Category: "Off-Broadway"

Review: Farm Boy

Dec 22nd

In what surely must be purely coincidental timing, Farm Boy has arrived for a holiday engagement at 59E59 Theaters. Michael Morpungo’s “sequel” to his War Horse has opened just as Steven Spielberg’s big-budget film adaptation hits theaters, and while the Lincoln Center production is still attracting record crowds. Unfortunately, this slight, two-character chamber piece registers less as a sequel than a footnote. Audiences expecting to see more of the equine hero Joey will be sorely disappointed.

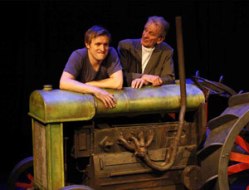

Admittedly, this 65-minute one-act adapted and directed by Daniel Buckroyd which successfully toured the U.K. has its charms. Performed on a stage dominated by a rusty old life-sized tractor, it concerns an elderly farmer (John Walters) and his young grandson (Richard Pryal).

The grandfather, it turns out, is the son of Albert, the young man who figured so prominently in War Horse. After a perfunctory rehashing of the events of that earlier work, this play’s main plot element involves a plowing contest between Albert and Joey and a tractor, with the latter as the prize. That we’ve spent nearly an hour staring at the object in question leaves little doubt as to the outcome.

Otherwise, the homespun dialogue touches on such issues as the death years earlier of the grandfather’s wife and his never having learned to read or write. Underscoring the proceedings is a suitably gentle piano score composed by Matt Marks.

It’s all very innocuous, although it’s hard to tell who the show is geared for since it seems too elevated for children and too mild for adults. There’s no denying the heartfelt sincerity of the piece or the effectiveness of the performances, especially Walter’s physically fragile but talkative grandpa. But it’s hard not to miss Joey, who, let’s face it, is the heart and soul of War Horse.

59E59 Theaters, 59 E.59th St.212-279-4200. www.59e509.org.

Review: Misterman

Dec 20th

The cavernous St. Ann’s Warehouse provides the perfect theatrical environment for Misterman, Irish playwright Enda Walsh’s one-person play starring Cillian Murphy in his U.S. stage debut. The actor--best known on our shores for his intense turns in such hit films as The Dark Knight and Inception—delivers a nearly aerobic performance as he ricochets around the environs of the massive space which simultaneously evokes an abandoned factory and the messy recesses of his character’s disintegrating psyche.

First staged in 1999, this work by the author of such plays as Disco Pigs, Penelope and The Walworth Farce (all of which also received their American premieres at this venue) features Murphy as Thomas Magill, a religious fanatic who has made it his mission to bring divine salvation to the denizens of the town of Inishfree.

He has documented his efforts on a series of audio recordings, snippets of which are heard being emitted by the numerous tape recorders scattered around the junk-laden space. As Thomas delivers a stream-of-consciousness monologue that becomes increasingly disjointed and surreal, he provides the voices of several of the townspeople, who are not exactly receptive to his desperate exhortations. He also engages in a running dialogue with his “Mammy,” demonstrating that the crazy apple doesn’t fall far from the tree.

The stylized proceedings become increasingly tiresome over the play’s 80-minute running time, and viewers may at times be hard-pressed to figure out exactly what’s going on. But there’s no denying the virtuosity of Murphy’s fiercely visceral performance, the highlight of which is his solo depiction of a beating inflicted on Thomas that is a masterful display of physical acting.

Adding greatly to the overall impact are the stunning production elements, including Jamie Vartan’s awesomely detailed set that seems to reveal new facets with every glance, and the bravura sound design by Gregory Clarke that conjures everything from barking dogs to the bucolic sounds of a pastoral village.

But the main special effect is Murphy himself. When he directs his gaze—featuring those much-commented upon, piercing blue eyes—at the audience, the results are hypnotic. His character may indeed be crazy, but we would probably follow him anywhere.

St. Ann’s Warehouse, 38 Water St. Brooklyn, NYC. 718-254-8779. www.stannswarehouse.org.

Review: Elective Affinities

Dec 16th

Good luck scoring an invitation to the most exclusive social reception in town. It’s being held at the palatial and luxurious Fifth Avenue townhouse belonging to the very wealthy Mrs. Alice Hauptmann. There you will be treated to tea, finger sandwiches, and a healthy dose of the vitriol at the heart of this fiendishly funny dowager.

The event is not real, of course, but actually a very clever, site-specific theater piece (presented by Soho Rep, piece by piece productions and Rising Phoenix Repertory) and starring the legendary Zoe Caldwell. Written by David Adjmi (Stunning) and directed by Sarah Benson, Elective Affinities is an intriguing if ultimately slight piece--very slight, actually, since the play itself runs a mere 30 minutes or so. But this intimate experience, done for just thirty audience members an evening, offers the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to experience a near-private performance by this great actress.

Upon entering the premises--the private location of which is sent to you a couple of days in advance via e-mail--one is greeted by an officious staff who check your coat and guide you to the upstairs drawing room. While a pianist plays classical music you can gaze at the enormous and horribly ugly abstract black sculpture that sits in the middle of the room.

Eventually you are personally welcomed by Mrs. Hauptmann herself, who just might greet you as if you’re an old friend and make such inquiries as whether or not your daughter has gotten into that university to which she was applying. You settle into another room, sitting on couches, chairs, divans, wherever you can, as your host proceeds to regale you with a rambling philosophical monologue in which she discusses subjects ranging from the Darwinian aspects of nature to the necessity of torturing terrorist suspects.

Chatty and convivial, she quickly reveals her true colors. “I love my husband, my friends,” she declares. “Other people, I’m indifferent to them. Until they harm me…or someone I love. Then I’m not indifferent. Then you can permit horrible things—torture, murder, genocide, that sort of thing.”

Clearly influenced by Wallace Shawn’s similarly monstrous character in Aunt Dan and Lemon, Mrs. Hauptman pales by comparison, and so does this brief playlet. But it’s nonetheless a haunting experience, not diminished at all by the fact that Caldwell performs with the script in front of her. Simply being in the intimate company of this theatrical giant is a privilege well worth paying for.

“Hauptmann Residence,” New York City. 212-352-3101.

Review: Once

Dec 7th

When the indie film musical Once was released five years ago, it became a critical and box-office sensation. This touching tale of the relationship between a Dublin Irish street musician and the Czech émigré who helps him find his musical voice had a refreshingly modest charm. So it was heartening to hear that its theatrical adaptation would be receiving its world premiere at the New York Theatre Workshop, clearly not a venue for glitzy, overblown musicals.

And yet, for all the modesty of its approach, this version still seems somewhat glossy and bloated. For one thing, the simple tale, told in just 90 minutes on film, now runs nearly two-and-a-half hours. And the lead characters, dubbed just “Guy” and “Girl,” are no longer the scruffy, realistic figures originally embodied so memorably by Glen Hansard and Marketa Irglova, who also wrote the music and lyrics. Here, they are played by Steve Kazee, so Adonis-hunky that it’s a wonder that his character hasn’t already reached stardom of Bruce Springsteen proportions, and Cristin Milioti, so cutely adorable that she should be the star of her own sitcom.

Since the stage production couldn’t exactly replicate the streets of Dublin, Bob Crowley’s evocative set recreates the most Irish thing imaginable—a pub. Indeed, before the show starts, the cast members are up on stage having a rowdy time singing and playing musical instruments, with audience members welcome to come up and buy drinks at the “bar,” free to either linger for a while onstage or bring them back to their seats.

The ensemble--many of them doubling as musicians--sits around the perimeter of the set when not involved in the action. Among the standouts are David Patrick Kelly, as the Guy’s elderly Da; Paul Whitty, as a protective friend of the Girl; and Andy Taylor, as a bank manager comically self-deluded about his own musical talents.

The score, all of which comes from the film, retains its folksy appeal, even if it’s not particularly theatrical--the standout, not surprisingly, is the gorgeous, Oscar-winning “Falling Slowly.” It’s all beautifully sung by the cast who—thanks to the movement choreographed by Steven Hoggett (Black Watch)—also imbue their musicianship with tremendous physicality.

The book by Irish playwright Enda Walsh (Penelope, The Walworth Farce) is rather too elongated, but it’s also undeniably witty and certainly sharper than the film version, which had a semi-improvised feel. And John Tiffany has staged the proceedings with a smooth fluidity that keeps the action flowing nicely.

I wish I could say that I fell in love with Once the way that I suspect many audiences are bound to. But then again, that’s the way love is, isn’t it?

New York Theatre Workshop, 79 E. 4th St. 212-279-4200. www.ticketcentral.com.

Review: The Cherry Orchard

Dec 6th

The stifling languorousness that so often afflicts contemporary productions of Chekhov is thankfully nowhere in sight in this Classic Stage Company’s revival of The Cherry Orchard. Directed by Andrei Belgrader and featuring a stellar cast including Dianne Wiest, John Turturro, Daniel Davis, Juliet Rylance, Roberta Maxwell, Josh Hamilton, Michael Urie and the great Alvin Epstein, this literally lighter version is very easy to take.

For starters, the new translation by John Christopher Jones (a veteran actor with no shortage of Chekhov experience himself) manages to trim the play to a fast-paced two-and-a-quarter hours including intermission without leaving it feeling overly truncated. The language is easy on modern ears, but not anachronistic.

The lightness of tone is immediately established by Santo Loquasto’s all-white set, featuring a tiny miniature of a train, which is revealed by the parting of a gauzy curtain.

Unevenness of tone and acting styles is almost always a problem with Chekhov productions, but this rendition is more graceful than most. Director Belgrader has elicited terrific performances from his ensemble, beginning with Wiest, who previously excelled in the same venue in a production of The Seagull. The actress brings a tremulous vulnerability to Ranavskaya, the financially bereft owner of a large estate that her scheming neighbor Lopakhin (Turturro, providing his usual compelling intensity) proposes be divided into small lots.

Daniel Davis is equally moving as Gaev, her equally self-deluded, pie-in-the-sky, older brother, while Juliet Rylance is luminous as Varya, the daughter with whom Lopakhin is hopelessly in love.

The smaller roles are expertly handled as well. Josh Hamilton is touching self-effacing as the young radical Trofimov; Siblings Katherine and Elizabeth Waterston are both beautiful and engaging as the miserable daughter Anya and randy servant Dunyasha respectively; Michael Urie is amusing as the fumbling servant Trofimov; and Roberta Maxwell is hilarious as the governess Charlotta, even if her interactions with various audience members are a little over-the-top.

And of course there’s Epstein, as the forlorn, aged servant Fiers, who is so poignantly abandoned at the play’s conclusion. Shuffling onto the stage wearing his nightshirt, he single-handedly embodies the playwright’s weaving together of pathos and humor that this production so effectively realizes.

Classic Stage Company, 136 E. 13th St. 212-352-3101. www.classicstage.org.