Review: Jesus Christ Superstar

Mar 23rd

Jesus Christ Superstar, which began its life as a concept album, has always been more fun to listen to than actually watch. But the new Broadway revival--imported from the Stratford Shakespeare Festival by way of the La Jolla Playhouse—is a galvanizing rendition that grips from first moment to last. Staged in propulsive fashion by Des McAnuff, who has no small experience with this sort of material (Jersey Boys, The Who’s Tommy), the production is something to shout hallelujah about.

Short of the bloated, high-concept gimmickry that afflicted the show’s last Broadway outing, this is a lean and mean, stripped-down version that eschews camp. It concentrates appropriately and thrillingly on the sung-through pop/rock score by Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice which is more and more beginning to seem their best.

There’s an appropriate pre-show announcement that gets a laugh. It informs people to feel free to open their wrapped hard candies at any point, since the music will drown out the sound. And so it does under Rick Fox’s musical direction, which features both the volume and the high energy to put across the score with maximum impact. Steve Canyon Kennedy’s sound design, which at several points employs surround-sound effects that have audience members swiveling in their seats, is another plus.

The action is staged on a simple set (designed by Robert Brill) that largely consists of metal scaffolding; movable stairways and ladders; and ticker-tape style LCD displays. It’s a cliché, sure, but it works perfectly here, keeping the focus on the actors and instilling the proceedings with a suitably timeless feel.

The performers infuse their vocals with a powerful urgency, and their acting is impressive as well. Paul Nolan is an intriguingly ambiguous, complex Jesus; Chilina Kennedy a sympathetic and appealing Mary Magdalene; and Tom Hewitt a properly sinister but not cartoonishly villainous Pontius Pilate. At the reviewed performance, understudy Jeremy Kushnier played Judas (filling in for Josh Young), but there was absolutely no tentativeness evident in his riveting, dynamically sung portrayal.

Also terrific are Bruce Dow, bringing a welcome edge to the usually comic King Herod, and Marcus Nance, whose deep-voiced Caiaphas is spine-tingling.

Lisa Shriver’s energetic choreography keeps the proceedings moving at a fever pitch, while McAnuff’s uncommonly lucid staging is consistently striking, especially in the climactic Crucifixion sequence in which Judas returns as a shiny-suited, Evangelical-style preacher.

To quote one of the show’s more memorable numbers, “Hosanna” to this revival which stirs the sort of excitement that must have been felt upon its 1971 Broadway premiere.

Neil Simon Theatre, 250 W. 52nd St. 877-250-2929. www.ticketmaster.com.

Review: Death of a Salesman

Mar 16th

Whenever there’s a new revival of Death of a Salesman people marvel at the fact that it seems so newly relevant. But it’s not that society is changing but rather that Arthur Miller’s 1949 masterpiece, now receiving a triumphant Broadway production directed by Mike Nichols, is so timeless.

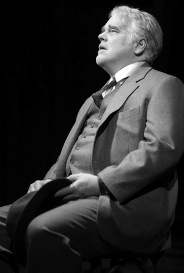

There was some question about the necessity for this revival, coming relatively soon after the acclaimed 1999 production starring Brian Dennehy. And the casting of 44-year-old Philip Seymour Hoffman as the 62-year-old Willy Loman seemed dubious, despite the fact that the play’s original star, Lee J. Cobb, was a mere 37 when he essayed the role.

But any doubts are immediately erased by this shattering revival, which marks a major return to form for its legendary director after his disappointing production of The Country Girl a few years back.

The play itself is nearly indestructible, with Miller’s groundbreaking combination of harsh naturalism and poetic illusion registering as powerfully today as it did upon its premiere. And this production harkens back to the original in significant ways, reprising the original groundbreaking set design by Jo Mielziner as well as the haunting background music by Alex North, who would go on to write the scores for such films as A Streetcar Named Desire, Spartacus and dozens of others.

Mielziner’s set, comprised of the skeleton of the Loman’s Brooklyn home and a minimum of props, skillfully allows for the use of lighting and projections to infuse the proceedings with a dreamlike, cinematic feel that conveys Willy’s flights between reality and fantasy, the past and the present. Seeing it come to life feels like a trip into theatrical history.

From the opening moment--when Hoffman’s lumbering Willy wearily drops his sample cases onto the kitchen floor--to the shattering final scene in the graveyard, Nichols’ production doesn’t make a single false step.

Hoffman, whose ample physique makes him appear older than he is, is a shattering Willy, perhaps the most vulnerable ever. Unlike Dustin Hoffman, who projected a bantamweight feistiness, and Dennehy, with his intimitading physical presence, his Willy is a relentlessly pitiful, tragic figure. But the actor also beautifully captures the humor of the role--the way that Willy’s quick-silver contradictions reflect not just his crumbling mind but also his stubbornly self-defeating personality.

Linda Emond, also playing older than she is, is deeply moving as the wife, Linda, investing even the character’s most familiar speeches with fresh emotional immediacy. British actor Andrew Garfield, making his Broadway debut after wowing film audiences in The Social Network (and just prior to his taking over for Tobey Maguire in the Spider-Man film reboot), is superb as the oldest son Biff, whose emotional self-realization at the end of the play is its pivotal scene. And unlike many English actors playing New Yorkers, he thankfully doesn’t overdo his accent.

Everyone in the supporting cast is sublime: Fran Wittrock, joyfully energetic as Happy, the other “Adonis son”; Bill Camp, beautifully understated as Charley, the best friend who offers Willy a lifeline that the proud salesman refuses to accept; John Glover, floridly melodramatic as Ben, Willy’s brother who haunts him with the misery of missed opportunities; and Fran Krinz, versatile as Bernard, the nerd who grows up to be lawyer appearing before the Supreme Court.

Yes, you’ve seen Salesman before. And the play is definitely not light-hearted entertainment (although it does feature surprisingly humorous moments). But when a production this well acted and staged comes along, attention must be paid.

Ethel Barrymore Theatre, 243 W.47th St. 212-239-6200. www.Telecharge.com. Through June 2.

Review: An Iliad

Mar 9th

The simple act of storytelling is a time-honored theatrical tradition. But it can also a hackneyed one. Case in point: An Iliad, the new one-man show—well, technically two man, but more on that later—based on the poem by Homer as translated by Robert Fagles. This epic tale of the Trojan War has been rendered into a chatty, meandering monologue delivered by a character only known as “The Poet.” He’s accompanied with music by an onstage bassist providing the appropriate emotional cues.

This piece being presented by the New York Theatre Workshop was adapted by actor Denis O’Hare and playwright Lisa Peterson (Light Shining in Buckinghamshire, Slavs), with the latter also directing. Theatergoers are being enticed to see the production not once but twice, since O’Hare is alternating in the role with Stephen Spinella.

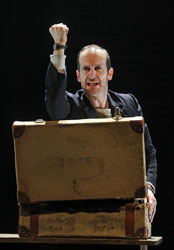

Although I’m a dedicated theatergoer, even the prospect of comparing two such talented actors wasn’t enough to induce me to sit through the 100-minute monologue a second time. I chose to see O’Hare since he was also the co-author.

The actor, clad in a shabby overcoat and toting a suitcase, wanders onto the stage like a character in a Beckett play and begins chanting in Greek. But he quickly resorts to mostly colloquial language, providing an abridged version of the story that concentrates on the Greek warrior Achilles and his Trojan counterpart Hector.

Unless you’re familiar with the complicated story--much of which has admittedly slipped from my memory since college days—the proceedings are apt to prove somewhat confusing. But not to worry, since the message of the piece is, gasp, war is bad, and its continued relevance is hammered home in a recitation of a litany of modern-day conflicts.

The normally mesmerizing O’Hare recites the text in a world-weary monotone that quickly proves tedious. And although the expert lighting and sound design provide evocative underpinnings, they’re not enough to give the piece sufficient theatricality. For all its obvious good intentions, it ultimately has the feel of a self-indulgent stunt.

New York Theatre Workshop, 79 E. 4th St. 212-279-4200. www.ticketcentral.com. Through March 25.

Review: The Lady From Dubuque

Mar 7th

Not that I’m in any rush, but whenever death comes for me I hope it takes the form of the Lady from Dubuque.

As elegantly personified by Jane Alexander in the Signature Theatre’s revival of Edward Albee’s haunting play being presented under the possessory moniker of Edward Albee’s The Lady From Dubuque, death is a highly comforting presence.

The Signature is well fulfilling its mandate by resurrecting this rarely seen work, which lasted a mere twelve performances upon its 1980 Broadway premiere. But while it received a critical drubbing at a time when the playwright was in a definite career slump, this revival strongly makes the case that--while not one of Albee’s major works—it definitely deserves reconsideration.

It begins in a fashion recalling his classic Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, with three couples engaged in a party game in a well-appointed suburban home which, like the domestic battleground in God of Carnage, is decorated with African tribal art.

The game is 20 Questions, which is never conducive to peace and harmony but does lead one of the characters to ask the existential question, “Who am I?” The participants include hosts Sam (Michael Hayden) and his wife Jo (Laila Robins); next-door neighbors Edgar (Thomas Jay Ryan) and Lucinda (Catherine Curtin); and Sam’s best friend, Fred (C.J. Wilson) and his latest, younger girlfriend Carol (Tricia Paoluccio).

It soon becomes apparent that Jo is ill--terminally ill in fact--and is subject to bouts of horrific pain. The gathering thus ends early, but not before the arrival, just before the first act curtain, of a beautifully dressed older woman (Alexander) and her dapper African-American companion (Peter Francis James).

When a bleary-eyed Sam stumbles upon them the following morning, he’s more than a little discomfited, especially since the “Lady from Dubuque” claims to be Jo’s mother. Meanwhile, her cohort, Oscar, proves to be a rather menacing figure, mocking the confused Sam and adopting an exaggerated shuffle and dialect when his race is pointed out.

The rather contrived return of the previous evening’s guests creates further conflict, with Sam eventually being rendered unconscious by Oscar via a Vulcan-like nerve pinching. But when a clearly agonized Jo eventually makes her way downstairs, she immediately takes comfort in the presence of her female visitor, who embraces her like the mother she pretends to be.

Although the play is not exactly subtle in its allegorical conceit of death, it nonetheless exerts an undeniable fascination thanks to Albee’s gift for blending nasty humor, poignant drama and cosmic ideas in compelling fashion.

This revival staged by David Esbjornson expertly mines the work’s elemental power, and is beautifully acted by the ensemble. Although anyone who saw the original production could never forget the thrilling performances by Irene Worth and Earle Hyman as the mysterious visitors, Alexander and Frances James are superb successors, with the latter entertainingly mining his character’s droll humor.

After this successful resuscitation, more exploration of the Albee canon is clearly warranted. One can hardly wait to see what this adventurous company might do with the notorious 1983 flop, The Man Who Had Three Arms.

Pershing Square Signature Center, 480 W. 42nd St. 212-244-7529. www.signaturetheatre.org. Through April 15.

Review: Tribes

Mar 5th

On its surface, Tribes is concerned with a young deaf man’s sudden decision to embrace sign language rather than rely on lip-reading. But that description doesn’t do justice to Nina Raine’s compassionate drama, which premiered at London’s Royal Court and is now receiving an outstanding off-Broadway production directed by David Cromer.

The play revolves around a British family that includes: highly opinionated academic and patriarch, Christopher (Jeff Perry); his peacemaking wife Beth (Mare Winningham); emotionally fragile son Daniel (Will Brill); daughter Ruth (Gayle Rankin), a self-deluded, aspiring singer; and deaf son Billy (Russell Harvard, who is hearing-impaired in real life).

The clan exults in their loud, vociferous arguments around the dinner table, in which Billy can only partially be involved. But that’s fine with him, until he meets Sylvia (Susan Pourfar), with whom he’s immediately smitten. Unlike him, she’s well versed in signing, since she’s the daughter of deaf parents and is now going deaf herself.

Their relationship quickly has consequences, especially when Billy brings her home to meet his family and a nasty argument—precipitated by his father’s incessant badgering of their guest--ensues over whether deaf people should isolate themselves in their own language.

Things come to a ferocious boil late in the play when Billy announces that his family members will have to learn signing, since that he is the only way he will communicate from now on.

Although imperfectly structured and paced, the play gets under your skin in a way that more polished dramas often do not. It possesses moments that are both raucously funny—some of the interactions between the troubled clan are priceless—and others that are deeply affecting.

Cromer is the Chicago-based director whose revelatory production of Thornton Wilder’s Our Town became a long-running hit at the Barrow Street Theatre, where this show is also playing. Once again he demonstrates an uncanny knack for how to use the space. His in-the-round staging featuring Scott Pask’s cleverly versatile set design provides such a depth of intimacy that we come to feel a part of the onstage family.

Although all of the performers are terrific, it’s Harvard’s emotionally wrenching portrayal that drives the evening. When Billy angrily turns on his family, it’s a truly heartbreaking moment. But even more moving is the silent gesture of reconciliation that follows—rarely has there been such a deeply felt depiction of familial love.

Barrow Street Theatre, 27 Barrow St. 212-868-4444. www.smarttix.com.