Category: "Broadway"

Review: Wit

Jan 27th

Margaret Edson has just written one play in her life, the brilliant Wit, now receiving its Broadway premiere a mere seventeen years after it was first produced and went on to win nearly every theater award, including the Pulitzer Prize. This new incarnation could well result in another accolade: a Tony for Best Revival of a Play.

Anyone who saw the brilliant Kathleen Chalfant in the original Off-Broadway production might wonder whether Cynthia Nixon would be as effective in the role of Vivian Bearing, a poetry professor suffering from Stage IV ovarian cancer. But while Nixon offers a quite different, less officious interpretation than her predecessor, she is no less affecting.

Her character acts as the play’s narrator, directly addressing the audience in telling the story of the diagnosis of her affliction and her subsequent agreement to an experimental chemotherapy treatment that will not cure her but rather provide much needed data for the medical researchers handling her case.

It’s grim stuff, to be sure, but the play beautifully balances pathos with humor in its depiction of the emotional and mental anguish that Bearing undergoes as she becomes little more than a research subject for her doctors. Along the way, flashbacks reveal her earlier life, from when she was a young girl hungry for knowledge to her distinguished career as a professor specializing in the works of the 17th century John Donne--famous, of course, for the line “Death be not proud.”

The playwright once worked in the cancer unit of a research hospital, and clearly knows the terrain well. She beautifully captures the unthinking casual breeziness of the doctors, including one young researcher (Greg Keller), who used to be Bearing’s student and who treats her with the same rigorous exactitude that she applied in her classroom.

There is no shortage of heartbreaking scenes, most notably one towards the end involving a visit to the dying Bearing by an elderly woman (a superb Suzanne Bertish) who was once her professor and who climbs into bed with her and reads her a children’s story while gently stroking her hair.

Under the sensitive direction of Lynne Meadow, the supporting players--including Michael Countryman as a doctor supervising the case and Carra Patterson as a friendly nurse and the only person who actually treats the patient as a person—deliver sterling work. But it is Nixon, perfectly conveying her character’s combination of emotional reserve, acerbic wit and brilliant intellectualism—“It’s highly educational, I am learning how to suffer,” she remarks at one point about her ordeal—who powers the production. Her sublime, deeply affecting portrayal, for which she bares both body and soul, is a revelation.

Samuel J. Friedman Theatre, 261 W. 47th St. 212-239-6200. www.Telecharge.com. Through March 11.

Review: The Road to Mecca

Jan 18th

The plays of Athol Fugard often require heavy lifting on the part of an audience. That’s particularly true of his 1987 drama The Road to Mecca, now being given its Broadway premiere in a revival by the Roundabout Theatre Company. This tale of an elderly woman artist rebuffed by her community represents the playwright at his talkiest and most didactic. Still, it has its moments of quiet beauty, and its return is welcome if only for the opportunity to see the luminous Rosemary Harris onstage.

Director Gordon Edelstein has assembled a stellar cast for the production: Carla Gugino plays Elsa, a schoolteacher and friend of Harris’ Miss Helen, and Jim Dale is Pastor Marius Byleveld, a role that was originally played by the playwright himself.

Miss Helen is based on a true-life figure, Helen Martins, who lived in the remote Karoo region of South Africa where the play is set. At the play’s beginning, it’s established that has become a depressed, reclusive figure, shunned by her fellow villagers because her iconoclastic artworks, with which she has copiously decorated her house and garden, offend their religious sensibilities.

Her friend Elsa, concerned for her friend’s plight, has traveled hundreds of miles from Cape Town to see about Miss Helen’s health and to urge her to resist any efforts to dislodge her from her home. The play’s 65-minute first act consists of a rambling, repetitive conversation between the two, the general banality of which will tax even the most tolerant theatergoer’s patience.

Act II picks up considerably with the arrival of the pastor, who speaks to the clearly emotional fragile Miss Helen in a soothing, solicitous manner that only partially conceals the intolerance underlying his arguments.

Although this part of the play is indeed livelier, thanks in no small part to Dale’s energetic presence, it’s also filled with the sort of heavy-handed metaphors with which Fugard frequently infuses his more labored works. There’s also a lot of candle lighting—Miss Helen uses them as the sole illumination in her house, and they figure in a less than incendiary plot revelation—but the overall dimness isn’t alleviated.

Harris is, as always, exemplary here, delivering a subtle, graceful performance that touchingly makes clear her character’s underlying vulnerabilities. Gugino is appealingly feisty, and Dale provides a welcome liveliness as the pastor whose motivations are more complex than they initially appear.

Michael Yeargan has provided a wonderfully detailed, eccentric set—one that supposedly replicates the real-life subject’s home, which is now a tourist attraction—even if Peter Kaczorowski’s necessarily dim lighting, designed to replicate the effects of all those candles—makes it rather hard to see clearly.

American Airlines Theatre, 227 W. 42nd St. 212-719-1300. www.roundabouttheatre.org.

Review: The Gershwins' Porgy and Bess

Jan 13th

Composer Stephen Sondheim will probably be appeased when he sees The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess, the reconceived revival of the classic opera by George and Ira Gershwin and, oh yes, librettist/lyricists DuBose and Dorothy Heyward. Many of the radical changes that Sondheim objected to so publicly in his letter to The New York Times have been abandoned, with the result that this version is more or less faithful to the original, minus 45 minutes or so of its running time.

But it’s not just the length that has been diminished. Although this production has its terrific elements and is well worth seeing (especially considering how seldom the show is done), it fails to fully convey the power of this magisterial work.

While the singing by Audra McDonald and Norm Lewis in the title roles is glorious, the magnificent score, adapted by jazz composer Dierdre L. Murray, is not fully given its due. The problematic sound system prevents the 22-piece orchestra from coming across with the necessary power, with the result that the music sounds like it’s being piped in from another theater altogether.

The visuals, too, are a problem. Rather than conveying the teeming life of Catfish Row, Riccardo Hernandez’ stark tin wall set more closely resembles an abandoned warehouse. And the costumes by ESosa are not artfully drab, just boringly so.

The book adaptation by Pulitzer Prize winner Suzan-Lori Parks (Topdog/Underdog) condenses the original in reasonable fashion, and even improves it times, such as in the powerful Act II scene between Bess and Crown (Philip Boykin) that is here charged with ambiguity and sexual tension.

For the most part, however, the production is never fully galvanizing, perhaps because the reduced staging by Diane Paulus lacks the operatic intensity that the show requires. It’s interesting to note that another theater-style production directed by Trevor Nunn in London met with similar complaints and a lack of box-office interest several years ago.

Still, one doesn’t often get the opportunity to hear gorgeous songs like “I Got Plenty of Nothing,” “Bess, You Is My Woman Now” and “I Loves You Porgy” sung by voices of the caliber of Lewis and McDonald’s. The former’s warm baritone envelopes you like a heavy coat on the winter’s night, while the latter’s gorgeous soprano is consistently ravishing. Just as importantly, they bring a heartbreaking depth to their characterizations—just try not to cry during the final moments, when Lewis’ Porgy sings “I’m On My Way,” about journeying to New York City to reclaim his lost love.

Although he tends to overplay at times, David Alan Grier is a generally terrific Sporting Life, and brings a welcome urgency to such numbers as “It Ain’t Necessarily So” and “There’s a Boat That’s Leaving Soon.” The physically formidable and vocally commanding Boykin is a scarily intense Crown, while Nikki Renee Daniels, Joshua Henry and Bryonha Marie Parham are impressive in their supporting roles.

Richard Rodgers Theatre, 226 W. 46th St. 800-745-3000. www.ticketmaster.com.

Review: Lysistrata Jones

Dec 15th

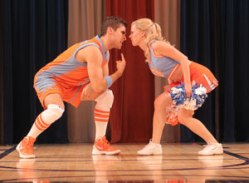

The near demise of commercial off-Broadway has resulted in a plethora of unsuitable Broadway productions of tiny shows that look awfully wan in big theaters. The latest example is Lysistrata Jones, originally presented by the enterprising Transport Group on the basketball court of the Judson Memorial Church gymnasium. This musical updating of Aristophanes’ comedy—about a group of college cheerleaders who decide to withhold sex from their boyfriends on the perennially losing Athens University basketball team until they win a game—benefited mightily from its unique venue. On the stage of the Walter Kerr Theatre, it seems way out of its league.

Resembling a special-themed episode of Glee, the show--featuring a book by Douglas Carter Beane (responsible for such similarly silly musicals as Sister Act and Xanadu) and music and lyrics by Lewis Flinn--is more notable for the charged energy of its youthful ensemble than its creative elements. And it wears out its comedic welcome long before the conclusion of its two hour-plus running time.

Still, there’s some fun to be had, beginning with the outrageous presence of the big-bodied Liz Mikel as the show’s acerbic narrator. Beane’s book, gleaning most of its vulgar humor from the overcharged sex drives of both the male and female characters, has a suitably burlesque quality. And while the score boasts few memorable songs, such numbers as “Right Now” and the climactic “Give It Up!” display a raucous energy.

Director Dan Knechtges (Xanadu, The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee) keeps things moving at a suitably frantic pace, and his choreography, influenced by both cheerleading routines and basketball moves, is consistently inventive.

Among the ensemble, the standouts are Patti Murin, who provides just the right amount of perky sexiness as the title character; Jason Tam, very amusing as her unlikely, social media-obsessed love interest; and Josh Segarra, goofily endearing as the head jock.

The staging has been reconfigured for the Kerr’s proscenium stage, and some lavish props, such as a giant neon sign advertising a bordello, have been added to little effect. Most detrimentally, the sound has been jacked up to deafening levels, with the result that many of the lyrics are barely discernible.

In its former home, tix for Lysistrata Jones topped out at $60. On Broadway, they go up to $130, or $147 if you want aisle seats—and that’s not even counting the “premium” tickets, which are $199. Take a cue from the female characters in the show—don’t give it up.

Walter Kerr Theatre, 219 W. 48th St. 800-432-7250. www.Telecharge.com.

Review: On a Clear Day You Can See Forever

Dec 12th

In the musical On a Clear Day You Can See Forever, we learn that the central character experienced a past life and suffered an untimely end, only to be reborn in a new incarnation. Such is the case, too, with this 1965 musical by Burton Lane (music) and Alan Jay Lerner (lyrics and original book), which is now being given new life in a revival starring Harry Connick Jr. and featuring a completely rewritten book by Peter Parnell. Unfortunately, history is likely to repeat itself--like its previous version, this Clear Day suffers from an unworkable book. The only difference is that it’s unworkable in a completely new way.

In the original, which starred John Cullum and the great Barbara Harris (both received Tony nominations, as did the score), a psychiatrist takes on a new patient, Daisy Wells, who has the gift of ESP and who under hypnosis reveals that she is the reincarnation of a free-spirited 18th century woman named Melinda Wells. The shrink soon falls in love with Melinda, much to the consternation of Daisy, who by then has fallen for him herself.

Not surprisingly, this silly scenario received a proper drubbing from the critics, and despite its lovely score the show ran a mere 280 performances. Nor did the property fare much better when it was made into a 1970 movie starring Barbra Streisand and Yves Montand.

Director Michael Mayer’s re-conception, set in 1974, provides a gender change for Daisy, who is now David (David Turner), a 29-year-old gay florist with commitment issues. In his past life he was a 1940s-era female jazz singer (still named Melinda Wells), and it is her with whom Dr. Mark Bruckner (Connick) falls in love. Meanwhile, David, despite the fact that he has a gorgeous boyfriend (Drew Gehling), finds himself falling for the shrink, who fails to inform his patient that the reason for their countless hypnosis sessions is so he can spend more time with Melinda.

Needless to say, this lends a fairly complex spin to what was already an outlandish scenario. Bruckner, who is now the show’s main focus, somehow falls for Melinda even though she’s embodied by David. (Of course, the audience sees what he sees, namely the lovely actress/singer Jessie Mueller as Melinda.) In one of the more bizarre musical numbers, he dances with both David and Melinda, in a sort of choreographic ménage a trois.

To say that this doesn’t work is an understatement. Not helping matters is that Connick doesn’t begin to have the acting chops to pull off what would be a challenge for even the most experienced actor. Most of the time, except of course when he’s singing, he looks awfully uncomfortable onstage, and when the moment comes when he’s about to kiss his male co-star it’s clear that the curtain can’t come down fast enough.

Turner is another problem. His fussy, mannered performance lacks the required charm, and he doesn’t have the voice to pull off such powerful numbers as “What Did I Have That I Don’t Have?” On the other hand, Mueller, a Chicago performer here making her Broadway debut, does nicely by Melinda, and infuses her jazz-tinged numbers with real feeling. Of the rest, Sarah Stiles steals her scenes as David’s BFF; Drew Gehling displays a killer voice on such songs as “Love With All the Trimmings”; and Kerry O’Malley makes the most of her thankless role as the shrink’s colleague who’s secretly in love with him.

Director Mayer handles the show’s physical complexities—the action frequently shifts back and forth between 1974 and 1944, with David suddenly transforming into Melinda—with his usual professionalism. But the look of the production is godawful. You can’t blame Catherine Zuber’s costumes, which are hideous, but then again pretty much all clothes from that era were. But Christine Jones’ set--featuring a profusion of pop-art style graphics and a garish color scheme that looks like an explosion at a paint factory—is a true eyesore.

Fortunately, the gorgeous score provides plenty of compensations, especially when it’s being sung by Connick in his heartthrob style. Augmented here by a couple of numbers written for the movie and others taken from the score of the film “Royal Wedding,” it’s a consistent delight. When Connick belts out the dynamic “Come Back to Me” or croons the gorgeous title number, almost, if not all, can be forgiven.

St. James Theatre, 246 W. 44th St. 212-239-6200. www.Telecharge.com.