Review: Carrie

Mar 2nd

The original musical version of Carrie was a notorious flop upon its 1988 Broadway premiere--it closed after five performances at a loss of millions of dollars, nearly destroyed the reputation of the Royal Shakespeare Company, and was so ignominious in its failure that it lent its name to author Ken Mandelbaum’s now classic tome about Broadway musical disaster, Not Since Carrie.

Now it’s back, in a dramatically retooled and reconceived off-Broadway revival that attempts to strip away its camp excesses. But while the production generally succeeds in this aspiration, there’s an unfortunate side effect. It’s now simply dull.

Fans of Stephen King’s novel and Brian DePalma’s hit film adaptation are familiar with the story of Carrie White, the unfortunate high school wallflower with lethal telekinetic powers. Lawrence D. Cohen’s book for the musical is generally faithful to the source material, including such iconic moments as the blood-drenched prom and Carrie’s fateful final encounter with her religious fanatic mother. In what is perhaps a reflection on society’s current focus on the horrific effects of teen bullying, that aspect of the storyline is emphasized here to such a degree that Carrie sometimes feels like a supporting character. The attempt at psychological realism is understandable, but it results in an overall blandness that flattens the outlandish proceedings.

Director Stafford Arima takes a far more streamlined approach to the material than did Terry Hands in the big-budgeted original production, which featured lavish sets, bizarre production numbers, overblown special effects and buckets and buckets of fake blood. This scaled-down rendition relies mostly on lighting, projections and sound effects to convey the violent mayhem to generally impressive effect. The fact that not a drop of blood is used onstage is indicative of the overall restraint.

But the fact remains that the story, like most gothic tales, doesn’t particularly lend itself to musical treatment. And with the exception of “When There’s No One,” a haunting second act ballad sung by Carrie’s mother, the score by Michael Gore and Dean Pitchford (whose biggest claim to fame is the movie Fame) is generic, unmemorable pop-rock.

Molly Ransom is touching as Carrie, although she’s never quite as vulnerable or scary as the role demands. And as the obsessed Margaret, Marin Mazzie mainly seems miscast, failing to project the ferociousness that Piper Laurie and Betty Buckley respectively brought to the film and Broadway versions. She ultimately seems less scary than a typical Rick Santorum supporter.

This version of Carrie is certainly viable, and its name recognition should ensure that it gets produced in smaller theaters for a long time to come. But no amount of tinkering will ever make it a successful musical.

Lucille Lortel Theatre, 121 Christopher Street. 212-352-3101. www.mcctheater.org. Through April 22.

Review: Assistance

Feb 29th

Tyrannical bosses should be more careful about mistreating their employees. Their victims may very well develop into talented playwrights who will later skewer them in viciously funny fashion. Such is the case with Leslye Headland, whose Assistance is now receiving its New York premiere. Headland once worked as an assistant to movie producer Harvey Weinstein, but presumably any resemblance to her former situation in this play is purely coincidental. Yeah, right.

The playwright--who scored a hit with her off-Broadway comedy Bachelorette that she has now adapted into a film—has created a wickedly satirical look at life in the Tribeca office of “Daniel Weisinger,” where the assistants are routinely browbeaten, humiliated, insulted, used and abused. We never actually see or hear the boss, but their meek responses to his constant phone tirades paint the picture.

At the play’s beginning, new arrival Nora (Virginia Kull) is just settling into her first day, or more accurately first night, since she was kept waiting in the lobby for hours. Showing her the ropes is veteran employee Nick (Michael Esper), whose constant joking is merely a cover for his barely contained fear and anxiety.

Among the other victims, uh, employees are Vince (Lucas Near-Verbrugghe), who manages to score a promotion and move on to bigger things; Heather (Sue Jean Kim), who quickly burns out; Jenny (Amy Rosoff), whose British accent serves her well; and Justin (Bobby Steggert).

In the only scene not set in the office, the endlessly beleaguered Justin has a hilarious mental breakdown on the phone while attempting to “break up” with his shrink, who he clearly desperately needs.

The slight play is essentially a series of snarky one-liners as the assistants attempt to cope with their hellacious boss and his constant demands. But while not particularly deep or insightful, it’s so consistently funny and well acted by the talented young ensemble that the 80 minutes fairly fly by.

Esper and Kull are particularly good in their comic interactions, especially when their characters engage in some much needed sexual relief after a particularly intense upbraiding by their boss.

Director Trip Cullman has staged the piece in suitably frantic fashion, with the dialogue flowing with the speed of a vintage Howard Hawks comedy. And there’s a delicious coda that won’t be described here, but provides a wonderfully visual correlative to the emotional chaos that has preceded it.

Playwrights Horizons, 416 W. 42nd St. 212-279-4200. www.TicketCentral.com. Through March 11.

Review: Galileo

Feb 24th

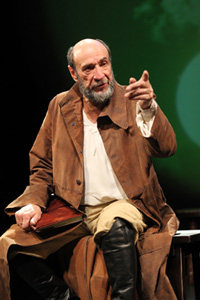

With partisan politics injecting itself into scientific debate with dismaying frequency these days, Bertolt Brecht’s Galileo has a disturbing modern resonance. While the Classic Stage Company’s revival of this rarely seen work doesn’t fully galvanize, it does offer the opportunity to watch Oscar winner F. Murray Abraham entertainingly sink his teeth into yet another juicy role.

Not that he over-emotes. In the title role of this play which bears any number of parallels with its playwright’s torturous political life, Abraham is all the more moving for his restraint. His matter-of-factness when depicting Galileo’s renunciation of his own theory about the earth orbiting the sun when he’s faced with torture is affectingly human.

Director Brian Kulick applies a number of typical Brechtian touches to his staging of the play, which is being presented in the translation by actor Charles Laughton that was first presented in 1947. But for all its ritualistic devices, songs and movement, the production is most affecting in its quieter, more subdued moments.

A first-rate supporting cast has been assembled, including Amanda Quaid as Virginia, the daughter whose burgeoning romance with a wealthy young man is threatened by her father’s controversial stands; Robert Dorfman as Cardinal Barberini, Galileo’s friend who is forced to betray him when he becomes pope; and Steven Skybell, Jon DeVries and Steven Rattazzi in multiple roles.

Adrianne Lobel’s set design, featuring floating orbs resembling planets, beautifully complements the play’s themes, with Justin Townsend’s lighting and Jan Hartley’s projections providing a suitably cosmic atmosphere.

Classic Stage Company, 136 E. 13th St. 212-352-3101. Through March 18.

Review: Early Plays

Feb 23rd

Although the stage seems bare for The Wooster Group’s production of Eugene O’Neill’s Early Plays, it actually contains an awful lot of baggage. The troupe is well known for their aggressively avant-garde approach to both new plays and the classics, adorning them with endless amounts of stylized movement and technological trickery. Meanwhile, guest director Richard Maxwell is typified by his minimalistic approach to both text and staging. The result of this unlikely collaboration is interesting if not wholly successful.

Of course, these early works by O’Neill—the production features three of his four one-act Glencairn plays set on or near a steamer and written in the first decade of the 20th century—would seem to defy modern staging. Deeply impressionistic and featuring dense and archaic dialect, they’re impenetrable at times. It’s no wonder that they’ve rarely been done even as the playwright has enjoyed a modern renaissance.

Maxwell’s approach here is to basically accentuate the text above all. And indeed it comes through with reasonable clarity, partly because a wise decision was made to have the actors avoid accents.

But the staging is pretty much non-existent. Performed on the same set that the company used for their production of The Emperor Jones, featuring just some cables and folding chairs (all the technical accoutrements, such as video screens, etc., are absent), the production has the feel of a staged reading…or more precisely, a table reading, and a first one at that. The actors vary wildly in their approaches, with some delivering fully formed, credible characterizations and other reciting their dialogue in a monotone that suggests they’ve never encountered it before.

That’s not to say that some effective atmospheric devices aren’t employed. The second play, Bound East for Cardiff, is performed in near total darkness, with only a spotlight at the rear of the stage to illuminate a couple of the actors. Musicians on the side of the stage provide a properly ominous background score. And the plays are bracketed by original, vintage-sounding songs composed by Maxwell that fit surprisingly well into the proceedings.

But despite some effective moments the production doesn’t manage to bring these works to any kind of vivid life. The task may perhaps be impossible, but it would be nice to see another attempt by a company with greater acting and directorial resources.

St. Ann’s Warehouse, 38 Water St. Brooklyn. 718-254-8779. Through March 11.

Review: Blood Knot

Feb 17th

It may be heretical to say, but seeing Athol Fugard’s landmark 1961 drama Blood Knot again, even in a superbly realized revival such as the one being presented by the Signature Theatre, is to be reminded how tedious it is. Such is the case, I’m afraid, with many of the playwright’s works, despite their historical and sociological importance. With one or two exceptions--Master Harold and the Boys being the most notable—Fugard’s dramas tend to be rambling and overly obvious in their themes. In most of them, you can be sure that the title will be dramatically uttered at one point, just to make sure we get the message.

This production--directed by the playwright and serving as the opener in a three-production season devoted to him—is the inaugural offering in the aptly named Alice Griffin Jewel Box Theatre in the company’s handsome new, Frank Gehry-designed theater complex dubbed The Pershing Square Signature Center.

The play concerns the relationship between two biracial South African brothers--one of whom is light enough to pass for white--who live together in a squalid shack on the outskirts of Port Elizabeth, South Africa. Zachariah (Colman Domingo) is a devil-may-care laborer at a whites-only park where his main job is to keep out his fellow blacks. The light-skinned, more ambitious Morris (Scott Shepherd), who has returned to his brother after a long absence, has dreams of saving up enough money to buy a farm for the two of them to run together.

Virtually nothing happens in the lengthy first act of this 2½ hour play, with the brothers engaging in lengthy verbal horseplay, much of it involving Morris’ efforts to procure a female pen pal and eventual love interest for his brother. Unfortunately, she turns out to be white.

Things turn slightly more dramatic in the second half, although the chief conflict revolves around a game of play-acting in which Morris gets all too carried away with his role as a white man and lets loose with a racial epithet that threatens to tear him and his brother apart. It foreshadows the later but similar angry prejudicial exchange that would figure so prominently, and to far greater effect, in Master Harold.

The venue’s intimacy certainly enhances the production’s impact, with the superb, fully lived-in performances by the two actors registering with a visceral intensity. Equally effective is Christopher H. Barreca’s rickety, ramshackle set, which is perched on a platform surrounded by detritus and literally comes apart in the play’s final moments, eerily mirroring the emotional desolation of the characters.

The Fugard season continues with a revival of his 1989 My Children! My Africa! followed by the New York premiere of The Train Driver.

Pershing Square Signature Center, 480 W. 42nd St. 212-244-7529. Through March 11.