Review: Death of a Salesman

Whenever there’s a new revival of Death of a Salesman people marvel at the fact that it seems so newly relevant. But it’s not that society is changing but rather that Arthur Miller’s 1949 masterpiece, now receiving a triumphant Broadway production directed by Mike Nichols, is so timeless.

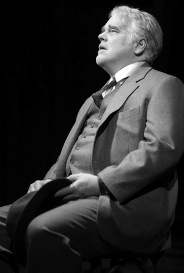

There was some question about the necessity for this revival, coming relatively soon after the acclaimed 1999 production starring Brian Dennehy. And the casting of 44-year-old Philip Seymour Hoffman as the 62-year-old Willy Loman seemed dubious, despite the fact that the play’s original star, Lee J. Cobb, was a mere 37 when he essayed the role.

But any doubts are immediately erased by this shattering revival, which marks a major return to form for its legendary director after his disappointing production of The Country Girl a few years back.

The play itself is nearly indestructible, with Miller’s groundbreaking combination of harsh naturalism and poetic illusion registering as powerfully today as it did upon its premiere. And this production harkens back to the original in significant ways, reprising the original groundbreaking set design by Jo Mielziner as well as the haunting background music by Alex North, who would go on to write the scores for such films as A Streetcar Named Desire, Spartacus and dozens of others.

Mielziner’s set, comprised of the skeleton of the Loman’s Brooklyn home and a minimum of props, skillfully allows for the use of lighting and projections to infuse the proceedings with a dreamlike, cinematic feel that conveys Willy’s flights between reality and fantasy, the past and the present. Seeing it come to life feels like a trip into theatrical history.

From the opening moment--when Hoffman’s lumbering Willy wearily drops his sample cases onto the kitchen floor--to the shattering final scene in the graveyard, Nichols’ production doesn’t make a single false step.

Hoffman, whose ample physique makes him appear older than he is, is a shattering Willy, perhaps the most vulnerable ever. Unlike Dustin Hoffman, who projected a bantamweight feistiness, and Dennehy, with his intimitading physical presence, his Willy is a relentlessly pitiful, tragic figure. But the actor also beautifully captures the humor of the role--the way that Willy’s quick-silver contradictions reflect not just his crumbling mind but also his stubbornly self-defeating personality.

Linda Emond, also playing older than she is, is deeply moving as the wife, Linda, investing even the character’s most familiar speeches with fresh emotional immediacy. British actor Andrew Garfield, making his Broadway debut after wowing film audiences in The Social Network (and just prior to his taking over for Tobey Maguire in the Spider-Man film reboot), is superb as the oldest son Biff, whose emotional self-realization at the end of the play is its pivotal scene. And unlike many English actors playing New Yorkers, he thankfully doesn’t overdo his accent.

Everyone in the supporting cast is sublime: Fran Wittrock, joyfully energetic as Happy, the other “Adonis son”; Bill Camp, beautifully understated as Charley, the best friend who offers Willy a lifeline that the proud salesman refuses to accept; John Glover, floridly melodramatic as Ben, Willy’s brother who haunts him with the misery of missed opportunities; and Fran Krinz, versatile as Bernard, the nerd who grows up to be lawyer appearing before the Supreme Court.

Yes, you’ve seen Salesman before. And the play is definitely not light-hearted entertainment (although it does feature surprisingly humorous moments). But when a production this well acted and staged comes along, attention must be paid.

Ethel Barrymore Theatre, 243 W.47th St. 212-239-6200. www.Telecharge.com. Through June 2.

| Print article | This entry was posted by Frank on 03/16/12 at 04:10:01 am . Follow any responses to this post through RSS 2.0. |