Category: "Broadway"

Review: Clybourne Park

Apr 20th

Its Pulitzer Prize not withstanding, Clybourne Park still seems to me a better idea for a play than it actually is. Bruce Norris’ dark comedy, which has now arrived on Broadway after heralded engagements at Playwrights Horizons and numerous other venues, certainly earns points for pungently tackling the still white-hot issue of racism. But this riff on Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun substitutes gimmickry for real drama and ultimately feels more sensationalistic than enlightening.

The premise is certainly imaginative. The first half is set in 1959, when a white Chicago couple is preparing to sell their home to a black family—the Youngers of Hansberry’s drama, although it’s never explicitly spelled out. The sale has their white neighbors, led by a smarmy community spokesman, up in arms.

Act 2 takes place 50 years later, when the dilapidated dwelling in the now gentrifying neighborhood has just been bought by a yuppie couple. The angry interactions among the characters in both acts illustrate the racial divides that are still prevalent, if now somewhat beneath the surface.

The first segment features generous doses of mordant humor, mostly supplied by the angry homeowner (Frank Wood) who bristles at the interference of such characters as an unctuous priest (Brendan Griffin). But melodrama comes to the fore with the revelation that the long-married couple is selling their home because their son, who was accused of committing an atrocity during his service in the Korean War, hanged himself in an upstairs bedroom.

In the play’s second half the humor takes a darker turn, as the characters, including a black couple, begin trading provocative racial jokes and insults that recall the plays of Neil LaBute in their deliberate shock value. The not so subtle message is that even white liberals harbor unconscious, latent prejudices. The two halves of the play are tied together in a coda that is meant to be hauntingly poetic but doesn’t really mean very much.

The playwright has a clear knack for pungent comic dialogue, as previously displayed in such equally edgy works as The Pain and the Itch. But there’s a glib self-satisfaction and neatness to this play that prevents it from being as revelatory as it clearly intends.

The evening glides by entertainingly enough thanks to the sharp-as-nails staging by Pam MacKinnon and the virtuosic performances by the ensemble, all playing double roles. Each performer shines in at least one if not both of them, especially Jeremy Shamos as the yuppie who keeps putting his foot in his mouth; Crystal A. Dickinson as a long-suffering black maid and later as the friend who delivers a joke shocking enough to make David Mamet blush; and especially Wood as the father whose sharp anger masks his underlying sorrow.

Hansberry’s Raisin in the Sun has endured for more than a half-century because it depicted the travails of fully dimensional characters even as delved into the social issues of its time. Clybourne Park, for all its provocations, is unlikely to have an equally long shelf life.

Walter Kerr Theatre, 219 W. 48th St. 212-239-6200. www.telecharge.com.

Review: One Man, Two Guvnors

Apr 18th

With the notable exception of Noises Off, theatrical farce is far more often labored than amusing. But One Man, Two Guvnors, newly arrived on Broadway from London’s West End, is hilarious enough to melt the most stone-faced. Featuring a star-making turn by James Corden in what may be the single most endearingly funny performance I’ve ever seen onstage, this updating of Carlo Goldoni’s 18th century commedia dell’ arte masterpiece offers two-and-a-half blissful hours of escapism.

Playwright Richard Bean has cleverly transposed the action to 1963 Brighton, providing the opportunity for plenty of visual gags riffing on the era’s mod stylings, as well as musical contributions from an onstage four-piece skiffle band dubbed “The Craze.”

The plot is too convoluted to explain in detail, but it’s basically an excuse for a non-stop series of throwaway gags anyway. Suffice it to say that it involves the portly Frances Henshall (Corden, last seen here in The History Boys), who somehow winds up becoming the underling to both a pretentious public-schooled gangster (Oliver Chris) and a small-time criminal (Jemima Rooper). Except that the latter is actually the criminal’s twin sister, who has donned male drag to impersonate him and avenge his murder by the gangster.

The evening’s unquestionable highlight is an extended scene in which the ever-ravenous Frances attempts to stuff his face while simultaneously attending to the culinary needs of his two bosses who are dining in separate rooms at the local pub. Most of the hilarity is provided by the physical contortions of an octogenarian waiter with a heart condition, brilliantly played by the rubber-limbed Tom Edden.

Admittedly, the humor drags at times, especially in the second act in which all the plot elements have to be neatly tied together. But there are so many jokes, of both the visual and verbal variety, that one can easily forgive any longueurs.

Corden, resplendently attired in plaid, offers a virtuosic turn in which every moment feels off-the-cuff and improvised. And some of it is, as many of the bigger laughs come from his interactions with hapless audience members--the surprises of which, and they are many, will not be revealed here. The actor has been playing the role since the production’s National Theatre premiere a year ago, but there is no staleness evident. Indeed, the sheer joy he exudes in being onstage is contagious.

Nicholas Hytner--with the clearly invaluable aid of “physical comedy director” Cal McCrystal--has staged the comic proceedings with Swiss watch-style precision. The performances by the entire ensemble, including the band members who provide diverting musical interludes, are exceptional, although the wonderfully named Suzie Toase is a particular delight as the voluptuous wench who makes Francis an unlikely sex object.

Music Box Theatre, 239 W. 45th St. 212-239-6200. www.Telecharge.com.

Review: Evita

Apr 13th

“Tasteful” is not a word that springs to mind when thinking about Eva Peron, and it shouldn’t when it comes to Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice’s musical Evita either. But that’s exactly the quality that best describes the new Broadway revival, the first since the work’s premiere. Understated and underwhelming, it sacrifices the original’s bombast and flash for a substance that isn’t really there. Hal Prince’s now legendary 1979 production certainly had its flaws, but being boring wasn’t one of them.

This version staged by Michael Grandage and first seen on the West End in 2006 begins with somber film footage of Eva’s coffin being paraded through the streets of Buenos Aires, and the funereal tone never wavers from there.

Argentine actress Elena Rogers makes her Broadway debut in the title role, and it is not an unalloyed triumph. The Olivier-Award winning performer, who garnered raves for her London portrayal, lacks the charisma, or “star quality,” as the show puts it, to fully convince as the galvanizing Evita. She’s credible in dramatic terms, and more than credible when it comes to the dancing. But her singing becomes shrill and grating in her higher register, and she doesn’t have the pipes to do justice to a song like “Don’t Cry for Me, Argentina.”

Pop star Ricky Martin is the clear box-office draw here. But unlike the original’s Mandy Patinkin, who infused his every number with a biting sarcasm, his charming but uncharismatic Che seems more irritated than outraged. Not surprisingly, the singer handles the vocals with ease and, much to the delight of his female fans, he engages in some vigorously sexy dancing. In this version, the character is an everyman rather than the Che Guevara of Prince’s staging, but while that interpolation didn’t make any particular sense, it did add a historical frisson that is lacking here.

Also disappointing is Michael Cerveris as Peron. The normally compelling actor makes surprisingly little impact, although he does bring a suave sexiness to the role.

Grandage’s pageant-like staging of the sung-through piece moves well enough, and Rob Ashford’s tango-influenced choreography provides plenty of eye candy. But the main appeal of this show is its score--featuring such classic numbers as “Oh What a Circus,” “A New Argentina,” “Buenos Aires” and others—and it doesn’t come across with much impact with this version’s tinny orchestrations and wan singing. And the addition of “You Must Love Me,” written for the unfortunate 1996 film version starring Madonna, doesn’t help much.

Marquis Theatre, 1535 Broadway. 800-745-3000. www.ticketmaster.com.

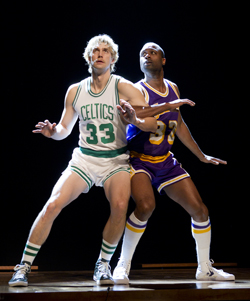

Review: Magic/Bird

Apr 12th

If you’re going to write a play about two legendary sports figures it would help if more than one of them was interesting. Such is the dilemma of Eric Simonson’s second attempt to lure reluctant middle-aged men to Broadway. But unlike last season’s Lombardi, which presented a compelling portrait of a truly larger-than-life figure, Magic/Bird has a central emptiness at its core.

The play concerns the basketball players Larry Bird and Earvin “Magic” Johnson, whose professional rivalry and complicated personal relationship fascinated sports fans during the 1980s. Adding innate drama to the story, of course, is Johnson’s 1991 announcement that he is HIV-positive.

That powerful scene opens the play, which relates its story in flashback form. The evening certainly covers all the bases—sorry, wrong sports metaphor—in its depiction of, among other things, the several championship games fought between the Lakers and the Celtics; the friendship that resulted when a reluctant Johnson traveled at Bird’s insistence to his home town of French Lick, Indiana to film a now-classic Converse commercial; and their playing together in the 1992 Olympics in what became known as the “Dream Team.”

Bird was notorious for being an anti-social and uncommunicative figure, which the play captures all too well. Although the character’s loquaciousness provides some comic mileage, a little goes a long way and it ultimately becomes simply boring.

Although physically suitable for their roles and displaying some impressive hoops chops, Kevin Daniels and Tug Coker are underwhelming as Magic and Bird respectively. Daniels delivers an ingratiating performance, but is understandably at a loss to convey Magic’s megawatt charisma. And Coker is unable to make Bird’s recessive nature sufficiently intriguing.

Far better are the supporting players in their multiple roles. Peter Scolari entertainingly essays such famous coaches as Red Auerbach and Pat Riley; Deirdre O’Connell is a hoot as Bird’s mother, who hosts Magic for lunch in the evening’s most entertaining scene; and Francois Battiste gets laughs every time he imitates Bryant Gumbel’s distinctive high-pitched voice.

The staging by Thomas Kail features some clever touches, such as introducing the cast in sports-team style at the play’s beginning and the use of real-life footage to complement the onstage action. And the period atmosphere is appropriately with songs by the likes of Blondie and Huey Lewis and the News.

Magic/Bird is being presented in association with the NBA, which should certainly help it in terms of cross-promotional branding. And since non-basketball fans are likely to be left cold by this wan drama, it will need all the help it can get.

Longacre Theatre, 220 W. 48th St. 212-239-6200. www.telecharge.com.

Review: End of the Rainbow

Apr 3rd

It may be time to let Judy Garland rest in peace. The beloved entertainer has been a never-ending subject of fascination since her untimely death. Since then, she’s been portrayed on stage, film and a seemingly endless series of cabaret acts. The latest example of this biographical necrophilia is End of the Rainbow, a London import starring Tracie Bennett that has just opened for a Broadway run.

Peter Quilter’s musical drama, staged by Terry Johnson, is set in December, 1968, just a few months before Garland died. It takes place at London’s Ritz Hotel, where the entertainer is preparing for a series of nightclub concerts that was intended to be yet another comeback.

She’s accompanied by her fifth and much younger husband Mickey Deans (Tom Pelphrey), who is managing her career while attempting to keep her away from the booze and pills that are hastening her decline. Offering moral support is Anthony (a fine Michael Cumpsty), her deeply devoted, longtime pianist.

The portrait of Garland that the play paints is a by now familiar one. She cracks ribald jokes; curses like a longshoreman; and throws temper tantrums whenever she’s feeling deprived of the substances with which she’s been self-medicating for years.

Oh, and she sings. The rear wall of the lavish hotel room periodically disappears to reveal a five-piece band as Bennett bursts into such signature Garland numbers as “The Man That Got Away,” “Come Rain or Come Shine” and, of course, “Over the Rainbow.”

The Olivier Award-winning won well deserved acclaim across the pond for her performance. She bears a certain resemblance both physically and vocally to Garland—the singer’s late career hairstyle and onstage costuming have been faithfully recreated—and she inhabits Garland’s neurotic, wickedly funny personality in fully convincing fashion. It’s a bravura turn, even if the sheer number of Garland impersonators that have come along in the last few decades inevitably reduces it of some of its freshness.

Unfortunately, the evening’s one-note nature defeats her best efforts. Repetitive and plodding, the play feels like little more than an extended, morbid vignette interrupted by songs we’ve heard many times before. It ultimately reduces rather than sheds light on this complex personality and show business legend.

Belasco Theatre, 111 W. 44th St. 212-239-6200. www.telecharge.com.