Category: "Review"

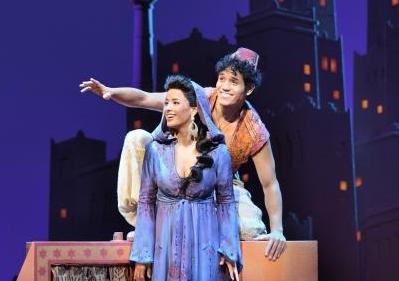

Review: Aladdin

Mar 21st

Courtney Reed and Adam Jacobs in Aladdin

(©Deen van Meer)

When James Monroe Iglehart sings “Friend Like Me” in Disney’s new Broadway musical adaptation of its classic animated hit Aladdin, truer words were never sung. Playing the role of the Genie, voiced so memorably by Robin Williams in the film, the performer is indeed this show’s best friend and most potent weapon. Coming at nearly the halfway point, his show-stopping number lifts the previously moribund evening to dizzying heights.

The latest in Disney’s many attempts to translate its cinematic magic to the stage, Aladdin falls well short of the heights of Beauty and the Beast and The Lion King or even Mary Poppins while being superior to such misbegotten efforts as Tarzan and The Little Mermaid.

Featuring songs from the movie composed by Alan Menken with lyrics by Tim Rice and the late Howard Ashman as well as new numbers featuring lyrics by Chad Beguelin, who also wrote the book, the show is largely faithful to the source material. It tells the tale of the rakish Aladdin’s (Adam Jacobs) courtship of the Sultan’s (Clifton Davis) beautiful daughter Jasmine (Courtney Reed). Aiding him in his romantic pursuit is the Genie, who has granted him three wishes, even as the Sultan’s evil advisor Jafar (Jonathan Freeman, who voiced the role in the movie) threatens to prevent the young lovers from getting together.

Coming across as a sort of Middle East version of A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum—there’s even an introductory number, “Arabian Nights,” that strongly recalls “Comedy Tonight”—the musical traffics in the sort of slapstick, shtick-laden humor that more often produces groans than laughs. Most of the tired jokes involve Aladdin’s three buddies (Brian Gonzales, Jonathan Schwartz, Brandon O’Neill) whose antics recall the Three Stooges at their least inspired.

It’s when the Genie finally gets released from his bottle that the show truly comes to life. The burly Iglehart wisely makes no attempt to duplicate Robin Williams’ iconic performance, instead delivering a distinctive, boisterously funny, physical turn that is consistently hilarious. Despite his ample girth, the performer fairly bounds across the stage, even doing a somersault at one point, and his spearheading of the “Friend Like Me” number, terrifically choreographed by director Casey Nicholaw, garnered a mid-show standing ovation at the reviewed performance.

The rest of the score, especially the new numbers, is largely unmemorable, with the other highlight predictably being the gorgeous ballad “A Whole New World,” beautifully staged with Aladdin and Jasmine atop a flying magic carpet courtesy of master illusion designer Jim Steinmeyer, whose previous credits include Beauty and the Beast, Phantom of the Opera and Mary Poppins.

While the attractive Jacobs and Reed are appealing if generic in the lead roles, the rest of the large ensemble mostly struggle to get the sort of laughs that Iglehart seems to achieve so easily.

The scenic designs by Bob Crowley, while displaying a fast-moving versatility, look rather cheap, especially in comparison to the endless array of dazzlingly colorful costumes designed by Gregg Barnes.

Despite its largely pedestrian execution, Aladdin has a decent chance of achieving hit status, if only for the familiarity of its title. But even with its miraculous flying carpet, the show remains stubbornly earthbound.

New Amsterdam Theatre 214 W. 42nd St. 866-870-2717. www.AladdinTheMusical.com.

Review: Rocky

Mar 14th

Andy Karl in Rocky

(©Matthew Murphy)

You’ll leave the new Broadway musical Rocky humming the score. Unfortunately, it won’t be the wholly unmemorable one by veteran composers Stephen Flaherty and Lynn Ahrens (Ragtime, Once on This Island) but rather such music featured in the original 1976 film and its sequels as Bill Conti’s stirring theme and the rock hit “Eye of the Tiger” by Survivor, both of which are generously spotlighted.

Oh, did I mention you’ll also be humming the scenery? Christopher Barreco’s elaborate, endlessly shifting sets for this hugely expensive production are indeed awe-inspiring.

The latest in a seemingly never ending series of musicalizations of beloved films, Rocky seemed like a dubious bet for such treatment. Although its storyline about a struggling small-time boxer who finds self-redemption via a one-in-a-million title bout with a reigning champ--as well as love with the mousy girl he inspires to come out her shell--has a powerful elemental quality, its gritty aspects don’t exactly inspire visions of song and dance.

This musical version of the film that made Sylvester Stallone a superstar doesn’t exactly dispel that notion. But thanks to its iconic characters and a brilliant staging courtesy of director Alex Timbers, it emerges as a genuine crowd-pleaser that, much like its titular hero, manages to go the distance.

Co-written by the incongruous team of Stallone and Thomas Meehan (Annie, The Producers), the musical is slavishly faithful to its inspiration, telling the Philadelphia-set story of Rocky Balboa (Andy Karl), the “Italian Stallion” who’s reduced to low-end bouts and making a living as an enforcer for a loan shark. He’s desperately in love with Adrian (Margo Siebert), the sister of his best friend Paulie (Danny Mastragiorgio), but although she returns his affections she’s far too repressed to act on them.

Rocky’s life changes when he’s suddenly plucked out of obscurity to fight the champion, Apollo Creed (Terrence Archie), after his original title bout opponent is injured. Creed, who picked Rocky because of his colorful nickname and appealing hard luck story, expects to make short work of the untested fighter. But as everyone in the audience undoubtedly already knows, that’s not to be the case.

The sluggish first act recreates many of the film’s iconic scenes with a slavish fidelity that inspires boredom. Rest assured that you’ll hear Rocky bellow “Yo Adrian” more than a few times and that you’ll be reintroduced to such familiar characters as his snappish trainer Mickey (Dakin Matthews). Flaherty and Ahrens’ ballad-heavy score is similarly uninspired, with the exception of one or two catchy songs like Rocky’s solo number “My Nose Ain’t Broken.”

But director Timbers really kicks things up a notch in the second half with a couple of exuberant training montages and particularly with the climactic boxing match featuring terrific pugilistic-inspired choreography by Steven Hoggett and Kelly Devine. To reveal the details of the incredibly inventive staging would be to spoil the surprise. Suffice it to say that it involves a movable regulation-size boxing ring, a giant multi-screen Jumbotron, and an all-around immersive quality that truly involves the audience in the action. To say that all the hoopla was greeted by rapturous cheers would be an understatement.

Karl, although a bit too slight to make for a convincing heavyweight, brings real charm to the role, channeling just enough of Stallone to satisfy the film’s fans while also making it his own. The supporting players, by contrast, pale in comparison to their cinematic predecessors. Seibert’s Adrian lacks Talia Shire’s sublime poignancy, and Mathews, Archie and Mastrogiorgio fail to supply the comic grace notes that Burgess Meredith, Carl Weathers and Burt Young infused into their performances.

On the way out, a fellow critic commented, “What are we even doing here?” It was an apt question. For all its flaws as a musical, the show feels genuinely critic-proof. It seems very likely that Rocky will be fighting at the Winter Garden for a long time to come.

Winter Garden, 1634 Broadway. 212-239-6200. www.telecharge.com.

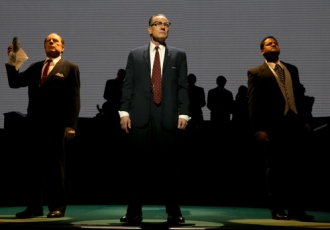

Review: All the Way

Mar 7th

Michael McKean, Bryan Cranston, and Brandon J. Dirden in All the Way

(©Evgenia Eliseeva)

Playing Lyndon B. Johnson in Robert Schenkkan’s ambitious historical drama All the Way, Bryan Cranston commands the stage in the same manner that LBJ commanded politics. Making his Broadway debut, the Emmy-winning star of Breaking Bad delivers a powerful, canny performance that constantly mesmerizes, even if the nearly three-hour drama he inhabits at times suffers from a wearisome overload of incidents and information.

Set in 1963-1964 from Johnson’s ascent to the Presidency after the JFK assassination to his triumphant election the following November, the play largely concentrates on his determined efforts to pass the Civil Rights Act despite the fervent opposition of Southern congressmen and his battle to win the presidency in his own right. It vividly depicts the nuts-and-bolts of LBJ’s strong-arm manipulations in great detail, with its large cast of characters including such figures as his wife Lady Bird (Betsy Aidem); Hubert Humphrey (Robert Petkoff), who would later become his Vice-President; the veteran Southern senator Richard Russell (John McMartin), one of his closest colleagues; his arch-rival, Governor George Wallace (Rob Campbell); FBI director J. Edgar Hoover (Michael McKean) and such civil rights leaders as Martin Luther King, Jr. (Brandon J. Dirden), Ralph Abernathy (J. Bernard Calloway) and Stokely Carmichael (William Jackson), among many others.

The playwright, who won the Pulitzer Prize for his The Kentucky Cycle, is no stranger to large-scale historical drama, and he conveys the complicated tale with assured skill. The characterizations and sharply written dialogue ring true, and the complex political maneuverings are rendered with an uncommon clarity, abetted by Shawn Sagady’s projections featuring archival film footage and helpful identifications of many of the supporting characters.

But despite its admirable ambitions the play never quite manages to be sufficiently compelling, lacking the theatrical power to elevate it above the level of an informative history lesson. That it works to the extent that it does is largely due to Cranston’s compelling performance. The actor, looking uncannily like Johnson with the aid of unobtrusive prosthetics and affecting a convincing Texan accent, superbly depicts the master politician’s wily intelligence and blustering personality as well as the tragic personality flaws that would ultimately undermine his presidency.

Under Bill Rauch’s cohesive direction, the large ensemble, many of them playing multiple roles, delivers mostly fine support, with the exceptions being Dirden, who fails to convey King’s charismatic magnetism, and McKean, miscast as the menacing Hoover.

It’s not surprising that this large-scaled play with its massive cast would be presented in the Neil Simon Theatre, normally a musical house. But commercial considerations aside, it would be far more effective in a more intimate venue. Christopher Acebo’s stark set, composed largely of semi-circular wooden benches, fails to impress, and such theatrical touches as having confetti rain down on the audience in celebration of Johnson’s electoral victory seem pro forma.

But for all its flaws, All the Way is to be commended for its intelligence and ambition. Such serious dramas, especially those with large casts, are a rarity on Broadway these days. Credit must no doubt go to Cranston’s star power, and the talented actor doesn’t disappoint. His bravura performance, sure to be recognized come awards time, registers as a highlight of the theater season thus far.

Neil Simon Theatre, 250 W. 52nd St. 800-745-3000. www.Ticketmaster.com. Through June 24.

Review: Kung Fu

Feb 25th

Frances Jue and Cole Horibe in Kung Fu

(©Joan Marcus)

The title of David Henry Hwang’s bio-play about Bruce Lee is ironic in a way that the screen icon would surely have appreciated. It refers not only to the martial arts style for which he was renowned, but also the classic television series he developed as a starring vehicle for himself, only to see a white actor, David Carradine, given the lead role.

Sadly, its title is the most resonant aspect of this stylized effort from the playwright whose previous works include the award-winning M. Butterfly, Golden Child, The Dance and the Railroad and the recent Chinglish. Starring So You Think You Can Dance contestant Cole Horibe in the starring role, this Signature Theatre Company production presents a sketchy, dramatically thin portrait of Lee’s life from his early days in Hong Kong to his eventual return to his birthplace and ascent into screen superstardom after a frustrating sojourn in Hollywood.

The play’s principal theme is Lee’s strained relationship with his domineering father (Frances Jue), whose constant disapproval supposedly led to his intense drive and perfectionism. While it may indeed be true, it’s handled with a Psychology 101 heavy-handedness that fails to sustain interest.

Hwang dutifully touches the biographical bases, including Lee’s relationship with his American wife Linda (Phoebe Strole) and young son Brandon (Bradley Fong); his difficulties getting cast in Hollywood because of his thick accent and the industry’s inherent racism; his martial arts tutoring of such stars as Steve McQueen and James Coburn (Clifton Duncan); and his frustration with his subservient role as Kato in the short-lived television series The Green Hornet. The play ends when he bitterly returns to Hong Kong, a decision that would prove highly fortuitous to his career.

Lee was a fascinatingly complex and charismatic figure, but little of that is apparent here due to the thinness of the writing and the uncharismatic performance by Horibe in his first dramatic role. While the performer certainly possesses the necessary lithe physique and athletic grace, he conveys little of the star’s fierce intensity that galvanized worldwide audiences.

The most striking moments of Leigh Silverman’s fast-paced production are the extensive, beautifully choreographed fight sequences staged by Emmanuel Brown. They manage to be both highly convincing and visually exciting while managing the neat trick of not doing physical harm to the actors. Less felicitous are the numerous dance sequences choreographed by Sonya Tayeh, including an interpretive dance performed to the propulsive Green Hornet theme music and a climactic Chinese-style ballet accompanied by an electronic score. They seem mere filler, tacked on to extend the play’s brief, two hour running time. The non-traditional casting choices are also jarring, including having an African-American actor as Coburn and an Asian-American as TV producer William Dozier.

But the chief problem is the play itself. The flashback sequences depicting Lee’s contentious relationship with his father prove repetitive, and such scenes as when Lee lies immobile on the floor after an injury go on far too long while having little dramatic impact.

Ultimately it all comes across as a misfire, a particularly disappointing one considering the richness of the subject matter and Hwang’s proven ability to explore his themes with greater depth. Kung Fu gives the superficial appearance of making all the right moves, but it fails to land any true body blows.

Pershing Square Signature Center, 480 W. 42nd St. 212-244-7529. www.signaturetheatre.org. Through March 16.

Review: The Bridges of Madison County

Feb 21st

Kelli O'Hara and Steven Pasquale in The Bridges of MadisonCounty

(©Joan Marcus)

Is it too much to ask of a show called The Bridges of Madison County that we actually see one of the covered bridges that provide its title?

Sure, Michael Yeargan’s set design dutifully represents one of the archetypal structures with a series of arches. But much like this simultaneously intimate and overblown musical adapted from Robert James Waller’s gazillion-selling 1992 novel, it feels woefully inadequate.

Millions of people, probably most of them middle-aged women, swooned to the literary source material which was also made into a 1995 film directed by and starring Clint Eastwood, with Meryl Streep in the role of Francesca, the Italian war bride who has long settled into a boring marriage with an Iowa farmer.

This musical version featuring a score by Jason Robert Brown (The Last Five Years, Parade) and book by Marsha Norman (‘night Mother, The Color Purple) is no doubt aiming for a similar demographic. But from the plaintive sound of a cello in its opening moments to its ghostly reunion between the ill-fated lovers at the end, it strikes nary an unpredictable note.

The show directed by Bartlett Sher, first seen at the Williamstown Theatre Festival, concerns the fateful meeting between Francesca (Kelli O’Hara), married for eighteen years to the inattentive Bud (Hunter Foster), and Robert Kinkaid (Stephen Pasquale), a ruggedly handsome National Geographic photographer who has arrived in the flatlands of Iowa to photograph its celebrated covered bridges. One day Robert literally shows up on her doorstep, with Francesca, whose husband and two children have left for several days to attend a state fair, eagerly welcoming him in.

It doesn’t take long for Francesca and Robert, fueled by a bottle of brandy and some tender slow-dancing to the radio, to embark on a torrid affair that reawakens passionate nature that has been smothered by years of household drudgery. Lying to her husband Bud (Hunter Foster) and evading the suspicions of her busybody and rather jealous neighbor Marge (Cass Morgan), Francesca begins to seriously contemplate Robert’s offer to run away with him and share his wanderlust.

The schematic storyline was given great resonance in Eastwood’s subtle film adaptation. But there’s little subtlety in this show which hammers home its romantic themes in oppressive fashion. Brown’s score which aspires to operatic heights with its assemblage of soaring aria-like ballads is lush and melodic. But it eventually wears you down with its overly heightened emotionalism that is only partially alleviated by a country-flavored numbers.

Norman strains the simple storyline with a surfeit of extraneous characters and situations, including subplots involving the relationship between Marge and her common-sense spouting husband Charlie (Michael X. Martin) and endless segues to Francesca’s family at the state fair and the sibling rivalry between her daughter Carolyn (Caitlin Kinnunen) and son Michael (Derek Klena). Most egregiously, the main action is followed by a lengthy melodramatic coda filling us in on the two principal characters’ lives after their four day encounter. What might have made for an affecting 90-minute chamber musical is here stretched out to a numbingly bloated two hours and forty minutes.

Sher’s staging is also overly fussy, with scenery constantly being wheeled back and forth and the minor characters observing the action as if they were audience members who were mistakenly assigned onstage seats.

O’Hara (affecting a reasonably convincing Italian accent) and Pasquale make for an attractive couple, and their chemistry—they also co-starred in the off-Broadway musical Far From Heaven—is palpable. Both deliver strong, affecting performances that are enhanced by their superb vocalizing of the demanding score, including a second act ballad, “One Second and a Million Miles,” which justifiably stops the show. Strong contributions are also made by Foster, who provides unexpected shadings to his potentially stereotypical role, and Morgan, very amusing as the overly curious neighbor.

But for all its blatant attempts to tug at the heartstrings, The Bridges of Madison Country remains curiously unmoving. It’s as if its creators assumed that the source material was so potent in its melodramatic themes that all they had to do was accentuate them. But sometimes less is more.

Gerald Schoenfeld Theatre, 236 W. 45th St. 212-239-6200. www.Telecharge.com.