Category: "Off-Broadway"

Review: Now.Here.This.

Mar 29th

Those impish wags from [title of show] are back to their meta-theatrical tricks in their new, similarly whimsically titled new musical. Starring Hunter Bell, Susan Blackwell, Heidi Blickenstaff and Jeff Bowen—all of whom collaborated on its development—Now.Here.This. demonstrates that this quartet haven’t lost their fascination with…themselves.

While their first show was all about its own creation, this effort is more personal, resembling a confessional musical therapy session. It’s loosely structured around an outing to the Museum of Natural History, which naturally gets the characters—Hunter, Susan, Heidi and Jeff, and you can probably guess who plays who—to thinking about…themselves.

This new work, which has a title inspired by a maxim by philosopher Thomas Merton, begins deceptively, with a song about the birth of the planet. But such cosmic concerns are soon abandoned, as the performers proceed to deliver comic riffs and musical numbers ostensibly inspired by the museum’s anthropological exhibits (“Did you know that a collective of turtles is called a ‘bale’ of turtles?”) but that really hinge on their personal lives. The details of which will not be forthcoming here, mostly because the utter triviality of the material tends to make it disappear quickly from memory. I do vaguely recall a lengthy discussion of the reason why Tootsie is the greatest American film comedy of all time, but that’s mainly because it made me want to exit the theater immediately and rent it.

The endless self-absorption on display can perhaps by best illustrated by the aptly titled number “Give Me Your Attention,” in which Blickenstaff sings of desperately trying to earn her family’s approval as a child. It’s time to get over it, already.

The performers try very, very hard to be engaging and likeable, and they sometimes manage to succeed in spite of themselves. Director/choreographer Michael Berresse has provided a suitably casual seeming staging, and some of the numbers, such as “Then Comes You,” are sweetly melodic. But there’s clearly something wrong when you leave a musical not humming the songs, but rather wishing you could hear more of Roger Rees’ mellifluous voice-overs.

Vineyard Theatre, 108 E. 15th St. 212-353-0303. www.vineyardtheatre.org.

Review: Regrets

Mar 28th

Rising British playwright Matt Charman reveals a fascination with the darker aspects of ‘50s era American society in Regrets, now receiving its world premiere from the Manhattan Theatre Club. But he’s gotten a little too ambitious here, dealing with two fascinating episodes when one would have been more than enough. The results feel at once overstuffed and undernourished.

The play is set in a ramshackle cabin retreat in 1954 Nevada where men can go to fulfill a six-week residency requirement to get quickie divorces. The newest and very atypical arrival is Caleb (Ansel Elgort), who is only 18-years-old and not very forthcoming about the circumstances that have brought him there.

The camp--overseen by Mrs. Duke (Adriane Lenox), an African-American woman who has strict rules and won’t take any gruff--is also the temporary home for the blustery Gerald (Lucas Caleb Rooney); the milquetoast Alvin (Richard Topol); and the apparent lifer Ben (Brian Hutchison) who’s been there for three years. A frequent visitor is Chrissie (Alexis Bledel, of TV’s Gilmore Girls), a young woman who has taken up prostitution to earn the money to get away from her abusive father. But while her steady customer Gerald dreams of running away with her, she’s developed a fixation on the gentle, well-read Ben.

This exotic milieu would seem to present plenty of potential for interesting plot and character dynamics, but the playwright takes things in a different direction. He also weaves the communist witch hunts taking place at the same time into the mix, via a menacing FBI agent (Curt Bouril) investigating one of the men for having Red ties.

The strained, unconvincing results seem indicative of a playwright who had a good idea, got distracted by another, and attempted to combine them to mostly unconvincing effect. It’s too bad, because the writing—featuring incisive characterizations and nastily funny dialogue—reveals definite talent.

Director Carolyn Cantor--aided by Rachel Hauck’s evocative set design and Ben Stanton’s lighting redolent of the Arizona desert--has provided a production that feels wholly authentic. The performances are for the most part equally lived-in, with particularly fine work by Lenox as the no-nonsense caretaker and Rooney, Topol and Hutchison as the older men who’ve lost their bearings.

NY City Center Stage I, 131 W. 55th St. 212-581-1212. www.nycitycenter.org. Through April 29.

Review: 'Tis Pity She's a Whore

Mar 26th

The last time I checked, incest between a brother and sister was still considered relatively abhorrent.

So it naturally comes as a surprise that the Cheek by Jowl production of John Ford’s 17th century tragedy ‘Tis Pity She’s a Whore feels compelled to ratchet up the shock value. Featuring enough male partial nudity to qualify as a Chippendale’s revue, Declan Donnelan’s fussy staging is filled with the sort of high-concept directorial touches that call attention to everything but, uh, the text.

Upon entering the BAM Harvey Theater, my heart sunk immediately upon sighting the set depicting a woman’s bedroom complete with blood-red bed and posters of Gone With the Wind, Breakfast at Tiffany’s and True Blood adorning the walls.

The room is inhabited by the young and sexy Annabella (Lydia Wilson), who is being ardently wooed by her love-struck brother Giovanni (Jack Gordon). When she succumbs to his advances—he’s hard to resist when he strips down to his black boxer-briefs—it results in the inevitable complications, including pregnancy. Even if you’re not familiar with the play, you can probably guess that things don’t turn out well. In the case of this particularly carnage-minded dramatist, it also means that internal organs will eventually be removed from their bodies.

You’d best be familiar with the convoluted plot before going in, because it’s rendered fairly incomprehensible here despite the elimination of several subplots and supporting characters that reduce the running time to a mere two hours.

From the opening interpretive dance accompanied by throbbing electronic music to the male characters’ endless stripping down to their underwear—don’t worry, the lissome Wilson frequently bares her body as well—to the absurd anachronisms, the production is consistently ridiculous. Worse, it constantly presents the meanings of the play rather than the play itself, as if not trusting modern audiences to grasp its essential truths.

The uneven acting is another problem, although the British ensemble handles the verse well. The only standout performances come from Suzanne Burden as the vengeful widow Hippolita and Lizzie Hopley as the all-seeing maid, Putana, although both actresses are forced to contend with some unfortunate costuming.

Another play by Ford, The Broken Heart, was presented earlier this season in a vividly stark, powerful production from Theater for a New Audience that proved that his works don’t need such gimmickry to resonate. Like that play, ‘Tis Pity is very rarely seen on our shores. ‘Tis pity, then, that this is the version we get.

Harvey Theater, Brooklyn Academy of Music, 651 Fulton St. 718-636-4100. www.bam.org. Through March 31.

Review: An Iliad

Mar 9th

The simple act of storytelling is a time-honored theatrical tradition. But it can also a hackneyed one. Case in point: An Iliad, the new one-man show—well, technically two man, but more on that later—based on the poem by Homer as translated by Robert Fagles. This epic tale of the Trojan War has been rendered into a chatty, meandering monologue delivered by a character only known as “The Poet.” He’s accompanied with music by an onstage bassist providing the appropriate emotional cues.

This piece being presented by the New York Theatre Workshop was adapted by actor Denis O’Hare and playwright Lisa Peterson (Light Shining in Buckinghamshire, Slavs), with the latter also directing. Theatergoers are being enticed to see the production not once but twice, since O’Hare is alternating in the role with Stephen Spinella.

Although I’m a dedicated theatergoer, even the prospect of comparing two such talented actors wasn’t enough to induce me to sit through the 100-minute monologue a second time. I chose to see O’Hare since he was also the co-author.

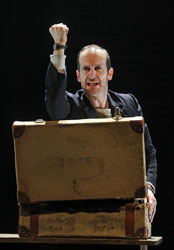

The actor, clad in a shabby overcoat and toting a suitcase, wanders onto the stage like a character in a Beckett play and begins chanting in Greek. But he quickly resorts to mostly colloquial language, providing an abridged version of the story that concentrates on the Greek warrior Achilles and his Trojan counterpart Hector.

Unless you’re familiar with the complicated story--much of which has admittedly slipped from my memory since college days—the proceedings are apt to prove somewhat confusing. But not to worry, since the message of the piece is, gasp, war is bad, and its continued relevance is hammered home in a recitation of a litany of modern-day conflicts.

The normally mesmerizing O’Hare recites the text in a world-weary monotone that quickly proves tedious. And although the expert lighting and sound design provide evocative underpinnings, they’re not enough to give the piece sufficient theatricality. For all its obvious good intentions, it ultimately has the feel of a self-indulgent stunt.

New York Theatre Workshop, 79 E. 4th St. 212-279-4200. www.ticketcentral.com. Through March 25.

Review: The Lady From Dubuque

Mar 7th

Not that I’m in any rush, but whenever death comes for me I hope it takes the form of the Lady from Dubuque.

As elegantly personified by Jane Alexander in the Signature Theatre’s revival of Edward Albee’s haunting play being presented under the possessory moniker of Edward Albee’s The Lady From Dubuque, death is a highly comforting presence.

The Signature is well fulfilling its mandate by resurrecting this rarely seen work, which lasted a mere twelve performances upon its 1980 Broadway premiere. But while it received a critical drubbing at a time when the playwright was in a definite career slump, this revival strongly makes the case that--while not one of Albee’s major works—it definitely deserves reconsideration.

It begins in a fashion recalling his classic Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, with three couples engaged in a party game in a well-appointed suburban home which, like the domestic battleground in God of Carnage, is decorated with African tribal art.

The game is 20 Questions, which is never conducive to peace and harmony but does lead one of the characters to ask the existential question, “Who am I?” The participants include hosts Sam (Michael Hayden) and his wife Jo (Laila Robins); next-door neighbors Edgar (Thomas Jay Ryan) and Lucinda (Catherine Curtin); and Sam’s best friend, Fred (C.J. Wilson) and his latest, younger girlfriend Carol (Tricia Paoluccio).

It soon becomes apparent that Jo is ill--terminally ill in fact--and is subject to bouts of horrific pain. The gathering thus ends early, but not before the arrival, just before the first act curtain, of a beautifully dressed older woman (Alexander) and her dapper African-American companion (Peter Francis James).

When a bleary-eyed Sam stumbles upon them the following morning, he’s more than a little discomfited, especially since the “Lady from Dubuque” claims to be Jo’s mother. Meanwhile, her cohort, Oscar, proves to be a rather menacing figure, mocking the confused Sam and adopting an exaggerated shuffle and dialect when his race is pointed out.

The rather contrived return of the previous evening’s guests creates further conflict, with Sam eventually being rendered unconscious by Oscar via a Vulcan-like nerve pinching. But when a clearly agonized Jo eventually makes her way downstairs, she immediately takes comfort in the presence of her female visitor, who embraces her like the mother she pretends to be.

Although the play is not exactly subtle in its allegorical conceit of death, it nonetheless exerts an undeniable fascination thanks to Albee’s gift for blending nasty humor, poignant drama and cosmic ideas in compelling fashion.

This revival staged by David Esbjornson expertly mines the work’s elemental power, and is beautifully acted by the ensemble. Although anyone who saw the original production could never forget the thrilling performances by Irene Worth and Earle Hyman as the mysterious visitors, Alexander and Frances James are superb successors, with the latter entertainingly mining his character’s droll humor.

After this successful resuscitation, more exploration of the Albee canon is clearly warranted. One can hardly wait to see what this adventurous company might do with the notorious 1983 flop, The Man Who Had Three Arms.

Pershing Square Signature Center, 480 W. 42nd St. 212-244-7529. www.signaturetheatre.org. Through April 15.