Category: "Review"

Reviews: Knickerbocker & Cradle and All

May 26th

Two new Off-Broadway comedies demonstrate that the current crop of playwrights is clearly grappling with parenthood issues. Both Jonathan Marc Sherman’s Knickerbocker and Daniel Goldfarb’s Cradle and All deal with impending, possible and actual child-rearing in a manner that suggests genuine anxiety. It’s probably no coincidence that both were written by men.

Knickerbocker, presented as part of the Public Theater’s Public LAB series, depicts the worries of an about-to-be father, 40-year-old Jerry (Alexander Chaplin), who is clearly unsure that he’s up the task. Taking place at the titular restaurant in the East Village, it consists of a series of dining room conversations between the nervous Jerry and various friends and loved ones, nearly all of whom ask the same question: “Are you ready?”

Knickerbocker, presented as part of the Public Theater’s Public LAB series, depicts the worries of an about-to-be father, 40-year-old Jerry (Alexander Chaplin), who is clearly unsure that he’s up the task. Taking place at the titular restaurant in the East Village, it consists of a series of dining room conversations between the nervous Jerry and various friends and loved ones, nearly all of whom ask the same question: “Are you ready?”

Not surprisingly, Jerry’s not at all sure that he is. His beaming wife Pauline (Mia Barron) clearly has no such problem. His friend Melvin (Ben Shenkman), a father himself, tries to assure him with such advice as “It’s all scary, but in a good way.” Meanwhile, his stoner friend Chester (Zak Orth, channeling Zack Galifankis, but in a good way), is aghast. “You’re ruining your life,” he bluntly declares.

Most of these interactions, including Jerry’s emotion-charged conversation with his father (Bob Dishy) who had to raise him alone after Jerry’s mother died when he was a young boy, have a predictable, repetitive feel, as if culled from an episode of The Oprah Winfrey Show devoted to the topic. The only scene that truly throbs with complex vibrancy is Jerry’s reunion with a tart-talking ex-girlfriend (the excellent Christina Kirk), with their alternately flirtatious and baiting interactions subtly revealing the pain of missed opportunities.

Cradle and All literally tries to show both sides of the issue. In the first act, we see a young couple, Clare (Maria Dizzia) and Luke (Greg Keller), vociferously arguing over Clare’s suddenly expressed desire to have a baby after he returns home expecting a quiet evening of sushi (from Nobu, no less) and good wine. The ensuing painful conversation, filled with shattering emotional revelations, threatens to tear the couple apart.

Cradle and All literally tries to show both sides of the issue. In the first act, we see a young couple, Clare (Maria Dizzia) and Luke (Greg Keller), vociferously arguing over Clare’s suddenly expressed desire to have a baby after he returns home expecting a quiet evening of sushi (from Nobu, no less) and good wine. The ensuing painful conversation, filled with shattering emotional revelations, threatens to tear the couple apart.

In Act II we are introduced to the couple in the apartment next door. Played by the same performers, they are Anne and Nate, the harried parents of a newborn who won’t stop crying after being put to bed. Desperate to resolve the problem, they are determined to follow the advice of a how-to parenting book ominously titled “The Extinction Method,” which consists of ignoring the child until it exhausts itself. Their resulting anguish as the long hours pass by is given a sitcom-style comedic treatment, resembling a long lost episode of a post-little Ricky I Love Lucy .

While the writing is largely predictable and formulaic in its blunt presentation of its themes, the evening benefits from a terrific staging by British director Sam Buntrock (Sunday in the Park with George). The set designs by Neil Patel tell the story almost more than the writing itself: Clare and Luke’s Brooklyn Heights apartment is well-appointed and impeccably neat, while Anne and Nate’s is filled with baby paraphernalia, randomly disheveled in the familiar manner that suggests the impossibility of even trying to keep things from getting out of hand.

The sound effects are equally effective. When we hear the anguished cries of the infant emanating from a baby monitor, they sound, as Nate painfully puts it, like those of “a dying animal.”

Although the performers struggle with their characters’ rigid emotional postures in the first act, they blossom in the second, hilariously playing in knockabout fashion such comic highlights as when Anne attempts to physically restrain her increasingly hysterical husband from entering the baby’s room.

Of course, in both of these plays the decks are rather stacked. By the end of Knickerbocker, Jerry, not surprisingly, manages to overcome his insecurities. And the harried new parents in Cradle are far more endearing than the squabbling childless couple. While watching either one, you can practically hear the sound of ticking biological clocks emanating from the audience.

Public Theater, 425 Lafayette St. 212-967-755. www.publictheater.org.

City Center Stage I, 131 W. 55th St. 212-581-1212. www.nycitycenter.org.

Review: By the Way, Meet Vera Stark

May 23rd

Lynn Nottage’s new comedy couldn’t be more different from her last effort, the Pulitzer Prize winning, Rwanda-set Ruined. A satirical portrait of the subservient roles assigned to black performers in 1930s Hollywood--and decades afterwards, for that matter--By the Way, Meet Vera Stark features enough intelligence, wit and insight for two plays, which in fact this one essentially is. While its disparate halves never quite coalesce into a fully satisfying work, there’s still plenty to appreciate.

Sanaa Lathan delivers a standout performance in the title role of an African-American maid to a white movie star (Stephanie J. Block), who is up for the lead role as an octoroon Southern belle in a Gone With the Wind-style Hollywood epic. Vera is anxious to break into the movies as an actress herself, as is her caustic roommate Lottie (Kimberly Herbert Gregory), but the only roles open to them are, well, maids.

The evening’s first half is a screwball comedy ala George S. Kaufman, as Vera deals with her needy employer’s neuroses while working at a dinner party whose guests include a Jewish studio executive (David Garrison) and a pretentious director (Kevin Isola). Also showing up are Vera’s actress friend (Karen Olivo) who’s attempting to pass herself off as a Latina in order to land roles, and a smooth talking chauffeur (Daniel Breaker) with whom Vera’s enjoying a flirtation.

Act II takes a wildly divergent tone. Set four decades later, it revolves around a film symposium dedicated to Vera’s subsequent life and career, hosted by an unctuous intellectual (Breaker). As he and his fellow panelists, including a college professor (Gregory) and an radical poet (Olivo), pontificate about their subject, we see “clips” from a 1973 talk show appearance in which Vera, who went on to become a cheesy Las Vegas headliner, is reunited with her former employer and, as we learn, eventual cinematic co-star.

The evening is fairly bursting with wit, with a particular highlight being the expertly executed mock excerpt from “The Belle of New Orleans,” the film that made Vera a star. And Nottage’s skewering of academic pretensions is so hilariously spot-on that it almost feels like the real thing.

But the play’s satirical ideas, however thoughtful, are ultimately too scattershot and diffuse to sustain this full-length work. The warmth and insightful characterizations on display in the first half devolve into a less satisfying, sketch-like quality in the second.

The production itself is impeccable, from the ingenious staging by Jo Bonney that uses such clever devices as cinematic dissolves for transitions between scenes, to the sets and costumes that hilariously evoke the various periods in which the play is set.

And the acting is superb, from Lathan’s emotionally complex Vera to Block’s hilarious diva to the rest of the ensemble’s wildly divergent dual turns.

Second Stage Theatre, 305 W. 43rd St. 212-246-4422. www.2ST.com.

Review: A Minister's Wife

May 20th

A little show called My Fair Lady provides ample demonstration that the works of George Bernard Shaw are certainly ripe for musical treatment. But the latest attempt, A Minister’s Wife, illustrates the pitfalls as well. This chamber musical adaptation of his 1898 play Candida ironically only serves to detract from the music of his language.

Austin Pendleton has hewed quite faithfully to the original with this condensed adaptation, although he has taken such liberties as removing the character of Candida’s lowbrow father.

But something has definitely been lost in translation. This version lacks the rich humor of Shaw’s play about a minister’s wife (Kate Fry) forced to choose between the affections of the Reverend James Morell (Marc Kudisch), her loving but endlessly distracted husband, and Eugene Marchbanks (Bobby Steggert), the impulsive young poet who has fallen desperately in love with her.

Would that the show sounded as lovely as it looks on Allen Moyer’s gorgeous, beautifully detailed set. But the score, written by Joshua Schmidt (music) and Jan Levy Tranen (lyrics) and performed by a four-piece ensemble, is one of those wan, minimalist affairs that barely makes an impression. It consists less of musical numbers than endlessly talky recitatives that, combined with the soft lighting, ultimately have the effect of lulling the audience into a gentle repose.

Still, the wit and intellectual vigor of Shaw’s play inevitably comes through, and the evening is not without its minor pleasures. They stem mainly from the performances: Fry is both charming and formidable as the sensible Candida who nonetheless finds herself attracted to her inappropriate young suitor; Kudisch movingly conveys both Morell’s moral strength and emotional vulnerability; and Steggert, who sings beautifully here, well captures the delicate balance between Marchbank’s brashness and sensitivity.

The lack of specificity in the title is indicative of the wishy-washy nature of this unnecessary adaptation. A Minister’s Wife may technically qualify as a musical, but it doesn’t exactly sing.

Mitzi E. Newhouse Theater, 150 W. 65th St. 212-239-6200. www.lct.org.

Review: King Lear

May 10th

Most actors play King Lear as an imperial monarch, the better to contrast with the character’s subsequent descent into madness. But in the new production of the play at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, veteran British actor Derek Jacobi (of I, Claudius fame) takes a different approach.

Most actors play King Lear as an imperial monarch, the better to contrast with the character’s subsequent descent into madness. But in the new production of the play at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, veteran British actor Derek Jacobi (of I, Claudius fame) takes a different approach.

His Lear is a loving father in desperate need of his children’s tribute. When it’s denied him by his youngest, favorite daughter Cordelia (Pippa Bennett-Warner), he acts like a spoiled, petulant child. It makes his ensuing despair and humiliation more human and all the more heartbreaking.

His revelatory performance makes it easy to see why BAM imported this Donmar Warehouse revival when productions of this theatrical warhorse are positively ubiquitous. Indeed, there are two more arriving later this year; one courtesy of the Royal Shakespeare Company and another at the Public Theater starring Sam Waterston.

As has become standard in modern Shakespearean productions, this staging is a decidedly minimalist affair, performed on a bare stage composed of whitewashed wooden planks.

But that doesn’t stop director Michael Grandage from providing thrilling theatrical touches, most notably in the powerful storm scene in which lighting and sound effects are employed to harrowing effect.

But even then, it’s Jacobi’s unconventional acting choices that make the most impact. Rather than shouting his lines—most famously “Blow, winds, and crack your cheeks”--with the customary full volume, he whispers them, making us strain to hear this fallen monarch while he’s at his most vulnerable.

The actor is ably supported by the terrific ensemble, with particularly strong turns by Gina McKee and Justine Mitchell, chillingly low-key as the treacherous Goneril and Regan; Alec Newman, impressively villainous as the aggrieved Edmund, and Paul Jesson, heartbreakingly moving as the wronged Gloucester. Best of all is Ron Cook’s trenchant Fool who acerbically comments on the surrounding chaos.

The production admirably downplays the melodramatic bombast that afflicts so many current interpretations while restoring the play to its tragic psychological dimensions. Jacobi’s Lear is less a fallen monarch than an elderly parent desperately struggling to cope with the physical and mental infirmities accompanying old age.

BAM Harvey Theater, 651 Fulton St., Brooklyn. 718-636-4100. www.bam.org.

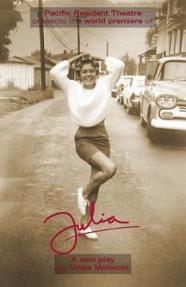

Review: Julia

May 9th

That life doesn’t always offer the opportunity to neatly right past wrongs is a promising theme for a drama. Too bad, then, that Julia squanders it.

The central character is Lou, a clearly ill man in his seventies who wanders into a rundown coffee shop. It’s soon revealed that he’s returned to his hometown to make amends to Julia, the girl he loved decades earlier and never saw again after he served in the Korean War. Her son refuses to have him upset his mother, now suffering from dementia in a nursing home. But when Lou literally gets on his knees and begs, he relents.

It’s here that the evening turns anti-climactic. A flashback to the fateful encounter between the younger Lou and Julia reveals immature anger but hardly the sort of behavior that would haunt someone for the rest of his life.

And when Lou is finally reunited with his former flame who doesn’t recognize him, the most dramatic moment centers around the pair eating snack cakes.

The acting, however, couldn’t be better. Richard Fancy, a familiar face from stage and screen (Being John Malkovich, Seinfeld), is deeply affecting as Lou, and Roses Prichard beautifully captures the confused daze of an Alzheimer’s sufferer.

59E. 59 Theaters, 59 E. 59th St. 212-279-4200. www.59e59.org