Review: Elling

Nov 22nd

It was an Oscar nominated foreign-language film and a hit on the West End in London, but Elling proves well nigh insufferable in its Broadway incarnation. Playwright Simon Bent’s adaptation of the Norwegian novels by Ingvar Ambjornsen and the subsequent acclaimed movie proves itself to be a throwback to such dated 1960’s era films as “King of Hearts” in its depiction of mental illness as a compendium of comic quirks.

It was an Oscar nominated foreign-language film and a hit on the West End in London, but Elling proves well nigh insufferable in its Broadway incarnation. Playwright Simon Bent’s adaptation of the Norwegian novels by Ingvar Ambjornsen and the subsequent acclaimed movie proves itself to be a throwback to such dated 1960’s era films as “King of Hearts” in its depiction of mental illness as a compendium of comic quirks.

Denis O’Hare and Brendan Fraser play the central roles of Elling and Kjell Bjarne, two residents of a mental asylum who are released and set up in a pristine Oslo apartment to make their own way in the world. Under the supervision of social worker Frank (Jeremy Shamos), they learn to experience life and love while developing a strong bond in the process.

Obsessive/compulsive Elling is the far more intellectual of the duo; he describes his institutionalization as having accepted an offer from the government to supply a place for “people who are in a hectic phase in their lives.” The overgrown man/child Kjell is a forty-year-old virgin who obsesses about food and sex and who has a recurring problem with his uncontrollable erections.

The play depicts their burgeoning relationships with each other and with such figures who enter their lives as Reidun (Jennifer Coolidge), a pregnant upstairs neighbor with whom Kjell falls hopelessly in love, and Alfons (Richard Easton), an elderly poet who helps Elling channel his artistic impulses.

The play’s humor derives from the main characters’ respective peculiarities. Giving his roommate a gift of a miniature house made out of matchsticks, Kjell proclaims, “If you don’t like it I’ll kill myself.” He nearly passes out from pleasure while eating his first slice of home-delivery pizza, and becomes obsessed with phone sex lines. Elling transforms himself into the “Sauerkraut Poet,” inserting his verse into packets of sauerkraut at random supermarkets.

Under the uninspired direction of Doug Hughes, it’s all too cutesy by far, and despite the especially game performances by O’Hare and Fraser (the latter looking far different from his buff days as “George of the Jungle”) the evening meanders to the point of inconsequentiality.

Coolidge is, as usual, hysterically funny in her multiple roles, especially in her brief turn as a pretentious poet who delivers a sample of her works that were written “while sick with malaria in Cambodia.” Easton offers study support as Elling’s mentor and Shamos is winning as the beleaguered social worker. But their efforts are ultimately defeated by the evening’s witless triviality.

Ethel Barrymore Theatre, 243 W. 47th St. 212-239-6200. www.Telecharge.com.

Review: A Free Man of Color

Nov 19th

There’s so much energy, intellectual ambition and gorgeous stagecraft on display in A Free Man of Color that it’s disheartening to report that it barely works at all. John Guare’s comic, historical epic dealing largely with the Louisiana Purchase is so willfully abstruse, so eager to show off, that audience reaction seems to have been merely an afterthought.

There’s so much energy, intellectual ambition and gorgeous stagecraft on display in A Free Man of Color that it’s disheartening to report that it barely works at all. John Guare’s comic, historical epic dealing largely with the Louisiana Purchase is so willfully abstruse, so eager to show off, that audience reaction seems to have been merely an afterthought.

Set between 1801-1806 in locations including New Orleans, France, Spain and others, the work is presented in the grand style of Restoration comedy, complete with the occasional rhyming couplets.

The titular character is Jacques Cornet (Jeffrey Wright, making a too long delayed return to the New York stage), a roué who glories in cutting his romantic swath among the eager women of New Orleans. The mulatto son of a wealthy white man and a black slave, he himself owns several slaves, including Murmur (Mos, apparently no longer Def, here reuniting with Wright for the first time since Topdog/Underdog).

But the foppish, florid Cornet is but one of some forty characters in this sprawling tale, which also features such real-life historical figures as Thomas Jefferson (John McMartin), explorer Meriwether Lewis (Paul Dano), James Monroe (Arnie Burton), Robert Livingston (Veanne Cox) and Napoleon (Triney Sandoval).

The piece varies wildly in tone, with the heavily stylized first act particularly alienating. The playwright frequently indulges in broad strokes of fantastical humor, such as his depiction of a grotesque phallus-wearing Napoleon who delivers a lengthy rant about everything British, including such modern icons as Julie Andrews and James Bond.

Although clearly attempting to examine such serious thematic issues as race relations and class differences in early 19th century America, Guare squanders the inherent potential of his fascinating subject matter and milieu with his kitchen sink approach to the material.

The labored work settles down somewhat in its second half, when it adopts a far more somber and direct tone. But by that time, the ceaseless and confusing procession of characters and subplots has drained most of our energy and attention.

Director George C. Wolfe, no stranger to sprawling epics (Angels in America), is unable to bring any real cohesion to the proceedings. He does, however, invest them with an undeniably striking theatricality, aided mightily by David Rockwell’s extravagant, versatile sets and Ann Hould-Ward’s gorgeous period costumes.

Wright is certainly arresting as Cornet, although his posturing eventually becomes slightly wearisome. Faring best are the performers who are allowed to stay relatively grounded in their characterizations, such as Mos’ resentful slave, McMartin’s conflicted Jefferson and Dano’s resolute Lewis.

Vivian Beaumont Theater, 150 W. 65th St. 212-239-6200. www.lct.org.

Review: The Merchant of Venice

Nov 15th

Al Pacino famously spends years obsessing on the Shakespearean roles he takes on, but the results definitely pay off. Such is the case with his Shylock in the production of the Bard’s still controversial The Merchant of Venice that has transferred to Broadway—with some cast changes---after a brief run summer run in Central Park. While his performance in the 2004 film often came across as mannered, his stage rendition is undeniably mesmerizing. His starring turn anchors director Daniel Sullivan’s thoughtful revival which is attracting sell-out crowds.

Al Pacino famously spends years obsessing on the Shakespearean roles he takes on, but the results definitely pay off. Such is the case with his Shylock in the production of the Bard’s still controversial The Merchant of Venice that has transferred to Broadway—with some cast changes---after a brief run summer run in Central Park. While his performance in the 2004 film often came across as mannered, his stage rendition is undeniably mesmerizing. His starring turn anchors director Daniel Sullivan’s thoughtful revival which is attracting sell-out crowds.

Set in the Edwardian era, the production doesn’t sacrifice the comedic aspects of the play--the scenes involving Portia’s (Lily Rabe) ill-fated suitors are consistently hilarious--but its atmosphere is mainly harrowing. Antonio, the Christian nobleman, is powerfully portrayed by Byron Jennings as a condescending aristocrat whose barely disguised contempt fuels Shylock’s lust for revenge. Later, when he is about to be forced to give up his pound of flesh, he is chillingly strapped into an antique medical examination chair.

The director’s biggest innovation is the addition of a powerful silent scene in which we see Shylock submitting to a forced baptism. It not only vividly conveys the character’s humiliation, but also his inner strength as he afterwards immediately resumes wearing the yarmulke that has been stripped from his head.

Often speaking in a soft, sing-song voice, Pacino at first playfully emphasizes the character’s wily intelligence and humor, as well as his pained awareness of the marginal role in society to which he has been consigned. But after Shylock’s daughter Jessica (Heather Lind) runs off with her Christian boyfriend Lorenzo (Seth Numrich), he accentuates the bitterness that feeds the character’s steely resolve.

Lily Rabe brings both beauty and intelligence to her superb performance as Portia, and is uncommonly convincing in the pivotal scene in which her character assumes the identity of the male judge deciding Antonio’s fate.

The supporting roles are also finely handled, with especially solid turns by David Harbour as Bassanio, Marsha Stephanie Blake as the gentlewoman Nerissa and Jesse L. Martin as Gratiano. Christopher Fitzgerald expertly mines the expected laughs as Shylock’s servant, Launcelot Gobbo.

The production elements are first-rate, with Mark Wendland’s striking set design largely consisting of an abstract series of metallic circles that cannily echoes the wedding bands that figure so prominently in the plotline.

Broadhurst Theatre, 235 W. 44th St. 212-293-6200. www.telecharge.com. Through Jan. 9.

Review: Elf

Nov 15th

It makes sense that, like the Disney and Dreamworks studios, Warner Bros. would want to mine its cinematic properties for Broadway musical treatment. Less understandable is why, for their attempt at a Christmas perennial with an adaptation of the hit Will Ferrell comedy Elf, they would turn to the same composers responsible for their previous venture, the ill-fated The Wedding Singer.

It makes sense that, like the Disney and Dreamworks studios, Warner Bros. would want to mine its cinematic properties for Broadway musical treatment. Less understandable is why, for their attempt at a Christmas perennial with an adaptation of the hit Will Ferrell comedy Elf, they would turn to the same composers responsible for their previous venture, the ill-fated The Wedding Singer.

Matthew Sklar and Chad Beguelin’s score for Elf--which has arrived on Broadway for a limited holiday engagement ala How the Grinch Stole Christmas and Irving Berlin’s White Christmas--is similarly unimpressive, and the show, despite boasting plenty of talent both on and off stage, is a theatrical lump of coal.

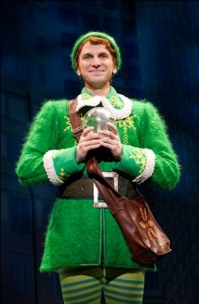

Hewing closely to the 2003 film, it tells the story of Buddy (Sebastian Arcelus), a suspiciously tall elf who works for Santa (George Wendt) at the North Pole. When Buddy finds out that he is actually human, he sets off for New York City in search of his identity.

There, he finds his real father, children’s book publishing exec Walter Hobbs (Mark Jacoby), who now has a second wife (Beth Leavel) and young son (Matthew Gumley). While attempting to ingratiate himself to his curmudgeonly dad, the childlike Buddy strikes up a burgeoning romance with cynical Macy’s employee Jovie (Amy Spanger) and attempts to restore Christmas spirit to everyone concerned.

“I’m an orphan, just like Annie,” announces Buddy at one point, but this show is no Annie, despite the fact that it shares the same writer, Thomas Meehan, here collaborating with Bob Martin (The Drowsy Chaperone). Their charmless book is filled with plenty of cheap gags addressed to the adults (“Don’t go all Charlie Sheen on me” is a typical example) and topical updates (Santa uses an iPad to keep track of things) when it’s not being hopelessly corny. Clearly aimed at the annual tourist holiday influx, it features scenes set at such iconic NYC locations as the Rockefeller Center skating rink, the Empire State Building, Macy’s, Chinatown and even the now closed Tavern on the Green.

Director/choreographer Casey Nicholaw (The Drowsy Chaperone, Monty Python’s Spamalot) keeps things moving at a sprightly enough pace, with the occasional number, such as the elaborate “Sparklejollywinklejingley,” displaying real inventiveness.

But his efforts are defeated by the generic score featuring numerous songs struggling mightily to become Christmas standards but not hitting the mark.

Arcelus, faced with the undeniably difficult task of filling Ferrell’s shoes, is largely unappealing in the lead role, seeming so young and boyish that all of the comedic potential of his man/child character is essentially squandered. The talented supporting performers are given too little to do to distinguish themselves, while Wendt’s endearing Santa is seen only in brief prologue/epilogue appearances in which he’s even forced to deliver the obligatory cell phone/candy wrapper warning.

Al Hirschfeld Theatre, 302 W. 45th St. 212-239-6200. www.Telecharge.com. Through Jan. 2.

Review: The Pee-Wee Herman Show

Nov 12th

Stephen Sondheim Theatre, NYC

His fans may have aged, but somehow Pee-wee Herman, aka Paul Reubens, has somehow managed to avoid the ravages of time. Appearing for the first time on Broadway in a revamped version of the live show that first garnered him fame nearly three decades ago, the actor’s singular, iconic creation proves ready to conquer yet another world.

His fans may have aged, but somehow Pee-wee Herman, aka Paul Reubens, has somehow managed to avoid the ravages of time. Appearing for the first time on Broadway in a revamped version of the live show that first garnered him fame nearly three decades ago, the actor’s singular, iconic creation proves ready to conquer yet another world.

It’s amazing that, in his late fifties, Reubens would still be capable of credibly playing the oversized man/child with the too tight clothes. But the still lanky actor has retained the physicality and, more importantly, the manic energy that endeared the character to children of all ages.

It immediately becomes clear--judging by the rapturous ovations greeting the appearances of the iconic playhouse set and every familiar character—that neither the passage of time nor a certain scandal have done little to diminish their ardor for the classic “Pee-wee’s Playhouse” television series.

Fans will be relieved to know that all of its elements have been dutifully reprised, including such characters as Miss Yvonne, Cowboy Curtis, Pterri the Pterodactyl, Jambie the Genie and perhaps its most beloved figure, Chairry. Besides Reubens, three of the original performers are on hand to reprise their roles: John Moody (Mailman Mike), John Jaragon (Jambi) and Lynne Marie Stewart (Miss Yvonne). For this show, a new character has also been introduced: Sergio the Handyman (Jesse Garcia), with whom Pee-wee engages in comically fractured Spanish dialogue.

Truth be told, the script, written by Reubens and Paul Steinkellner with additional material by Paragon, is somewhat lacking in true wit. Considering its perfunctory storyline of Pee-wee yearning to fly and the series of lame, adult-directed double entendres, non-fans are likely to be left wondering what all the fuss is about.

The gags--ranging from the classic (Pee-wee’s mantra of “I know you are but what am I?”) to the contemporary (bits about social networking, abstinence rings and such celebs as David Beckham and The Situation)—are hit and miss.

But the show is bursting with visual invention, from David Korin’s faithful replication of the original, garishly colored set to the eye-popping costumes to Basil Twist’s superb puppetry. And there are moments, such as Reubens’ lengthy mimed struggle with a balloon and Pee-wee’s climactic joyful launch into flight, that are undeniably magical.

Whatever quibbles there are to be found, “The Pee-wee Herman Show” represents a triumphant comeback for the indefatigable Reubens and his signature creation, who with any luck will once again grace the big screen.

Stephen Sondheim Theatre, 124 W. 43rd St. 212-239-6200. Telecharge.com. Through Jan. 2