Category: "Review"

Review: Galileo

Feb 24th

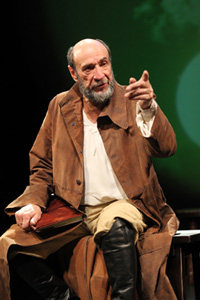

With partisan politics injecting itself into scientific debate with dismaying frequency these days, Bertolt Brecht’s Galileo has a disturbing modern resonance. While the Classic Stage Company’s revival of this rarely seen work doesn’t fully galvanize, it does offer the opportunity to watch Oscar winner F. Murray Abraham entertainingly sink his teeth into yet another juicy role.

Not that he over-emotes. In the title role of this play which bears any number of parallels with its playwright’s torturous political life, Abraham is all the more moving for his restraint. His matter-of-factness when depicting Galileo’s renunciation of his own theory about the earth orbiting the sun when he’s faced with torture is affectingly human.

Director Brian Kulick applies a number of typical Brechtian touches to his staging of the play, which is being presented in the translation by actor Charles Laughton that was first presented in 1947. But for all its ritualistic devices, songs and movement, the production is most affecting in its quieter, more subdued moments.

A first-rate supporting cast has been assembled, including Amanda Quaid as Virginia, the daughter whose burgeoning romance with a wealthy young man is threatened by her father’s controversial stands; Robert Dorfman as Cardinal Barberini, Galileo’s friend who is forced to betray him when he becomes pope; and Steven Skybell, Jon DeVries and Steven Rattazzi in multiple roles.

Adrianne Lobel’s set design, featuring floating orbs resembling planets, beautifully complements the play’s themes, with Justin Townsend’s lighting and Jan Hartley’s projections providing a suitably cosmic atmosphere.

Classic Stage Company, 136 E. 13th St. 212-352-3101. Through March 18.

Review: Early Plays

Feb 23rd

Although the stage seems bare for The Wooster Group’s production of Eugene O’Neill’s Early Plays, it actually contains an awful lot of baggage. The troupe is well known for their aggressively avant-garde approach to both new plays and the classics, adorning them with endless amounts of stylized movement and technological trickery. Meanwhile, guest director Richard Maxwell is typified by his minimalistic approach to both text and staging. The result of this unlikely collaboration is interesting if not wholly successful.

Of course, these early works by O’Neill—the production features three of his four one-act Glencairn plays set on or near a steamer and written in the first decade of the 20th century—would seem to defy modern staging. Deeply impressionistic and featuring dense and archaic dialect, they’re impenetrable at times. It’s no wonder that they’ve rarely been done even as the playwright has enjoyed a modern renaissance.

Maxwell’s approach here is to basically accentuate the text above all. And indeed it comes through with reasonable clarity, partly because a wise decision was made to have the actors avoid accents.

But the staging is pretty much non-existent. Performed on the same set that the company used for their production of The Emperor Jones, featuring just some cables and folding chairs (all the technical accoutrements, such as video screens, etc., are absent), the production has the feel of a staged reading…or more precisely, a table reading, and a first one at that. The actors vary wildly in their approaches, with some delivering fully formed, credible characterizations and other reciting their dialogue in a monotone that suggests they’ve never encountered it before.

That’s not to say that some effective atmospheric devices aren’t employed. The second play, Bound East for Cardiff, is performed in near total darkness, with only a spotlight at the rear of the stage to illuminate a couple of the actors. Musicians on the side of the stage provide a properly ominous background score. And the plays are bracketed by original, vintage-sounding songs composed by Maxwell that fit surprisingly well into the proceedings.

But despite some effective moments the production doesn’t manage to bring these works to any kind of vivid life. The task may perhaps be impossible, but it would be nice to see another attempt by a company with greater acting and directorial resources.

St. Ann’s Warehouse, 38 Water St. Brooklyn. 718-254-8779. Through March 11.

Review: Blood Knot

Feb 17th

It may be heretical to say, but seeing Athol Fugard’s landmark 1961 drama Blood Knot again, even in a superbly realized revival such as the one being presented by the Signature Theatre, is to be reminded how tedious it is. Such is the case, I’m afraid, with many of the playwright’s works, despite their historical and sociological importance. With one or two exceptions--Master Harold and the Boys being the most notable—Fugard’s dramas tend to be rambling and overly obvious in their themes. In most of them, you can be sure that the title will be dramatically uttered at one point, just to make sure we get the message.

This production--directed by the playwright and serving as the opener in a three-production season devoted to him—is the inaugural offering in the aptly named Alice Griffin Jewel Box Theatre in the company’s handsome new, Frank Gehry-designed theater complex dubbed The Pershing Square Signature Center.

The play concerns the relationship between two biracial South African brothers--one of whom is light enough to pass for white--who live together in a squalid shack on the outskirts of Port Elizabeth, South Africa. Zachariah (Colman Domingo) is a devil-may-care laborer at a whites-only park where his main job is to keep out his fellow blacks. The light-skinned, more ambitious Morris (Scott Shepherd), who has returned to his brother after a long absence, has dreams of saving up enough money to buy a farm for the two of them to run together.

Virtually nothing happens in the lengthy first act of this 2½ hour play, with the brothers engaging in lengthy verbal horseplay, much of it involving Morris’ efforts to procure a female pen pal and eventual love interest for his brother. Unfortunately, she turns out to be white.

Things turn slightly more dramatic in the second half, although the chief conflict revolves around a game of play-acting in which Morris gets all too carried away with his role as a white man and lets loose with a racial epithet that threatens to tear him and his brother apart. It foreshadows the later but similar angry prejudicial exchange that would figure so prominently, and to far greater effect, in Master Harold.

The venue’s intimacy certainly enhances the production’s impact, with the superb, fully lived-in performances by the two actors registering with a visceral intensity. Equally effective is Christopher H. Barreca’s rickety, ramshackle set, which is perched on a platform surrounded by detritus and literally comes apart in the play’s final moments, eerily mirroring the emotional desolation of the characters.

The Fugard season continues with a revival of his 1989 My Children! My Africa! followed by the New York premiere of The Train Driver.

Pershing Square Signature Center, 480 W. 42nd St. 212-244-7529. Through March 11.

Review: Look Back in Anger

Feb 3rd

It’s ironic that John Osborne’s classic drama Look Back in Anger is now as much of a period piece as the “well-made plays” it was attempting to usurp. This work--which revolutionized British theater when it received its 1956 premiere at the Royal Court and popularized the concept of the “angry young man”—can easily come across as a dated relic unless infused with sufficient energy and passion.

Thankfully, those qualities are well evident in the revival presented by the Roundabout Theatre Company. Forcefully and imaginatively staged by Sam Gold and featuring first-rate performances by its four-person ensemble—that’s not a typo, as one minor character has been excised—the production effectively suggests the power that the original must have had, even if it necessarily can’t duplicate it.

The iconoclastic nature of the staging is evident upon entering the theater. Just as its first audiences were supposedly startled by the mere sight on an ironing board on stage, Andrew Lieberman’s set design here is equally arresting. To be technical, there isn’t much of a set. The actors are confined to the lip of the stage, performing in front of stark backdrop with only a few feet of room. The space is littered with a few battered pieces of furniture and much detritus, presenting a stylized spin on the usual realistic depiction of the characters’ squalid living space.

Inhabiting that space, as any drama student will recall, are Jimmy Porter (Matthew Rhys), a well-educated but working class Brit; his long-suffering wife Alison (Sarah Goldberg); and, most of the time, their best friend Cliff (Adam Driver), who acts as mediator when tensions flare.

At this point Jimmy’s railings against a stuffy, conformist society might seem antique. That is, if Occupy Wall Street and the current class warfare afflicting modern politics hadn’t rendered them all too relevant. So, unfortunately, is the depiction of the near abusive, co-dependent relationship between Jimmy and the more refined Alison, which is rendered with emotional sensitivity by Rhys and Goldberg. And the seemingly immediate substitution of Alison’s best friend Helena (Charlotte Parry) in Jimmy’s life after Alison leaves has a nastily ironic aspect that surely influenced Harold Pinter.

The staging is infused with theatrical touches that keep us slightly off-guard, such as the house lights staying on at times and the actors hovering at the sides of the house in full view when they’re offstage.

Ultimately, however, it’s the performances that must carry the work, and the ensemble here doesn’t disappoint. Rhys, making his New York stage debut after five seasons on TV’s soapy Brothers and Sisters, mines Jimmy’s combination of dark humor and angry intensity to great effect, with his Welsh accent recalling Richard Burton, who played the role in the film version. Goldberg, also making her stage debut here, beautifully conveys her character’s complex feelings towards the man she loves. The physically imposing Adam Driver is boisterously entertaining as the good-hearted Cliff, while Charlotte Parry does as well as possible with the more problematical role of Helena.

Look Back in Anger will never again have the same impact that it must have had upon its premiere. But this production certainly provides a hint of what those lucky audiences at the Royal Court must have felt more than half a century ago.

Laura Pels Theatre, 111 W. 46th St. 212-719-1300. www.roundabouttheatre.org. Through April 8.

Review: Russian Transport

Jan 31st

Beware sexy Russian men bearing gifts. That seems to be the primary message of Russian Transport, the new play by Erika Sheffer being given its world premiere by the New Group. This uneasy blending of family and crime-themed drama is all too predictable in its depiction of a Russian immigrant family being torn apart by the arrival of a relative from their home country who turns out to have nefarious ends in mind. While the material might work reasonably well as a film—shot in real-life locations that would lend it a natural authenticity—its artifices shine all too clearly onstage.

The Sheepshead Bay family consists of Misha (Daniel Oreskes) and Diana (Janeane Garofalo) and their Americanized teenagers, seventeen-year-old Alex (Raviv Ullman) and fourteen-year-old Mira (Sarah Steele). Their car service business is clearly struggling financially, as evidenced Diana’s demanding that Alex immediately hand over his paychecks from part-time job at a cell phone store.

Their day-to-day routine--marked by much would-be comic, profanity-laced squabbling--is interrupted by the arrival of Boris (Morgan Spector), Diana’s younger brother. Handsome and charming, Boris quickly wins over the teenagers, but his influence on Alex soon reveals a sinister edge, as he enlists him in his human trafficking operation by having him pick up newly arrived, young Russian girls at the airport and delivering them to their unfortunate fates.

You can see where the plot is going from the very beginning, and the attempts by the playwright to give it texture with endless family arguments—the characters snipe at each other with a comic ferocity that feels wholly artificial—proves wearisome. And such moments as when Mira impulsively kisses her uncle romantically and Alex and his father have a confrontation involving a gun he’s smuggled into the house fail to produce the intended shocks.

The business of the proceedings is accentuated both by Scott Elliott’s high-pitched direction and Derek McLane’s awkward two-level set design which makes some of the action difficult to see.

The actors pour much conviction into their performances, to uneven effect. Spector displays such a strong physical presence and charisma that his galvanizing effect on the household is understandable. Oreskes, always a commanding performer, is here given unfortunately little to do, and Ullman and Steele, the latter doubling as several of Alex’s unfortunate passengers, are quite convincing. The marquee draw is Garofalo, and while the actress has clearly worked hard on her accent she seem miscast here and never quite convincing as a tough Russian matriarch. But then again, little about Russian Transport is convincing or, for that matter, transporting.

Acorn Theatre, 410 W. 42nd St. 212-239-6200. www.Telecharge.com. Through March 10.