Review: Dogfight

Jul 17th

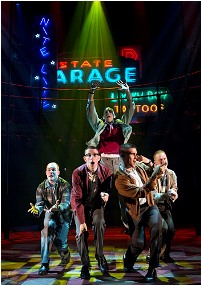

Much like the 1991 film that inspired it, the new musical Dogfight is a sweet, unassuming and quietly touching tale that has the feel of a tightly constructed short story. While its storyline about a young Marine and the plain young woman he first exploits and then falls for doesn’t particularly benefit from musicalization, book writer Peter Duchan and composers Benj Pasek and Justin Paul have done an admirable job of capturing its appeal. This small-scale musical could well become a staple at regional theaters.

Told mostly as flashback and set on in San Francisco on the eve of the1963 Kennedy assassination—a date that has become dramatic shorthand for lost innocence—it concerns a malicious contest held by a trio of young Marines the night before they are scheduled to be deployed to Vietnam. The goal is to secure a date with the ugliest woman, or dog, they can find, with the soldier procuring the most objectionable one winning the prize.

Corporal Eddie Birdlace (Derek Klena) thinks he’s found his winner, meaning a loser, in Rose (Lindsay Mendez), a sweet but plain woman who works as a waitress in her mother’s modest diner. Wooing her by falsely professing a shared love of folk music, he persuades her to accompany him to a party attended by his fellow conspirators.

When Rose becomes aware of the scam thanks to the loose-lipped female accomplice (Annaleigh Ashford) of one of the Marines who’s stacked the decks, she naturally reacts with deep anger and hurt, even telling Eddie that she hopes he dies overseas. But by then he’s fallen for her, and his attempts to make amends lead to a tentative romance even though his idea of an apology is to tell her, “I don’t care what you look like.”

With its tuneful musical score blending sixties-style pop/rock, tender ballads and more sophisticated, Sondheim-influenced songs, the show feels like a bit of a hodgepodge. Such early exuberant numbers as “Some Kinda Time,” featuring energetic choreography by Christopher Gattelli that recalls his Tony Award-winning work for Newsies, at first give the impression that the show is going to sacrifice subtle emotion for bombast. But under the assured direction of Joe Mantello it soon settles down into a more relaxed groove, with such scenes as the couple’s awkward first date at a swanky restaurant proving thoroughly winning.

Much of the credit goes to the two young leads. While he has the unenviable task of trying of match the soulfulness of the film’s River Phoenix, the strong-voiced Klena makes the role his own, and is completely credible as an unsophisticated young soldier who taps into his innate decency. And Mendez, although hardly as unattractive as her character is supposed to be, conveys awkwardness and insecurity in deeply touching fashion.

They’re well supported by the rest of the ensemble, with particularly strong work by Josh Segarra (Lysistrata Jones) and Nick Blaemire as Eddie’s fellow Marines and Ashford as the contestant who spills the beans.

Second Stage Theatre, 305 W. 43rd St. 212-246-4422. www.2st.com

Review: As You Like It

Jun 22nd

It’s debatable whether the world needed yet another As You Like It, since Shakespeare’s pastoral romantic comedy seems to receive a new production every other week. But there’s no debating that the current rendition in Central Park fully mines the joyous aspects of this hardly neglected work. Beautifully staged by Daniel Sullivan and performed by a talented ensemble featuring the increasingly impressive Lily Rabe, it piles on the riches with a tunefully foot-stomping bluegrass score by none other than Steve Martin. It’s an early midsummer night’s dream.

Although the play’s silly plot machinations have a tendency to wear thin, they seem far less contrived in this charming outdoor production that takes full advantage of its bucolic setting. By the time characters start miraculously popping up amidst the branches of the tall trees dotting John Lee Beatty’s evocative Arden Forest set, you’ll be thoroughly hooked.

The action has been transposed to the 19th century rural American South, which not only works in terms of the play’s raucous humor but also provides the opportunity for the joyful musical interludes provided by a raucous four-piece band featuring the terrific Tony Trischka on banjo.

Sullivan, who staged a similarly masterful Merchant of Venice at the same venue, delivers a remarkably cohesive production that includes no weak links among the performers. Rabe, who, despite her attractiveness, is remarkably convincing when assuming a male identity, is a sparkling Rosalind and displays terrific romantic chemistry with David Furr’s Orlando.

Andre Braugher strikes just the right respective notes of oppressive authority and gentle kindness in his dual roles as Duke Frederick and Duke Senior; Oliver Platt is a hilariously boisterous Touchstone, with Donna Lynne Champlin more than his match as his love interest; Stephen Spinella impressively delivers the philosopher Jacques’ famous “7 Ages of Man” speech; Renee Elise Goldsberry is appealing as the sensible Celia; and the appropriately named Will Rogers is a hoot as the lovestruck shepherd Silvius. Even the smaller roles are played by such solid pros as Robert Joy, Omar Metwally, Macintyre Dixon and Jon DeVries.

The Delacorte Theater is celebrating its 50th anniversary with this buoyant production, to be followed later this summer by the musical Into the Woods. You only have another week to catch it, but make the effort. It’s even worth braving the heat.

Delacorte Theater, Central Park. 212-967-7555. www.publictheater.org. Through June 30.

Review: Uncle Vanya

Jun 18th

There’s one thing that can be definitely said about the Soho Rep’s production of Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya: You’ll probably never again feel so closely involved with its characters.

That’s because they’re literally at arm’s length in this revival adapted by Annie Baker and directed by Sam Gold, who previously collaborated on the playwright’s Circle Mirror Transformation and The Aliens. With audience members sitting on risers surrounding the action in the tiny theater space, there is an unmatched intimacy to the proceedings.

That’s the chief novelty of this rendition which proves largely faithful to the original. Although the set and costumes are contemporary, the play has not otherwise been updated, and the language, while peppered here and there with contemporary phrases, is not particularly jarring.

The results play somewhat as if we’ve been invited to a private rehearsal. And much of it works very well indeed, especially when it comes to the work’s considerable humor. Chekhov’s iconic characters have never seemed as pathetically silly as they do here, presented at uncomfortably close range.

(Speaking of uncomfortable, you may want to schedule a chiropractic appointment immediately after the show, since the confined seating means that some audience members spend nearly three hours with their legs tightly crossed. That, or risk kicking the person in front of you in the head.)

A first-rate cast has been assembled for this limited run, the first six weeks of which are already sold out. The superb Reed Birney plays Vanya; Peter Friedman is the blustery professor; Maria Dizzia is his sexy young wife, Yelena; Merrit Weaver, currently a regular on TV’s Nurse Jackie, is the desperately lovesick Sonya; and Michael Shannon is the distracted Astrov, the doctor who is the object of her affections. Even such smaller roles as the matriarch Maria and the nanny Marina are played by such old pros as Rebecca Schull and Georgia Engel respectively.

Still, despite the fine efforts of everyone involved—adding to the put-on-a-show vibe, playwright Baker even did the costume designing—there’s nothing particularly revelatory about this Vanya save for its closeness, which inevitably starts to wear thin after a while. The opening scenes, with the actors bustling all around you, are extremely involving. But the late-night encounter between Yelena and Sonya, performed in near total darkness and staged as if we’re overhearing a private conversation, has a near soporific effect.

The performances are mostly faultless. Birney’s Vanya is both amusing and unsettling; Shannon brings his expert brand of neurotic intensity to the troubled doctor; the gorgeous Dizzia is so dazzlingly sexy as Yelena that Astrov’s obsession with her is totally believable; and Weaver is deeply moving as the woeful Sonya. The supporting turns are equally expert, with Matthew Maher particularly hilarious as the impoverished landowner disparagingly referred to as “Waffles.”

This Vanya, although certainly unique, is by no means revelatory, and may well be eclipsed by the acclaimed version starring Cate Blanchett arriving here later this summer. But there’s no denying the intense commitment of its cast and creative team, and will prove a memorable experience for those fortunate few able to snag tickets.

Soho Rep, 46 Walker St. 212-352-3101. www.sohorep.org. Through July 22.

Review: Harvey

Jun 14th

Jim Parsons works magic in the Roundabout Theatre Company’s revival of Harvey. I had my doubts that this old chestnut would have much impact these days. But Mary Chase’s 1944 comedy, which won the Pulitzer Prize and enjoyed 1,775 Broadway performances in its original run, sparkles anew thanks to this talented actor’s ineffable charms.

He certainly had tough competition from Jimmy Stewart, whose performance is immortalized in the classic 1950 film version. But the Emmy-winning star of The Big Bang Theory manages to make the part his own and then some--no small feat.

The play, which hasn’t been seen on the Great White Way since a 1970 production starring Stewart and Helen Hayes, concerns Elwood P. Down, an exceedingly courtly, mild-mannered man who happens to have a particular eccentricity. His constant companion is the title character, a 6’3” white rabbit who no one else seems able to see.

The situation naturally concerns his family, including his sister Vera (Jessica Hecht) and niece Myrtle (Tracee Chimo). But when Vera attempts to have her brother committed to a sanitarium, she’s the one who’s mistakenly committed instead of him.

Naturally, this leads to all sorts of complications, especially since Elwood charms the bejeesus out of everyone with whom he comes into contact. And, judging by the doors opened and pages turned by the invisible creature who Elwood describes as a “pooka,” he may not be so imaginary after all.

But when things are eventually straightened out and Elwood is about to receive an injection that will forever rob him of his delusions, Vera is forced to decide whether that’s such a good thing after all.

The play’s theme of carefree insanity versus reality’s hard truths has since been echoed in any number of works, including A Thousand Clowns and One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. But it still has a resonant poignancy that is beautifully captured in director Scott Ellis’ moving and funny production.

That it succeeds to the extent that it does is largely due to its star, who delivers a portrayal that is only comparable to his Big Bang character in its off-the-wall quirkiness. But unlike the obliviously obnoxious Sheldon, his Harvey is so charming that he immediately wins the audience over. There was no doubt about Parsons’ chops and perfect comedic timing, but his ability to so effortlessly shift gears here, not to mention seem perfectly credible for the period, is a revelation.

He’s well supported by the excellent supporting cast, which also includes such veterans as Charles Kimbrough as an increasingly flustered psychiatrist and Carol Kane as his wife. Rich Sommer also scores big laughs with his blustery turn as a sanitarium attendant resistant to Elwood’s charms.

But it’s Parsons who carries the revival on his shoulders, and he succeeds magnificently. But evening’s end, you’re likely to find yourself seeing an invisible white rabbit as well.

Studio 54, 254 W. 54th St. 212-719-1300. www.roundabouttheatre.org. Through Aug. 5.

Review: Rapture, Blister, Burn

Jun 13th

It’s appropriate that Gina Gionfriddo’s new play has been compared favorably to Wendy Wasserstein’s The Heidi Chronicles. Like that groundbreaking work, this delicious comedy interweaves personal and social issues in a way that is both entertaining and thoughtful. Receiving a beautifully acted and staged world premiere production at Playwrights Horizons, Rapture, Blister, Burn looks to have a long theatrical life.

This work offers a sort of Prince and the Pauper twist to its themes of gender politics. It concerns two former college friends reuniting after many years who have taken vastly different life paths: Catherine (Amy Brenneman) has a successful and lucrative career as a feminist author who has written popular tomes analyzing pornography and horror films, while Gwen (Kellie Overbey) is a wife and mother of two young children.

Further complicating the emotional dynamics is the fact that Gwen is married to Catherine’s college sweetheart Don (Lee Tergesen), an underachieving dean at a small New England college who mainly spends his time smoking pot and watching porn.

Watching from the sidelines are Catherine’s elderly mother Alice (Beth Dixon), who has just suffered a heart attack, and Gwen’s 21-year-old babysitter Avery (Virginia Kull), sporting a nasty black-eye from an altercation during an ill-conceived TV reality show project with her filmmaker boyfriend.

The play is structured around a series of seminar sessions about feminist issues taught by Catherine and attended by Gwen and Avery, with Alice hovering in the background. The three generations of women comically weigh in on such issues as torture porn and the anti-feminist philosophies of Phyllis Schlafly.

But it’s when Catherine and Don impulsively resume their romance that the play truly takes off. Both women, who have always been envious of the other’s lifestyles, agree to trade lives. Gwen, with her teenage son in tow, goes off to live in Catherine’s Manhattan apartment and pursue a graduate degree, while Catherine stays in New England to enjoy booze-fueled, all-night movie marathons with Don.

While the play isn’t always credible in its contrived set-ups, it works beautifully nonetheless, thanks to its nuanced characterizations and sparkling dialogue that is practically Shavian in its wit.

“I am ready and willing to embrace mediocrity and ambivalence, you’re just not letting me,” cries Catherine when Don finds himself unhappy in the new arrangement.

Under the superb direction of Peter DeBois, who performed similarly expert chores for the playwright’s Pulitzer Prize-nominated Becky Shaw, the cast shines. Brenneman superbly conveys Catherine’s angst-ridden contradictions; Overbey brings complex shadings to her role as the unhappy wife; Tergesen is hugely appealing as the wastrel lover; Kull is a riot as the perky young modern woman; and Dixon is slyly funny as the elderly mother who missed out on the feminist liberation movement.

Plays that manage to mix genuine feeling and provocative ideas are all too rare. It’s all the more reason to appreciate what this talented young playwright has wrought.

Playwrights Horizons, 416 W. 42nd St. 212-279-4200. www.TicketCentral.org. Through June 24.