has snuck off to Hollywood.

“I hope the boat sinks before it ever gets him to America,” one of them declares. “I hope he drowns like his mammy and daddy before him,” the other agrees, before adding, “Or are we being too harsh?”

While Greene is a standout as the sexy Helen for whom physical abuse is her natural way of expressing herself, it’s indeed Radcliffe who steals the show. His Billy displays a complex mixture of steeliness and vulnerability, the latter heartbreakingly conveyed when he finally musters up the courage to ask Helen out on a date only to be met with harsh laughter. It’s a brave, self-effacing turn that well demonstrates this young actor’s admirable willingness to go out on a withered limb.

Cort Theatre, 138 W. 48th St. 212-239-6200. www.Telecharge.com. Through July 20.

Review: Of Mice and Men

Apr 17th

James Franco and Chris O'Dowd in Of Mice and Men

(©Richard Phibbs)

John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men is a beloved classic that is a staple in high school reading lists and has been adapted not once but twice for films. So why is it that this superb drama is only now receiving a Broadway revival for the first time in nearly forty years? It’s an oversight that has been finally rectified with the superbly staged and acted production starring James Franco and Chris O’Dowd that marks one of the highlights of the season.

Steinbeck’s 1937 work holds up beautifully in its superb dramatic construction and deeply moving characters. Set in California’s Salinas Valley, it depicts the strong friendship between migrant farm workers George (Franco) and Lennie (O’Dowd) who at the play’s beginning have just arrived at a ranch where they hope to work long enough to build up a stake so they can buy a small farm.

The two men represent an odd pair whose bond is never fully explained. George is a canny schemer capable of quickly sizing up people and situations, while the physically imposing Lennie is mentally impaired. He’s an overgrown man-child whose superhuman strength makes his love for petting small animals such as mice and rabbits often producing fatal results.

While the other workers regard this pair of grown men traveling together with suspicion, they quickly welcome them into their fold with George assuming his usual role as the socially maladroit Lennie’s protector. The exception is Curley (Alex Morf), the ranch owner’s son, whose bullying quickly sets George on edge. Fueling Curley’s hostility is his insecurity regarding his beautiful, sexy wife (Leighton Meester of Gossip Girl fame) whose loneliness and isolation prompts her to seek company in the men’s bunkhouse.

The play’s tragic climax is vividly foreshadowed, both by incidents from the past—Lennie was nearly strung up after an unfortunate encounter with a young woman who he nearly killed when he wouldn’t let go of her—and such gut-wrenching scenes as the men failing to intervene when one of their ranks (Joel Marsh Garland) insists on shooting the lame, elderly dog who is the beloved companion of Candy (Jim Norton), an aged, infirm worker who’s about to be let go.

Steinbeck’s deeply humanistic writing is vividly displayed in these and other moments and in such characters as Crooks (Ron Cephas Jones), the ranch’s sole black employee who is shunned by the other men and has bitterly retreated into isolation.

Director Anna D. Shaprio’s (August: Osage County) pitch-perfect production superbly captures the work’s deep pathos and dark humor. The latter is accentuated by O’Dowd’s superb performance. The Irish actor, best known on these shores for his appealing turn as the cop besotted with Kristen Wigg in the film Bridesmaids, is such an inherently funny performer that he scores frequent laughs. But rather than being jarring, it works beautifully, accentuating Lennie’s childlike innocence in a way that such cinematic predecessors in the role as Lon Chaney, Jr. and John Malkovich did not.

Making his theatrical debut, Franco, whose endless array of eccentric projects have earned him as much derision as admiration, more than holds his own. Although the actor doesn’t yet have the ability to fully command the stage, he delivers a thoughtful, measured performance that well portrays George’s loyal devotion to his simple-minded companion. Among the supporting players, particularly strong contributions are made by Norton, heartbreaking as the old man desperate to share the new arrivals’ dream of living on their own farm; Cephas Jones, vividly conveying Crooks’ anger and intelligence; and Jim Parrack, projecting stolid decency as Slim, the ranchers’ overseer.

By the time the evening reaches its violent, haunting conclusion, this fully lived-in and authentic-feeling production has fully cast a spell. It has the rare effect of leaving the audience feeling both deeply saddened and exhilarated.

Longacre Theatre, 220 W.48th St. 212-239-6200. www.Telecharge.com. Through July 27.

Review: Lady Day at Emerson’s Bar & Grill

Apr 14th

Audra McDonald in Lady Day at Emerson’s Bar & Grill

(©Evgenia Eliseeva)

Audra McDonald doesn’t look or sound anything like Billie Holiday. So it’s a credit to the five-time Tony Award winner that she perfectly embodies the jazz singer legend in Lady Day at Emerson’s Bar & Grill, Lanie Robertson’s musical drama receiving its Broadway premiere. This gifted performer delivers such a chameleon-like vocal turn that if you shut your eyes it’s all too easy to believe you’re listening to the real thing.

Previously seen here in a 1986 Off-Broadway production starring Lonette McKee, the show depicts a late-night set performed by Holiday and a jazz trio in a small Philadelphia bar just four months before her death in 1959 at the age of 44. In between performing some fifteen songs, the clearly booze and drug-addled singer delivers a running biographical commentary about her tragedy-filled life.

For director Lonny Price’s atmospheric staging the Circle in the Square has effectively been partially converted to a cabaret, with a small stage at one end of the playing area which is otherwise filled with small tables inhabited by lucky (and free-spending) audience members. The result is an uncommon intimacy, with McDonald frequently wandering into the crowd begging cigarettes, chatting up patrons and one point literally falling into someone’s lap.

The rambling monologue accentuates Holiday’s bitterness and dissipation. Complaining about having to perform such trademark songs as “Strange Fruit” and “all that damn shit,” she angrily snaps down her accompanist Jimmy Powers’ (Shelton Becton) piano lid when he launches into the opening notes of “God Bless the Child.” She describes past lovers and her bitterness over having lost her cabaret license after she was arrested for drugs. Stopping the show to wander over to the bar opposite the stage, she pours herself a tall glass of vodka and later departs for several minutes while her band plays on, only to return holding a small Chihuahua in her arms. (The canine, played by a rescue dog named Roxie, is a real crowd pleaser).

Although the script does a reasonably good job of conveying Holiday’s tragic essence at this late point in her life, it’s not fully satisfying on dramatic terms. But it does serve as an efficient vehicle for McDonald’s uncanny impersonation of her sweetly husky vocal style. Perfectly capturing the singer’s slurry, jazzy intonations while wringing maximum emotion from such songs as “What a Little Moonlight Can Do,” “Foolin’ Myself” and “Crazy He Calls Me,” McDonald delivers an unforgettable tour-de-force turn.

By this point, more people have probably seen theatrical facsimiles of Billie Holiday—Dee Dee Bridgewater recently played the singer in another, short-lived Off-Broadway show--than ever saw her perform live. It’s an irony that even Lady Day herself might have appreciated.

Circle in the Square, 1633 Broadway. 212-239-6200. www.Telecharge.com.