Review: The Milk Train Doesn't Stop Here Anymore

Feb 4th

Tennessee Williams’ 1963 play The Milk Train Doesn’t Stop Here Anymore has defied success in all its previous incarnations. It flopped on Broadway not once but twice and the 1968 film adaptation—retitled Boom and starring Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton—fared no better. The current Off-Broadway revival being presented by the Roundabout Theatre Company, while essential viewing for Williams completists, is unlikely to salvage its reputation.

Tennessee Williams’ 1963 play The Milk Train Doesn’t Stop Here Anymore has defied success in all its previous incarnations. It flopped on Broadway not once but twice and the 1968 film adaptation—retitled Boom and starring Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton—fared no better. The current Off-Broadway revival being presented by the Roundabout Theatre Company, while essential viewing for Williams completists, is unlikely to salvage its reputation.

Here, the formidable Olympia Dukakis assumes the iconic role of Flora “Sissy” Goforth—an aging, widowed grande dame spending what are clearly her last days in her luxurious mountaintop villa on Italy’s Amalfi Coast. In between swilling alcohol and popping painkillers, she dictates her memoirs to her prim secretary, Blackie (Maggie Lacey).

Entering the picture is the handsome, gigolo-like Christopher (Darren Pettie), a former poet turned artist who designs mobiles. He has made a habit of attending to elderly women who have a propensity to soon kick the bucket, which has earned him the nickname of “Angel of Death.”

This hallucinatory meditation on mortality, written shortly after the death of the playwright’s longtime lover, is bizarre in the extreme. The central character, bearing elements of numerous other troubled female figures from the Williams canon, is the sort of grotesque creature for whom dressing up in full Kabuki regalia is a normal occurrence.

Adding to the camp factor is the character dubbed the “Witch of Capri,” Flora’s bitchy crony who has no compunctions about seducing everyone in sight, from her servants to the studly interloper. Although normally played by a woman, the role is entertainingly essayed here by Edward Hibbett, much in the same vein as Noel Coward in the film.

Although the play intermittently showcases Williams’ gift for blending poeticism with raucous humor, its disparate stylistic elements never fully coalesce. This rendition staged by Michael Wilson--cribbed from various drafts of the play and previously seen at Connecticut’s Hartford Stage—is certainly stylish but ultimately fails to bring cohesion to the muddled proceedings.

Dukakis manages at times to effectively convey Goforth’s grotesqueness. But her strained efforts are far too visible—the actress lacks the necessary diva-like presence to fully put the role over. Not helping matters is Pettie’s male ingénue. Although possessing serious sex appeal—his impressive physical attributes are fully revealed at one point—his blank mien makes the character no so much mysterious as simply bland.

Laura Pels Theatre, 111 W. 46th St. 212-719-1300. www.roundabouttheatre.org.

Reviews: The New York Idea / What the Public Wants

Feb 3rd

Two current revivals of vintage plays, one American and one British, demonstrate that not every forgotten drama from the past is necessarily worth excavating. Both the Mint Theater Company’s revival of Arnold Bennett’s 1909 What the Public Wants and the Atlantic Theater Company’s world premiere adaptation by David Auburn (Proof) of Langdon Mitchell’s 1906 The New York Idea mainly come across as theatrical relics.

Two current revivals of vintage plays, one American and one British, demonstrate that not every forgotten drama from the past is necessarily worth excavating. Both the Mint Theater Company’s revival of Arnold Bennett’s 1909 What the Public Wants and the Atlantic Theater Company’s world premiere adaptation by David Auburn (Proof) of Langdon Mitchell’s 1906 The New York Idea mainly come across as theatrical relics.

Both plays seem to have been unearthed for their supposed contemporary relevance. Mitchell’s comedy is a portrait of upper crust New York society dealing with new ideas about divorce and the role of women. Bennett’s is about a tabloid newspaper magnate who brings to mind a certain current media tycoon. Unfortunately, neither play works particularly well on dramatic terms.

I’m not familiar with the original version of Mitchell’s original, so it’s hard to know exactly how Auburn has transformed it, although no doubt extensive cutting was involved. It portrays the romantic roundelay among several characters: Cynthia (Jaime Ray Newman), a free-spirited young divorcee about to get remarried to the older Philip (Michael Countryman), a straight-laced judge; Philip’s ex-wife Vida (Francesca Faridany), who displays surprisingly modern attitudes about sex and marriage; and Cynthia’s former husband John (Jeremy Shamos), now in such desperate financial straits that he is forced to sell off all of his possessions, including her beloved race horse.

Observing from the sidelines are several peripheral characters, including the wealthy Sir Wilfrid (Rick Holmes), who attempts to woo Cynthia despite her upcoming nuptials.

While the play aims to be the sort of madcap romantic farce that would later be realized to perfection in such works as The Philadelphia Story, none of the situations or dialogue have the required comic zing. We care little about the characters, who seem little more than convenient mouthpieces for the provocative societal ideas being expressed. The climax of the play concerns the reconciliation of two of the former spouses, but by then we are so unengaged that it registers with little effect.

Under the sluggish direction of Mark Brokaw, the performers mainly struggle with their stock characters, although Newman, making her New York stage debut, brings a vivacity and charm to Cynthia that is largely missing from the rest of the evening.

The Mint, normally so savvy with their theatrical exhumations, is at a similar loss with this British comedy by Bennett, a wildly popular playwright in his day. Loosely based on the real-life figure of Lord Northcliffe, the founder of The Daily Mail, What the Public Wants originally found success both on the West End and in New York.

The Mint, normally so savvy with their theatrical exhumations, is at a similar loss with this British comedy by Bennett, a wildly popular playwright in his day. Loosely based on the real-life figure of Lord Northcliffe, the founder of The Daily Mail, What the Public Wants originally found success both on the West End and in New York.

It’s easy to see why the work seemed ripe for revival, dealing as it does with a publishing mogul who is desperate for both huge circulation and social prestige. He is the rich and successful Sir Charles Worgan (Rob Breckenridge), whose newspaper empire is based on feeding its readership sensationalism rather than the truth.

The return of his brother Francis (Marc Vietor) after nearly two decades spent abroad spurs Charles into self-reflection and a newfound desire to change his ways. Deciding that he needs to be married in order to become a respected member of society, he impulsively proposes to childhood friend Emily (Ellen Adair), now a struggling actress.

But when couple returns to their hometown for a family dinner, the resulting contentious family dynamics put the spotlight on their clashing values.

The playwright’s satirical observations, while certainly prescient for their day, seem all too familiar and redundant by now. The work plods along, suffering from a surfeit of minor characters, including a prickly theater critic apoplectic over the split infinitives popping up in his edited prose.

Although Matthew Arnold’s staging and the performances by the ensemble reflect the Mint’s usual solid level of professionalism, it’s hard to imagine that this antiquated work will be what the public wants.

The New York Idea

Lucille Lortel Theatre, 121 Christopher St. 212-279-4200. www.ticketcentral.com.

What the Public Wants

Mint Theater, 311 W. 43rd St. 212-315-0231, www.minttheater.org.

Review: The Misanthrope

Feb 2nd

It’s such a welcome pleasure to once again hear poet Richard Wilbur’s gorgeously elegant verse translation of The Misanthrope that one can almost, but not quite, overlook the general blandness of the Pearl Theatre Company’s revival. While Moliere’s 17th century comedy has lost none of its sharpness or power to amuse, this overly tame production hardly serves as a proper introduction to this too rarely performed classic.

It’s such a welcome pleasure to once again hear poet Richard Wilbur’s gorgeously elegant verse translation of The Misanthrope that one can almost, but not quite, overlook the general blandness of the Pearl Theatre Company’s revival. While Moliere’s 17th century comedy has lost none of its sharpness or power to amuse, this overly tame production hardly serves as a proper introduction to this too rarely performed classic.

Company regular Sean McNall stars as Alceste, the titular character who suffers fools badly and who can’t restrain himself from telling the truth to the fops and hypocrites surrounding him, consequences be damned. Declaring that he plans to “break with the whole human race,” he suddenly finds his principles tested when he falls in love with the beautiful but shallow Celimene (Janie Brookshire), the gossipy darling of the Parisian social scene who is fawned over by leagues of male admirers.

For some reason, director Joseph Hanreddy has updated the action to the 18th century, a curious choice since the playwright was pointedly satirizing the shallow conventions of the court of Louis XVI. And while it’s admirable that his restrained staging avoids the sort of overly broad comedy that too often afflicts productions of Moliere’s works, the proceedings are far too enervating.

Part of the problem is McNall’s performance. The actor is normally very reliable, but his too understated turn robs his character of the delicious outrageousness that normally provides the play of much of its humor. Equally underwhelming is Brookshire’s coquettish Celimene, although admittedly the actress looks smashing in Sam Fleming’s handsome costumes.

The supporting performances are mainly fine, with Kern McFadden particularly amusing as Oronte, the self-styled poet whose verses Alceste can’t help but nastily deride.

While the Pearl can’t be overly criticized for their inevitably modest production values, Harry Feiner’s set design is particularly underwhelming, looking more like a California patio than an elegant Parisian drawing room.

City Center Stage II, 131 W. 55th St. 212-581-1212. www.nycitycenter.org.

Review: American Idiot

Jan 31st

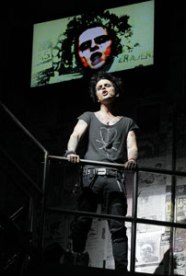

Imagine Frankie Valli stepping in on vocals for Jersey Boys. Or Ringo Starr manning the drum kit for the Beatles tribute Rain. Such is the electrifying effect of the presence of Green Day frontman Billie Joe Armstrong as the drug dealing St. Jimmy in American Idiot, the Broadway musical inspired by the best-selling pop-punk band’s Grammy winning 2004 concept album.

Armstrong has been involved with the show from the start, developing it and co-writing the book with director Michael Mayer. He also stepped into the show for a brief one-week run last September, which inevitably resulted in a massive hike in ticket sales.

Now, in an effort to boost box-office during the traditionally slow winter months, he’s in the midst of a sporadic 50 performance run. He played the role through January 30 and will return for a two-week engagement, running February 10-27.

His guest turn brings even more energy to a show that already suffers from no shortage of it. Despite his rock stardom and hugely charismatic stage presence, he melds seamlessly into an ensemble whose performances have only gotten stronger since the show opened last April.

The 95-minute musical incorporates all of the music from the titular album, as well as selections from the band’s 21st Century Breakdown and several other songs. The storyline concerns three disaffected suburban youth and the disparate paths on which they embark.

Johnny (John Gallagher, Jr.) heads to the big city, where he falls in love with Whatsername (Rebecca Naomi Jones) even while falling prey to drug addition at the hands of St. Jimmy. Tunny (Stark Sands) enlists in the army and is sent to Iraq, where he is gravely wounded. And Will (Michael Esper) finds himself stuck in suburbia, struggling to support his wife (Jeanna de Waal) and baby.

While the thinly drawn story and characters never become truly involving, Mayer’s propulsive staging smashingly overcomes the material’s flaws. Tom Kitt’s arrangements effectively theatricalize the hard-rocking and frequently melodic songs while diluting none of their original power. And Stephen Hoggett’s relentlessly energetic choreography is superbly performed by the youthful ensemble.

Far from being an example of stunt casting, Armstrong delivers a knockout turn, providing a devilishly antic spin to the character that is consistently mesmerizing. And, needless to say, he’s in utter command of the music. When he performs the hit song “Time of Your Life” at the encore, it’s sheer nirvana for the blissed-out Green Day fans.

Rock fans take note: Melissa Etheridge will be stepping into the role from Feb. 1-6. Is this the start of a series of guest stars ala the revival of Chicago?

St. James Theatre, 246 W. 44th St. 212-239-6200. www.telecharge.com.

Review: Green Eyes

Jan 27th

Theatrical experiences rarely come in more intimate forms than Green Eyes. This production of a long-lost Tennessee Williams play—how many of them are there, exactly?—is being performed in a room at midtown’s Hudson Hotel, with its fourteen audience members being within touching distance of the two barely clad performers.

Indeed, it’s not every show in which a comely actress asks a viewer’s help in removing her dress.

The immediacy adds greatly to the impact of Williams’ 1970 one-act, which depicts the emotionally and physically charged encounter between a pair of honeymooners in their hotel room in New Orleans’ French Quarter. Claude (Adam Couperthwaite) is a clearly traumatized soldier on temporary leave from serving in Vietnam. His sexually rapacious young wife (Erin Markey) is a sort of younger amalgam of various female characters from other Williams plays, alternately flirtatious and mocking.

Fueling the couple’s conflict is Claude’s discovery of a condom in the toilet, leading to his accusation of infidelity after she returned to the room alone the night before.

The two performers, clad mainly in their underwear (and Markey frequently in less) deliver no-holds barred turns, with their close proximity adding greatly to the evening’s intensity. Markey is particularly hypnotic, using a heavily Southern-accented drawl to accentuate her florid dialogue.

It’s a minor work, to be sure, gussied up here by Duncan Cutler’s ominous sound design which simultaneously evokes the passionate and occasionally violent nature of the characters’ interactions as well as Claude’s recent military experiences. Another reminder of the latter is the appearance of a breakfast toting bellhop wearing army fatigues, his face painted camouflage style.

While one wouldn’t particularly want to be staying in one of the hotel’s adjacent rooms—one can imagine that there are more than a few complaining calls to the front desk, considering the volume of the shouted dialogue—this environmental staging adds greatly to the theatrical impact of this brief but fascinating footnote to the playwright’s career.

Hudson Hotel, 356 W. 58th St. 212-352-3101. www.ovationstix.com.