Category: "Broadway"

Review: Rocky

Mar 14th

Andy Karl in Rocky

(©Matthew Murphy)

You’ll leave the new Broadway musical Rocky humming the score. Unfortunately, it won’t be the wholly unmemorable one by veteran composers Stephen Flaherty and Lynn Ahrens (Ragtime, Once on This Island) but rather such music featured in the original 1976 film and its sequels as Bill Conti’s stirring theme and the rock hit “Eye of the Tiger” by Survivor, both of which are generously spotlighted.

Oh, did I mention you’ll also be humming the scenery? Christopher Barreco’s elaborate, endlessly shifting sets for this hugely expensive production are indeed awe-inspiring.

The latest in a seemingly never ending series of musicalizations of beloved films, Rocky seemed like a dubious bet for such treatment. Although its storyline about a struggling small-time boxer who finds self-redemption via a one-in-a-million title bout with a reigning champ--as well as love with the mousy girl he inspires to come out her shell--has a powerful elemental quality, its gritty aspects don’t exactly inspire visions of song and dance.

This musical version of the film that made Sylvester Stallone a superstar doesn’t exactly dispel that notion. But thanks to its iconic characters and a brilliant staging courtesy of director Alex Timbers, it emerges as a genuine crowd-pleaser that, much like its titular hero, manages to go the distance.

Co-written by the incongruous team of Stallone and Thomas Meehan (Annie, The Producers), the musical is slavishly faithful to its inspiration, telling the Philadelphia-set story of Rocky Balboa (Andy Karl), the “Italian Stallion” who’s reduced to low-end bouts and making a living as an enforcer for a loan shark. He’s desperately in love with Adrian (Margo Siebert), the sister of his best friend Paulie (Danny Mastragiorgio), but although she returns his affections she’s far too repressed to act on them.

Rocky’s life changes when he’s suddenly plucked out of obscurity to fight the champion, Apollo Creed (Terrence Archie), after his original title bout opponent is injured. Creed, who picked Rocky because of his colorful nickname and appealing hard luck story, expects to make short work of the untested fighter. But as everyone in the audience undoubtedly already knows, that’s not to be the case.

The sluggish first act recreates many of the film’s iconic scenes with a slavish fidelity that inspires boredom. Rest assured that you’ll hear Rocky bellow “Yo Adrian” more than a few times and that you’ll be reintroduced to such familiar characters as his snappish trainer Mickey (Dakin Matthews). Flaherty and Ahrens’ ballad-heavy score is similarly uninspired, with the exception of one or two catchy songs like Rocky’s solo number “My Nose Ain’t Broken.”

But director Timbers really kicks things up a notch in the second half with a couple of exuberant training montages and particularly with the climactic boxing match featuring terrific pugilistic-inspired choreography by Steven Hoggett and Kelly Devine. To reveal the details of the incredibly inventive staging would be to spoil the surprise. Suffice it to say that it involves a movable regulation-size boxing ring, a giant multi-screen Jumbotron, and an all-around immersive quality that truly involves the audience in the action. To say that all the hoopla was greeted by rapturous cheers would be an understatement.

Karl, although a bit too slight to make for a convincing heavyweight, brings real charm to the role, channeling just enough of Stallone to satisfy the film’s fans while also making it his own. The supporting players, by contrast, pale in comparison to their cinematic predecessors. Seibert’s Adrian lacks Talia Shire’s sublime poignancy, and Mathews, Archie and Mastrogiorgio fail to supply the comic grace notes that Burgess Meredith, Carl Weathers and Burt Young infused into their performances.

On the way out, a fellow critic commented, “What are we even doing here?” It was an apt question. For all its flaws as a musical, the show feels genuinely critic-proof. It seems very likely that Rocky will be fighting at the Winter Garden for a long time to come.

Winter Garden, 1634 Broadway. 212-239-6200. www.telecharge.com.

Review: All the Way

Mar 7th

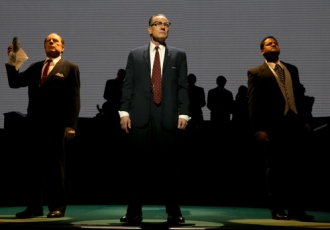

Michael McKean, Bryan Cranston, and Brandon J. Dirden in All the Way

(©Evgenia Eliseeva)

Playing Lyndon B. Johnson in Robert Schenkkan’s ambitious historical drama All the Way, Bryan Cranston commands the stage in the same manner that LBJ commanded politics. Making his Broadway debut, the Emmy-winning star of Breaking Bad delivers a powerful, canny performance that constantly mesmerizes, even if the nearly three-hour drama he inhabits at times suffers from a wearisome overload of incidents and information.

Set in 1963-1964 from Johnson’s ascent to the Presidency after the JFK assassination to his triumphant election the following November, the play largely concentrates on his determined efforts to pass the Civil Rights Act despite the fervent opposition of Southern congressmen and his battle to win the presidency in his own right. It vividly depicts the nuts-and-bolts of LBJ’s strong-arm manipulations in great detail, with its large cast of characters including such figures as his wife Lady Bird (Betsy Aidem); Hubert Humphrey (Robert Petkoff), who would later become his Vice-President; the veteran Southern senator Richard Russell (John McMartin), one of his closest colleagues; his arch-rival, Governor George Wallace (Rob Campbell); FBI director J. Edgar Hoover (Michael McKean) and such civil rights leaders as Martin Luther King, Jr. (Brandon J. Dirden), Ralph Abernathy (J. Bernard Calloway) and Stokely Carmichael (William Jackson), among many others.

The playwright, who won the Pulitzer Prize for his The Kentucky Cycle, is no stranger to large-scale historical drama, and he conveys the complicated tale with assured skill. The characterizations and sharply written dialogue ring true, and the complex political maneuverings are rendered with an uncommon clarity, abetted by Shawn Sagady’s projections featuring archival film footage and helpful identifications of many of the supporting characters.

But despite its admirable ambitions the play never quite manages to be sufficiently compelling, lacking the theatrical power to elevate it above the level of an informative history lesson. That it works to the extent that it does is largely due to Cranston’s compelling performance. The actor, looking uncannily like Johnson with the aid of unobtrusive prosthetics and affecting a convincing Texan accent, superbly depicts the master politician’s wily intelligence and blustering personality as well as the tragic personality flaws that would ultimately undermine his presidency.

Under Bill Rauch’s cohesive direction, the large ensemble, many of them playing multiple roles, delivers mostly fine support, with the exceptions being Dirden, who fails to convey King’s charismatic magnetism, and McKean, miscast as the menacing Hoover.

It’s not surprising that this large-scaled play with its massive cast would be presented in the Neil Simon Theatre, normally a musical house. But commercial considerations aside, it would be far more effective in a more intimate venue. Christopher Acebo’s stark set, composed largely of semi-circular wooden benches, fails to impress, and such theatrical touches as having confetti rain down on the audience in celebration of Johnson’s electoral victory seem pro forma.

But for all its flaws, All the Way is to be commended for its intelligence and ambition. Such serious dramas, especially those with large casts, are a rarity on Broadway these days. Credit must no doubt go to Cranston’s star power, and the talented actor doesn’t disappoint. His bravura performance, sure to be recognized come awards time, registers as a highlight of the theater season thus far.

Neil Simon Theatre, 250 W. 52nd St. 800-745-3000. www.Ticketmaster.com. Through June 24.

Review: The Bridges of Madison County

Feb 21st

Kelli O'Hara and Steven Pasquale in The Bridges of MadisonCounty

(©Joan Marcus)

Is it too much to ask of a show called The Bridges of Madison County that we actually see one of the covered bridges that provide its title?

Sure, Michael Yeargan’s set design dutifully represents one of the archetypal structures with a series of arches. But much like this simultaneously intimate and overblown musical adapted from Robert James Waller’s gazillion-selling 1992 novel, it feels woefully inadequate.

Millions of people, probably most of them middle-aged women, swooned to the literary source material which was also made into a 1995 film directed by and starring Clint Eastwood, with Meryl Streep in the role of Francesca, the Italian war bride who has long settled into a boring marriage with an Iowa farmer.

This musical version featuring a score by Jason Robert Brown (The Last Five Years, Parade) and book by Marsha Norman (‘night Mother, The Color Purple) is no doubt aiming for a similar demographic. But from the plaintive sound of a cello in its opening moments to its ghostly reunion between the ill-fated lovers at the end, it strikes nary an unpredictable note.

The show directed by Bartlett Sher, first seen at the Williamstown Theatre Festival, concerns the fateful meeting between Francesca (Kelli O’Hara), married for eighteen years to the inattentive Bud (Hunter Foster), and Robert Kinkaid (Stephen Pasquale), a ruggedly handsome National Geographic photographer who has arrived in the flatlands of Iowa to photograph its celebrated covered bridges. One day Robert literally shows up on her doorstep, with Francesca, whose husband and two children have left for several days to attend a state fair, eagerly welcoming him in.

It doesn’t take long for Francesca and Robert, fueled by a bottle of brandy and some tender slow-dancing to the radio, to embark on a torrid affair that reawakens passionate nature that has been smothered by years of household drudgery. Lying to her husband Bud (Hunter Foster) and evading the suspicions of her busybody and rather jealous neighbor Marge (Cass Morgan), Francesca begins to seriously contemplate Robert’s offer to run away with him and share his wanderlust.

The schematic storyline was given great resonance in Eastwood’s subtle film adaptation. But there’s little subtlety in this show which hammers home its romantic themes in oppressive fashion. Brown’s score which aspires to operatic heights with its assemblage of soaring aria-like ballads is lush and melodic. But it eventually wears you down with its overly heightened emotionalism that is only partially alleviated by a country-flavored numbers.

Norman strains the simple storyline with a surfeit of extraneous characters and situations, including subplots involving the relationship between Marge and her common-sense spouting husband Charlie (Michael X. Martin) and endless segues to Francesca’s family at the state fair and the sibling rivalry between her daughter Carolyn (Caitlin Kinnunen) and son Michael (Derek Klena). Most egregiously, the main action is followed by a lengthy melodramatic coda filling us in on the two principal characters’ lives after their four day encounter. What might have made for an affecting 90-minute chamber musical is here stretched out to a numbingly bloated two hours and forty minutes.

Sher’s staging is also overly fussy, with scenery constantly being wheeled back and forth and the minor characters observing the action as if they were audience members who were mistakenly assigned onstage seats.

O’Hara (affecting a reasonably convincing Italian accent) and Pasquale make for an attractive couple, and their chemistry—they also co-starred in the off-Broadway musical Far From Heaven—is palpable. Both deliver strong, affecting performances that are enhanced by their superb vocalizing of the demanding score, including a second act ballad, “One Second and a Million Miles,” which justifiably stops the show. Strong contributions are also made by Foster, who provides unexpected shadings to his potentially stereotypical role, and Morgan, very amusing as the overly curious neighbor.

But for all its blatant attempts to tug at the heartstrings, The Bridges of Madison Country remains curiously unmoving. It’s as if its creators assumed that the source material was so potent in its melodramatic themes that all they had to do was accentuate them. But sometimes less is more.

Gerald Schoenfeld Theatre, 236 W. 45th St. 212-239-6200. www.Telecharge.com.

Review: Outside Mullingar

Jan 24th

Brian F. O'Byrne and Debra Messing in Outside Mulllingar

(©Joan Marcus)

Playwright John Patrick Shanley pours on the Irish blarney in Outside Mullingar, which strains mightily for Moonstruck-style whimsy but mainly falls flat. This shaggy dog romantic comedy receiving its world premiere courtesy of the Manhattan Theatre Club mainly sputters along to little effect until its climactic scene, which is both undeniably charming and mind-bogglingly silly.

Debra Messing of (TV’s Will and Grace, Smash) makes her Broadway debut here and is faced with the daunting task of affecting a Gaelic accent opposite her genuinely Irish co-stars Brian F. O’Byrne, Peter Maloney and Dearbhla Molloy. She only partially succeeds, but her luminous presence and sharp line readings overcome any linguistic difficulties.

The plot concerns single fortysomethings Anthony (O’Byrne) and Rosemary (Messing), both tending to elderly single parents while living in adjoining farms in the Irish countryside. It’s quickly evident that the chain-smoking, sardonic Rosemary has long harbored romantic feelings towards her neighbor, but Anthony, who has spent his adult years pining for a former childhood sweetheart, is oblivious.

Much of the 95-minute play’s running time is boringly concerned with a long-lasting feud between the two families, which has something to do with Anthony’s father Tony (Maloney) having once sold a right-of-way passage to his property to Rosemary’s father and now widowed mother (Molloy).

With the exception of an emotional late-night scene between Anthony and his dying father, the play mainly rambles, its discursive dialogue often unintelligible because of the thick accents. Things finally come to a head in the lengthy final scene, in which Anthony and Rosemary amusingly and movingly stumble their way towards redefining their relationship. Unfortunately, the ultimate revelation for the reason behind Anthony’s emotional withdrawal is so jaw-droppingly silly that it makes us wonder what the hell Shanley was thinking.

Director Doug Hughes, who had a far more successful collaboration with the playwright on the Tony Award-winning Doubt, is unable to bring much life to the strained proceedings, while the rustic sets and costumes, by John Lee Beatty and Catherine Zuber respectively, provide the proper Irish atmosphere.

The performances, at least, make it somewhat bearable, with Maloney and Molloy injecting sly moments of humor into their portrayals. Messing, seemingly channeling Maureen O’Hara, brings a winning charm to the feisty Rosemary, and O’Byrne expertly manages to make Anthony’s cluelessness both moving and endearing.

It’s nice to see Shanley attempting to return to his Irish roots. It’s too bad, then, that he seems to have taken a wrong turn getting there.

Samuel J. Friedman Theatre, 261 W. 47th St. 212-239-6200. www.Telecharge.com. Through March 16.

Review: Machinal

Jan 17th

Rebecca Hall (foreground) with Jason Loughlin and Ryan Dinning (background) in Machinal

(©Joan Marcus)

The Roundabout Theatre Company’s current revival of Sophie Treadwell’s classic 1928 Expressionist drama Machinal represents a marked departure from this non-profit theater’s usual staid diet of Shaw and drawing room comedies. Featuring a galvanizing staging by up-and-coming British director Lyndsey Tuner and a striking scenic design Es Devlin, this production starring Rebecca Hall breathes new life into this rarely seen curiosity piece.

Inspired by the true story of Ruth Synder--who was executed for killing her husband and whose electric chair photo famously made the front page of the Daily News--the play is sometimes off-putting in its stylized language and stilted dramaturgy. But it fascinates nonetheless, both as an example of its dated theatrical style and its still powerful portrait of a hapless young woman victimized by an oppressive society.

Composed of nine “episodes,” the play depicts the ill-fated marriage between a “Young Woman” (Hall) and her boss (Michael Cumpsty) at the company where she works as a stenographer. When first seen, Helen, as she is referred to in the script, is frantically fleeing the cramped confines of an overcrowded subway car, and it soon becomes clear that this is merely the first example of her lack of coping abilities.

Subsequent episodes depict her strained relations with her co-workers and her endlessly nagging mother (Suzanne Bertish); her awkward honeymoon with her patronizing, overbearing new husband; her giving birth to an unwanted child; and her meeting with a sexy man (Morgan Spector, in the role originally played by a young Clark Gable) with whom she has a rapturous one-night stand. It’s only in the latter scene in which Helen seems to come to thrillingly vibrant life, giggling and acting like a giddy teenager when she previously seemed to wander through life in a dazed stupor.

This sexual awakening prompts her to brutally murder her husband, and she is quickly put on trial and sentenced to death. The play ends with her strapped in the electric chair, as a sudden bright light signals the switch being pulled.

The work is difficult to take at times, with its clipped, staccato dialogue and a stream-of-consciousness monologue that seems to go on forever. But its strengths are superbly realized in this suitably stylized production featuring a dazzling series of sets constantly shifting on the revolving turntable stage.

At first, Hall seems somewhat miscast in the lead role, with her striking beauty and amazon-like physique at odds with her character’s mousy demeanor and victim-like status. But her deeply committed performance eventually overcomes any reservations, and indeed makes Helen’s fate seem all the more tragic.

The ever-reliable Cumpsty and the physically imposing Spector offer excellent support as the central male characters; Bertish well conveys the mother’s grating qualities; and the large ensemble fills their multiple roles with skillful precision.

It was a gutsy move for this traditionally conservative theater company to put on this audacious production of such a challenging work. Fortunately for them and their audiences, that risk has been amply rewarded.

American Airlines Theatre, 227 W. 42nd St. 212-719-1300. www.roundabouttheatre.org. Through March 2.