Category: "Off-Broadway"

Review: What's It All About? Bacharach Reimagined

Dec 6th

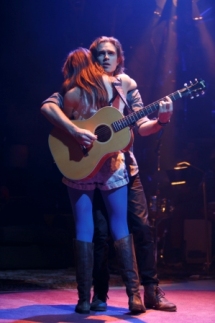

Kyle Riabko and Laura Dreyfuss in What’s It All About? Bacharach Reimagined

(©Eric Ray Davidson)

Don’t expect brassy horns or Dionne Warwick-style belting in What’s It All About? Bacharach Reimagined, the accurately titled new musical revue celebrating the work of the legendary pop composer. This show featuring some two dozen pop classics indeed reinterprets them in startling fashion, presenting the material in a rhythmic, indie rock style a la such performers as Bon Iver and Sufjan Stevens. But while the stripped-down approach to the songs is certainly original, it also has the unfortunate effect of draining the life out of most of them.

Opinions will no doubt be sharply divided on the show co-conceived by Kyle Riabko and David Lane Seltzer, with the former also serving as performer and musical arranger. Being a huge Bacharach fan myself, I’m not necessarily averse to hearing his music performed in a different style. But the seven- member ensemble deliver nearly every number in the same low-key, sincere manner that ultimately proves simply monotonous.

The beauty of the melodies of such songs as “This Guy’s in Love With You,” “The Look of Love,” “Close to You” and so many others still shines brightly, as do the lyrics by Bacharach’s longtime collaborator Hal David and several others. But the overly solemn delivery feels dirge-like, giving the staged concert the feel of a memorial service rather than a celebration. And the youthfulness of the performers and overall preciousness of the staging make it resemble a very special episode of Glee.

Riabko starts off the evening solo, with a heartfelt introduction and the playing of an inconsequential message left on his answering machine by the composer himself. Playing guitar and singing in a sweet tenor voice, he comes across as a lightweight, with the rest of the performers—Daniel Bailen, Laura Dreyfuss, James Nathan Hopkins, Nathaly Lopez, James Williams and Daniel Woods, many of them doubling as instrumentalists--making a similarly underwhelming impression.

The songs are often presented in mashed-up, medley form, mostly to their detriment. Verses of one number bleed into another, giving them the feel of snippets. Director Steve Hoggett (Once, American Idiot) seems intent on compensating for the lack of musical spark by employing constant bits of silly stage business. During “Walk on By,” the performers solemnly arrange chairs onto a circular platform in the center of the stage, which mainly serves to reference the opening lyrics of the next number, “A House is Not a Home” (“A chair is still a chair).” For “Make It Easy on Yourself,” the performers revolve on the spinning platform for an apparent reason whatsoever.

Adding to the overall Williamsburg hipster vibe is the extravagant set design by Christine Jones and Brett J. Banakis featuring large rugs and countless antique lamps. Sofas in several corners of the stage accommodate not only the performers but also several audience members who seem pleased by the close proximity. Japhy Weideman’s overly busy lighting design tries too hard to be in synch with the music, while the choreography seems all too similar to Hoggett’s work on Once.

To be fair, there are some outstanding moments, such as Lopez’ slow, soulful take on “Don’t Make Me Over” and Dreyfuss’ equally affecting “Walk on By.” In general, the solo numbers are more effective than the group ones which suffer from excessive busyness.

By the end of the 90-minute evening, the net effect is more enervating than exhilarating, not a quality one would normally associate with Bacharach’s buoyant music. The only moment of pure fun comes with the encore, “What’s New, Pussycat,” no doubt chosen because it’s virtually impossible to deliver it in serious fashion.

The endless eagerness to please is reinforced by yet another cutesy gimmick. Leaving the theater, the audience is greeted by the performers who have already rushed outside to serenade us with “Raindrops Keep Fallin’ on My Head.” Fortunately for both them and us, it was a blissfully clear night.

New York Theatre Workshop, 79 E. 4th St. 212-279-4200. www.ticketcentral.com. Through Jan. 5.

Review: Not by Bread Alone

Jan 24th

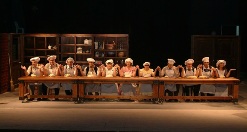

If the performers onstage at NYU’s Skirball Center seem to be in their own world, that’s because they really are. They’re the members of Israel’s Nalaga’at Theater, and they’re all, to varying degrees, both deaf and blind. But that doesn’t stop them from fully expressing themselves in their beautifully heartfelt production, Not by Bread Alone.

Conceived and directed by Adina Tal, the evening is a collection of vignettes and skits, some poignant, some farcical, in which the cast members convey what it’s like to live in their sensory-deprived world. Their words are communicated via supertitles and translators; they’re gently guided around the stage by a crew of black-clad handlers; and they receive their cues via the pounding of drums from which they sense the vibrations.

As we enter the theater the eleven performers are already visible, seated at a long table and busily kneading dough which is eventually placed in several onstage ovens. As the show proceeds, the pleasant aroma of baking bread permeates the auditorium, but thankfully it’s no tease. At the conclusion the audience is invited to literally break bread with the performers onstage, in an affirmation of the communal bond that’s been formed.

The piece is most effective at its simplest. An older woman touchingly describes the despair she felt upon the realization that she’ll never see the face of her grandson. Another relates how important it is for him to shake the hand of a person he’s meeting, just as proof that they really exist. Several relate the history of their condition, and whether or not they have any memories of sights or sounds.

The attempts at clowning and visual comedy are less successful, with vaudeville-style sketches depicting such events as a visit to a hairdresser, an Italian vacation and a wedding having a forced, strained quality that’s in marked contrast to the naked honesty evidenced by the performers while simply telling their own stories.

To fully immerse yourself in the experience, you’ll want to shell out for the admittedly pricey ($200) show and dinner package. The company has imported two signature elements from its home theater in Tel Aviv: the Café Kapish, featuring deaf servers, in which orders are taken only via sign language; and the BlackOut restaurant. In the latter, you’re served a three-course meal in complete darkness by blind waiters who use bells to communicate their movements. The dishes created by famed NYC restaurateur Danny Meyer (Union Square Café, Gramercy Tavern) feature a wide array of tastes and textures which must be discerned without the usual visual accompaniment. For an hour at least, you’ll at least have a partial idea of the world these performers inhabit every day of their lives.

Skirball Center for the Performing Arts, 566 LaGuardia Place. 212-352-3101. www.nyuskirball.org. Through Feb. 3.

Review: Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike

Nov 13th

Christopher Durang’s Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike manages the neat trick of being both a sometimes uproarious send-up of Chekhov and an affectionately heartwarming modern-day variation on his themes. Featuring a stellar cast of such comedic pros as David Hyde Pierce, Kristine Nielsen and Sigourney Weaver, the overlong play overstays its welcome but provides plenty of hilarious moments along the way.

Set at a farmhouse in present-day Bucks County, Pennsylvania, the play first introduces us to siblings Vanya (Pierce) and Sonia (Nielsen), their names given to them by professor parents enamored of Chekhov. The middle-aged Vanya and spinster Sonia live a comfortable life, thanks to the largesse of their successful actress sister Masha (Weaver), who unexpectedly shows up for a surprise visit.

The occasion is a costume party being held by one of her friends at a nearby house formerly owned by Dorothy Parker. Masha, intending to go dressed as Snow White, is happy to invite her siblings along, provided they complement her costume by dressing as two of the dwarves, specifically Grumpy and Dopey.

The endlessly self-absorbed, vainglorious Masha has arrived with Spike (Billy Magnussen), her much younger boyfriend, in tow. An underemployed actor whose biggest claim to fame was nearly getting a part in HBO’s Entourage 2, the equally vapid if hunky Spike has no compunction about stripping down to his underwear to take a quick dip in a nearby pond. There he encounters the sweet young Nina (Genevieve Angelson), who the insecure Masha immediately perceives as a threat.

Also on hand is Vanya and Sonia’s sassy housecleaner Cassandra (Shalita Grant), who lives up to her Greek mythology name by revealing soothsaying powers, not to mention a sideline in voodoo.

Durang’s gift for sharp comic dialogue and well-calibrated gags is well on display here, with the priceless interactions among the eccentric characters providing a steady stream of laughs. But the play strains in its allusions to Chekhov—Vanya and Sonia find their cushy lifestyle threatened by Masha’s announcement that she plans on selling the house, with a wan cherry orchard nearby—and the humor begins to wear thin, especially with several of the principals registering as little more than caricatures.

There are two wonderful scenes in the second act that are well worth the price of admission. Nielsen is brilliant in an alternately poignant and hilarious phone one-sided phone conversation in which Sonia hesitatingly agrees to a date with a man she’s met at the party. And Pierce delivers a tour-de-force comic turn with Vanya’s hysterical tirade about the lack of values and common decency in today’s society compared to when he was growing up in the 1950s.

Featuring a gloriously lavish set by David Korins and hilariously spot-on costumes by Emily Rebholz—Weaver’s Snow White costume is a hoot, as is Magnussen pastel-colored, skin-tight jeans—the production is expertly staged by Durang veteran Nicholas Martin (Betty’s Summer Vacation). The three lead performers are longtime collaborators of the playwright as well, which no doubt accounts for the relaxed comfort with which they fit into their comic roles.

Mitzi E. Newhouse Theater, 150 W. 65th St. 212-239-6200. www.lct.org.

Review: If There Is I Haven't Found It Yet

Sep 21st

Uneasily blending an examination into the global effects of climate change with dysfunctional family drama, British playwright Nick Payne’s dark comedy If There Is I Haven’t Found It Yet hasn’t quite found its footing in its American premiere by the Roundabout Theatre Company. One can only imagine the befuddled reactions the play will induce among the many young female fans of Jake Gyllenhaal, here making his New York stage debut.

The heartthrob actor plays Terry, the unkempt, slacker uncle of obese fifteen-year-old Anna (Annie Funke). Arriving for an unexpected family visit, Terry quick ingratiates himself to the troubled teen even if he proves ultimately ill-equipped to solve her myriad emotional problems.

Proving equally unhelpful to the oft-bullied girl are her parents. Her father George (Brian F. O’Byrne) is a writer/activist endlessly distracted by the book he’s working on about the devastating results of global warming, while her mother Fiona (Michelle Gomez) is a teacher who has transferred Annie to the school in which she teaches in a misguided attempt to protect her.

At first glance Terry would seem to be little help as well. Verbally maladroit except for his constant use of profanity, he’s also still deeply torn up over a recent break-up. But the friendship and attention he provides his niece at first seems to prop her up, albeit with the unintentional effect of awakening a sexual desire for her uncle.

The dramatically thin family dynamics on display are gussied up with a stylized staging by director Michael Longhurst. The stage is separated from the audience by a large moat, with the actors periodically flinging pieces of scenery into the water to ever lessening effect. And a climactic coup de theatre, while visually stunning, doesn’t justify the enormous trouble and expense it must have taken to produce it.

Gyllenhaal delivers an ingratiating turn as the prodigal uncle, and displays a convincing Cockney accent to boot. Funke is highly impressive as the body and soul-baring Anna, and O’Byrne and Gomez do the best with their underwritten roles. But despite their efforts, the evening still feels diffuse. If there any deeper meanings to be gleaned from this earnest drama, I haven’t found them yet.

Laura Pels Theatre at the Harold and Miriam Steinberg Center for Theatre, 111 W. 46th St. 212-719-1300. www.roundabouttheater.org. Through Nov. 25.

Review: Backbeat

Aug 14th

Now playing in Toronto by way of Glasgow and London’s West End—and prior to a hoped-for Broadway run—Backbeat: The Birth of the Beatles is far from the cheery juke-box musical one might expect. Concentrating on the tragic story of Stu Sutcliffe, the band’s original bassist who left the group to pursue an art career only to die from a brain hemorrhage at the age of 21, this musical adapted from the 1994 film is something of a downer despite the joyful rock music on display.

Still, there’s much here to admire, especially the profusion of meticulously recreated musical performances of the band’s original repertoire. The show concentrates on their early years, especially their residency at Hamburg’s seedy Kaiserkeller club, so expect to hear exuberant renditions of such classic rock and pop songs as “Johnny B. Goode,” “Long Tall Sally,” “A Taste of Honey” and “You Really Got a Hold on Me.”

The principal focus is on Sutcliffe (Nick Blood), who could barely play his instrument and was recruited into the band primarily because of his brooding, James Dean-style good looks and extremely close friendship with John Lennon (Andrew Knott). Although much has since been made of the exact nature of the relationship between the two similarly rebellious young men, the show handles it in a veiled, oblique fashion that proves dramatically unsatisfying.

Equally frustrating is the depiction of the central love affair between Sutcliffe and Astrid Kirchherr (Isabella Calthorpe), the beautiful young German photographer who eventually persuaded him to leave the band and follow his artistic dreams, but not before being instrumental in creating their distinctive mop-top hairstyles. As portrayed here, the two essentially peripheral figures are simply not that interesting.

Fortunately, the material’s dramatic deficiencies are compensated for by the terrific musical numbers, with the actors playing their own instruments as well as singing. The talented perfomers,, mostly imported from the original production, effectively convey the sheer joy these young men felt in their transformation from a skiffle cover band to pop music icons.

Accentuating the thinness of the main storyline is the fact the most effective scene in the show--adapted for the stage by the film’s director Iain Softley and playwright Stephen Jeffreys (The Libertine)--occurs during a lull in the action when Lennon and McCartney (Daniel Healy) are seen writing “Love Me Do.” Their beautifully written exchange perfectly conveys the contrasting artistic and personal styles that would eventually form one of the most fruitful collaborations in music history.

Other effective moments come when the band’s ambitious producer George Martin (James Wallace) fires the devastated original drummer, Pete Best (Oliver Bennett) and especially when Astrid photographs the band members. Those now iconic pictures are projected on a large screen in a wonderfully nostalgic montage that breathtakingly conveys her subjects’ photogenic charisma.

Veteran David Leveaux has staged the proceedings in admirably fluid fashion, with the action shifting back and forth between London, Hamburg and Liverpool. The show ends with a rather obvious effort to send audiences out on a high note, with an encore featuring performances of more Beatles classics that feels all too similar to the “megamixes” that have become a tired theatrical staple of pop music-themed musicals.

Royal Alexandra Theatre, 260 King St. West, Toronto, Canada. 416-872-1212. www.mirvish.com. Through Sept. 2.