Category: "Off-Broadway"

Review: By the Way, Meet Vera Stark

May 23rd

Lynn Nottage’s new comedy couldn’t be more different from her last effort, the Pulitzer Prize winning, Rwanda-set Ruined. A satirical portrait of the subservient roles assigned to black performers in 1930s Hollywood--and decades afterwards, for that matter--By the Way, Meet Vera Stark features enough intelligence, wit and insight for two plays, which in fact this one essentially is. While its disparate halves never quite coalesce into a fully satisfying work, there’s still plenty to appreciate.

Sanaa Lathan delivers a standout performance in the title role of an African-American maid to a white movie star (Stephanie J. Block), who is up for the lead role as an octoroon Southern belle in a Gone With the Wind-style Hollywood epic. Vera is anxious to break into the movies as an actress herself, as is her caustic roommate Lottie (Kimberly Herbert Gregory), but the only roles open to them are, well, maids.

The evening’s first half is a screwball comedy ala George S. Kaufman, as Vera deals with her needy employer’s neuroses while working at a dinner party whose guests include a Jewish studio executive (David Garrison) and a pretentious director (Kevin Isola). Also showing up are Vera’s actress friend (Karen Olivo) who’s attempting to pass herself off as a Latina in order to land roles, and a smooth talking chauffeur (Daniel Breaker) with whom Vera’s enjoying a flirtation.

Act II takes a wildly divergent tone. Set four decades later, it revolves around a film symposium dedicated to Vera’s subsequent life and career, hosted by an unctuous intellectual (Breaker). As he and his fellow panelists, including a college professor (Gregory) and an radical poet (Olivo), pontificate about their subject, we see “clips” from a 1973 talk show appearance in which Vera, who went on to become a cheesy Las Vegas headliner, is reunited with her former employer and, as we learn, eventual cinematic co-star.

The evening is fairly bursting with wit, with a particular highlight being the expertly executed mock excerpt from “The Belle of New Orleans,” the film that made Vera a star. And Nottage’s skewering of academic pretensions is so hilariously spot-on that it almost feels like the real thing.

But the play’s satirical ideas, however thoughtful, are ultimately too scattershot and diffuse to sustain this full-length work. The warmth and insightful characterizations on display in the first half devolve into a less satisfying, sketch-like quality in the second.

The production itself is impeccable, from the ingenious staging by Jo Bonney that uses such clever devices as cinematic dissolves for transitions between scenes, to the sets and costumes that hilariously evoke the various periods in which the play is set.

And the acting is superb, from Lathan’s emotionally complex Vera to Block’s hilarious diva to the rest of the ensemble’s wildly divergent dual turns.

Second Stage Theatre, 305 W. 43rd St. 212-246-4422. www.2ST.com.

Review: A Minister's Wife

May 20th

A little show called My Fair Lady provides ample demonstration that the works of George Bernard Shaw are certainly ripe for musical treatment. But the latest attempt, A Minister’s Wife, illustrates the pitfalls as well. This chamber musical adaptation of his 1898 play Candida ironically only serves to detract from the music of his language.

Austin Pendleton has hewed quite faithfully to the original with this condensed adaptation, although he has taken such liberties as removing the character of Candida’s lowbrow father.

But something has definitely been lost in translation. This version lacks the rich humor of Shaw’s play about a minister’s wife (Kate Fry) forced to choose between the affections of the Reverend James Morell (Marc Kudisch), her loving but endlessly distracted husband, and Eugene Marchbanks (Bobby Steggert), the impulsive young poet who has fallen desperately in love with her.

Would that the show sounded as lovely as it looks on Allen Moyer’s gorgeous, beautifully detailed set. But the score, written by Joshua Schmidt (music) and Jan Levy Tranen (lyrics) and performed by a four-piece ensemble, is one of those wan, minimalist affairs that barely makes an impression. It consists less of musical numbers than endlessly talky recitatives that, combined with the soft lighting, ultimately have the effect of lulling the audience into a gentle repose.

Still, the wit and intellectual vigor of Shaw’s play inevitably comes through, and the evening is not without its minor pleasures. They stem mainly from the performances: Fry is both charming and formidable as the sensible Candida who nonetheless finds herself attracted to her inappropriate young suitor; Kudisch movingly conveys both Morell’s moral strength and emotional vulnerability; and Steggert, who sings beautifully here, well captures the delicate balance between Marchbank’s brashness and sensitivity.

The lack of specificity in the title is indicative of the wishy-washy nature of this unnecessary adaptation. A Minister’s Wife may technically qualify as a musical, but it doesn’t exactly sing.

Mitzi E. Newhouse Theater, 150 W. 65th St. 212-239-6200. www.lct.org.

Review: King Lear

May 10th

Most actors play King Lear as an imperial monarch, the better to contrast with the character’s subsequent descent into madness. But in the new production of the play at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, veteran British actor Derek Jacobi (of I, Claudius fame) takes a different approach.

Most actors play King Lear as an imperial monarch, the better to contrast with the character’s subsequent descent into madness. But in the new production of the play at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, veteran British actor Derek Jacobi (of I, Claudius fame) takes a different approach.

His Lear is a loving father in desperate need of his children’s tribute. When it’s denied him by his youngest, favorite daughter Cordelia (Pippa Bennett-Warner), he acts like a spoiled, petulant child. It makes his ensuing despair and humiliation more human and all the more heartbreaking.

His revelatory performance makes it easy to see why BAM imported this Donmar Warehouse revival when productions of this theatrical warhorse are positively ubiquitous. Indeed, there are two more arriving later this year; one courtesy of the Royal Shakespeare Company and another at the Public Theater starring Sam Waterston.

As has become standard in modern Shakespearean productions, this staging is a decidedly minimalist affair, performed on a bare stage composed of whitewashed wooden planks.

But that doesn’t stop director Michael Grandage from providing thrilling theatrical touches, most notably in the powerful storm scene in which lighting and sound effects are employed to harrowing effect.

But even then, it’s Jacobi’s unconventional acting choices that make the most impact. Rather than shouting his lines—most famously “Blow, winds, and crack your cheeks”--with the customary full volume, he whispers them, making us strain to hear this fallen monarch while he’s at his most vulnerable.

The actor is ably supported by the terrific ensemble, with particularly strong turns by Gina McKee and Justine Mitchell, chillingly low-key as the treacherous Goneril and Regan; Alec Newman, impressively villainous as the aggrieved Edmund, and Paul Jesson, heartbreakingly moving as the wronged Gloucester. Best of all is Ron Cook’s trenchant Fool who acerbically comments on the surrounding chaos.

The production admirably downplays the melodramatic bombast that afflicts so many current interpretations while restoring the play to its tragic psychological dimensions. Jacobi’s Lear is less a fallen monarch than an elderly parent desperately struggling to cope with the physical and mental infirmities accompanying old age.

BAM Harvey Theater, 651 Fulton St., Brooklyn. 718-636-4100. www.bam.org.

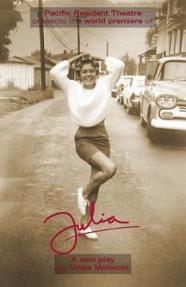

Review: Julia

May 9th

That life doesn’t always offer the opportunity to neatly right past wrongs is a promising theme for a drama. Too bad, then, that Julia squanders it.

The central character is Lou, a clearly ill man in his seventies who wanders into a rundown coffee shop. It’s soon revealed that he’s returned to his hometown to make amends to Julia, the girl he loved decades earlier and never saw again after he served in the Korean War. Her son refuses to have him upset his mother, now suffering from dementia in a nursing home. But when Lou literally gets on his knees and begs, he relents.

It’s here that the evening turns anti-climactic. A flashback to the fateful encounter between the younger Lou and Julia reveals immature anger but hardly the sort of behavior that would haunt someone for the rest of his life.

And when Lou is finally reunited with his former flame who doesn’t recognize him, the most dramatic moment centers around the pair eating snack cakes.

The acting, however, couldn’t be better. Richard Fancy, a familiar face from stage and screen (Being John Malkovich, Seinfeld), is deeply affecting as Lou, and Roses Prichard beautifully captures the confused daze of an Alzheimer’s sufferer.

59E. 59 Theaters, 59 E. 59th St. 212-279-4200. www.59e59.org

Review: The Intelligent Homosexual's Guide to Capitalism and Socialism with a Key to the Scriptures

May 6th

If the title of Tony Kushner’s new play premiere puts you off, wait until you actually sit through it. The overlong and overstuffed The Intelligent Homosexual’s Guide to Capitalism and Socialism With a Key to the Scriptures is typically Kushnerian in its seriousness, intelligence and wide-ranging themes, but this naturalistic drama is not nearly as effective as such works by the playwright as Angels in America or Homebody/Kabul.

Strongly reminiscent of Arthur Miller, the three-act work is mainly set in the Carroll Gardens neighborhood of Brooklyn, in a brownstone owned by Gus Marcantonio (Michael Cristofer), an avowed Communist and former longshoreman who has settled into a financially comfortable retirement.

Patriarch Gus has gathered his sister (Brenda Wehle) and grown children together to announce his plans to commit suicide, which he has attempted once before. He’s convinced that he’s suffering from Alzheimer’s disease, and is planning on selling his home to ensure financial security for his family.

The widowed Gus’ children, including oldest son Phil (Stephen Spinella), younger son V, short for Victor (Steven Pasquale) and daughter Empty (Linda Emond), are naturally aghast to hear of their father’s plans. Meanwhile, each is coping with various personal issues.

Phil, who has been in a longtime relationship with his African-American partner Paul (K. Todd Freeman), has spent a small fortune on the services of a male hustler (Michael Esper) with whom he is desperately in love. Empty is about to have a child via a surrogate (Molly Price) with her female lover Maeve (Danielle Skraastad) while enjoying the occasional sexual dalliance with her loyal ex-husband Adam (Matt Servitto). And working class V, married to the Asian-American Sooze (Hettienne Park), can barely contain his anger over his father’s decision.

The densely packed work—the title of which is a riff on writings by George Bernard Shaw and Mary Baker Eddy--offers a surfeit of characters and situations, more than Kushner can comfortably handle. Although it reveals the playwright’s gift for blending sexual, political and social issues with his trademark intelligence and biting humor, too much of the evening is composed of overheated domestic arguments.

These quickly prove tedious, especially in the overlong (3 and 3/4 hours) play’s second act, in which director Michael Greif has the actors loudly shouting while stepping over each other’s lines in a manner akin to the films of Robert Altman.

While some scenes resonate with dramatic power, the attenuated proceedings are mainly indicative of the playwright’s oft-demonstrated propensity for self-indulgence.

Performing on a beautifully detailed, two-story set designed by Mark Wendland, the ensemble, several of whom are veterans of previous Kushner productions, provide vividly memorable characterizations. Particularly outstanding are Spinella, who brings humor as well as desperation to Phil; Emond, who makes Empty sympathetic despite her selfish behavior; and Cristofer, who brings compelling forcefulness to his turn as the fervently leftist Gus.

Kushner’s undeniable talent is well on display in this ambitious but frustratingly problematic work. But it’s hard not to wish that the playwright had more sharply honed it since its Guthrie Theater premiere two years ago.

Public Theater, 425 Lafayette St. 212-967-7555. www.publictheater.org.