Category: "Review"

Review: Barrymore in Toronto

Mar 1st

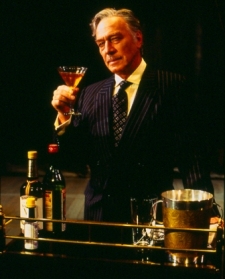

Lucky Toronto audiences are currently being given the opportunity to witness Christopher Plummer reprising his virtually one-man-show Barrymore, about the famed matinee idol who was as famed for his drinking and debauchery as his stage and film performances. Returning to the role that garnered him a Best Actor Tony Award in 1997, the now 81-year-old performer belies his age—he’s playing Barrymore at age 60, shortly before the end of his life—in a still magnificent star turn that loses none of its impact in the elegant but cavernous Elgin Theatre.

There’s nothing particularly original about William Luce’s slight drama, which utilizes the same biographical formula he employed to greater effect in The Belle of Amherst and with more lackluster results in such later works as Lucifer’s Child (about Isak Dinesen) and Lillian (Lillian Hellman). Set on a mostly bare stage littered with props and costumes, it depicts the dissipated acting legend preparing for a possible stage comeback in one of his greatest successes, Richard III.

Frequently aided by a frustrated offstage prompter, Frank (John Plumpis), the alcohol-ravaged Barrymore tenuously attempts to recite his mostly forgotten lines, frequently dipping into such other Shakespearean roles as Hamlet along the way.

But he mainly regales the audience with a rambling account of his life and career, punctuated by jokey one-liners (“Divorce costs more than marriages, but damn it, they’re worth it!”) and frequent nips from a handy liquor bottle.

Using his glorious voice and still lithe physicality to excellent effect, Plummer well conjures his subject’s charisma and magnetism while also poignantly revealing the vulnerability underlying his comic bravado.

It’s essentially a glorified stand-up routine, but it’s also such a wonderful vehicle that it seems totally understandable that the actor would want to bring it back for his loyal Canadian fans. The production is also scheduled to be filmed for broadcast to movie theaters throughout that country.

Elgin and Winter Garden Theatre Centre, 189 Yonge St., Toronto. 416-872-5555. www.ticketmaster.ca.

Review: Diary of a Madman

Feb 25th

As he’s demonstrated in such films as Shine and the recent Broadway production of Ionesco’s Exit the King, there are few actors as adept at playing crazy characters as Geoffrey Rush. Now starring in the titular role in The Diary of a Madman, the performer delivers an inspired tour-de-force turn that plays like a demented vaudeville act.

Set in 19th century St. Petersburg, the piece depicts the lapse into psychosis of Aksentii Ivanovich Poprishchin, a low-level, pencil-pushing bureaucrat endlessly frustrated by the drudgery of his demeaning job. At night he retreats to the safety of his attic garret, where he pours out his increasingly bizarre fantasies into his journal. In between his exhausting exhortations, he’s attended to by his solicitous Finnish housekeeper (Yael Stone).

Decrying the dictatorial demands of his boss and indulging in his fantasies of an imagined love affair between him and the office director’s beautiful daughter, he regales us with such fantasies as the supposed dialogue between two neighborhood dogs and his dawning realization that he’s actually the king of Spain.

This production, which originated more than two decades ago at Sydney’s Belvoir theater company, is less effective as a dramatization of Gogol’s classic 1835 short story than as a vehicle for its star’s protean talents. Sporting a bizarre tuft of garish red hair and increasingly outlandish costumes, Rush delivers an endlessly physical performance in which his extreme bodily contortions provide a visual correlative to his character’s over-the-top rantings.

While the performance is certainly entertaining, neither it nor the dramatization—by David Holman, director Neil Armfield and Rush himself—ultimately cuts very deep. Although highly effective in conveying the comic extremities of the character’s eccentricities, it is far less so in its attempt to harrowingly depict his full-blown descent into madness.

Adding mightily to the show’s impact are its superb technical elements, including Catherine Martin’s set design with its blood red walls and claustrophobic green ceiling; Mark Shelton’s haunting lighting, which creates shadows that seem to take on a life of their own; and the evocative sound effects and music, created by a pair of musicians located at the side of the stage.

It’s a marvelous showcase, to be sure, for this supremely talented actor, Oscar nominated for his far more down-to-earth performance in the hit film The King’s Speech. But the production’s effects are all on the surface; at the end, we care far too little about this tragic figure, despite the undeniable laughs he’s provided along the way.

BAM Harvey Theater, 651 Fulton St., Brooklyn. 718-636-4100. Through Mar. 12.

Review: Interviewing the Audience

Feb 17th

Everybody has a story, but some are more interesting than others. So you take your chances with Zach Helm’s Interviewing the Audience, currently at the Vineyard Theatre. Based on a concept created by the late Spalding Gray, this theater piece is akin to tuning in to a random episode of Dr. Phil.

Everybody has a story, but some are more interesting than others. So you take your chances with Zach Helm’s Interviewing the Audience, currently at the Vineyard Theatre. Based on a concept created by the late Spalding Gray, this theater piece is akin to tuning in to a random episode of Dr. Phil.

In this theatrical exercise, Helm--the screenwriter of Stranger Than Fiction and Mr. Magorium’s Wonder Emporium (he also directed the latter)—randomly selects audience members and brings them onstage for impromptu chats. Since every performance will be entirely different, the results are inevitably varied.

At the show caught, the subjects included a pathologically shy 16-year-old who confessed to seeing a therapist for her social anxiety; a Brazilian college student visiting the U.S.A.; and an older woman who talked at length about her relationship with her daughter living in Colorado.

The unassuming Helm, who thankfully takes no for an answer should you choose to decline his invitation—“We have a lot of voyeurs here tonight,” he commented upon seeing the large number of hands raised by those who didn’t wish to participate—takes an almost therapeutic approach to his gentle interrogations. Unlike Gray, who added a layer of irony to his questioning, he projects an attitude of sincere caring.

He begins each talk with the same question, “How is it that you came to be at the theater?” After that, he wings it, although he frequently finds interest in articles of clothes the person is wearing. In the case of the withdrawn teen, who came to the stage wearing a wolf’s head hat, complete with ears, that nearly covered her entire face, it provided plenty of fodder for conversation.

There is certainly something gripping about people suddenly opening up about their lives in front of a large group of strangers, and the solicitude expressed by Helm was frequently touching. He adds a personal level to the proceedings by frequently revealing intimate details about his own life.

Since none of the three women at the performance caught were particularly interesting or articulate—the Brazilian warned up front that her English language skills were lacking—the results were somewhat less than compelling. But in a spontaneous atmosphere such as this, lightning is bound to strike, so your experience may be far different. As much social experiment as it is theater, Interviewing the Audience is a slight but undeniably fascinating experience.

Vineyard Theatre, 108 E. 15th St. 212-353-0303. Through Feb. 27.

Review: Black Tie

Feb 11th

Few playwrights have covered a particular social milieu as exhaustively and effectively as A.R. Gurney. For decades now, he has been steadily producing comedies dealing with the social mores of the WASP set, with often sublime results (The Dining Room, The Cocktail Hour). His latest effort, Black Tie, being given its world premiere by Primary Stages, is a decidedly lesser, more trivial entry in his increasingly growing canon. But thanks to some typically sharp comedic writing and a well-acted production expertly staged by Mark Lamos, it is nonetheless often amusing.

The primary dilemma facing father of the groom Curtis (Gregg Edelman) is the choice of attire for his son’s impending nuptials. He wants to wear the vintage tuxedo passed down by his late father, but the idea seems rather silly since the decidedly casual affair is taking place at a well-worn, rustic hotel in the Adirondacks (perfectly depicted in John Arnone’s detailed set).

Just as he’s trying on the newly tailored duds and nervously contemplating the speech he’s due to give at the rehearsal dinner, who should appear but the dearly departed father himself (Daniel Davis). As Curtis interacts with his exasperated wife Mimi (Carolyn McCormick), his sassy teen-age daughter Elsie (Elvy Yost) and his anxious son Teddy (Ari Brand), his father, unseen and unheard by everyone but Curtis, hovers over the proceedings, offering his own old-fashioned, bemused take on things.

Although the situations the playwright has devised often border on silliness—for instance, a mini-crisis erupts when the bride’s old boyfriend, now an in-your-face stand-up comic, threatens to hijack the dinner by performing his entire act—the play offers enough incisively observed commentary on the culture clash between the younger and older generations and amusing one-liners to compensate for the hoary plot schematics.

The lead actors play their roles to perfection. Edelman hits just the right notes as the beleaguered father; the perfectly cast McCormick is both elegant and funny as the exasperated wife; and Davis is wonderfully droll as the spectral figure who insists that his son is not donning a tuxedo but rather a “dinner jacket.”

59E. 59 Theaters, 59 E. 59th St. 212-279-4200. www.primarystages.org.

Review: Three Sisters

Feb 9th

For all their staying power over the years, the plays of Anton Chekhov are remarkably fragile works in performance. It’s so rare that all the elements come together--that all of the performers work in synch, that the directorial tone is cohesive—that more often than not contemporary productions are a trial to sit through.

The Classic Stage Company’s revival of Three Sisters is a case in point. Although it contains many admirable elements, including several worthwhile performances and a striking set design, it never coheres into a satisfying whole. There are stirring moments, but the general unevenness is ultimately defeating.

Director Austin Pendleton, who staged a 2009 production of Uncle Vanya at the same theater, has reunited several of its cast members for this effort, most notably the starry married duo of Maggie Gyllenhaal and Peter Sarsgaard.

The titular siblings so famously longing to return to Moscow are played here by Gyllenhall as Masha, trapped in a loveless marriage; Jessica Hecht as Olga, the spinster schoolteacher; and Juliet Rylance as the idealistic youngest sister, Irina.

The supporting cast is no less impressive. Besides Sarsgaard as the military officer who becomes the object of Masha’s ill-fated obsession, there are Josh Hamilton as the sisters’ unhappy brother Andrey; Marin Ireland as Natasha, his shrewish wife; and Paul Lazar as Masha’s much older husband. Smaller roles are filled out by such theater veterans as Roberta Maxwell, George Morfogen and Louis Zorich.

As with the Vanya, Gyllenhaal and Sarsgaard are again the weakest links here, delivering listless performances that rarely delve beneath the surface. Faring much better are Hecht, who infuses Olga with a poetic intensity, and Rylance, utterly radiant.

The supporting turns are similarly uneven. Hamilton is quite moving as the forlorn brother, for instance, while the wildly gesticulating Ireland seems in another, far more modern, play entirely.

Paul Schmidt’s translation, while undeniably accessible, is also problematic, filled with jarring slang that feels inappropriate for the period.

Kudos, however, to set designer Walt Spangler, who use the CSC’s awkward space to excellent effect. The playing area is dominated by a massive dining table fully ornamented for a lavish feast, providing an apropos visual correlative to the sisters’ regimented lives. When the table is lifted via pulleys to provide an open space for the final act set in a courtyard, it feels positively liberating.

Classic Stage Company, 136 E. 13th St. 212-352-3101. www.classicstage.org.