Review: Not by Bread Alone

Jan 24th

If the performers onstage at NYU’s Skirball Center seem to be in their own world, that’s because they really are. They’re the members of Israel’s Nalaga’at Theater, and they’re all, to varying degrees, both deaf and blind. But that doesn’t stop them from fully expressing themselves in their beautifully heartfelt production, Not by Bread Alone.

Conceived and directed by Adina Tal, the evening is a collection of vignettes and skits, some poignant, some farcical, in which the cast members convey what it’s like to live in their sensory-deprived world. Their words are communicated via supertitles and translators; they’re gently guided around the stage by a crew of black-clad handlers; and they receive their cues via the pounding of drums from which they sense the vibrations.

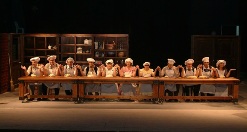

As we enter the theater the eleven performers are already visible, seated at a long table and busily kneading dough which is eventually placed in several onstage ovens. As the show proceeds, the pleasant aroma of baking bread permeates the auditorium, but thankfully it’s no tease. At the conclusion the audience is invited to literally break bread with the performers onstage, in an affirmation of the communal bond that’s been formed.

The piece is most effective at its simplest. An older woman touchingly describes the despair she felt upon the realization that she’ll never see the face of her grandson. Another relates how important it is for him to shake the hand of a person he’s meeting, just as proof that they really exist. Several relate the history of their condition, and whether or not they have any memories of sights or sounds.

The attempts at clowning and visual comedy are less successful, with vaudeville-style sketches depicting such events as a visit to a hairdresser, an Italian vacation and a wedding having a forced, strained quality that’s in marked contrast to the naked honesty evidenced by the performers while simply telling their own stories.

To fully immerse yourself in the experience, you’ll want to shell out for the admittedly pricey ($200) show and dinner package. The company has imported two signature elements from its home theater in Tel Aviv: the Café Kapish, featuring deaf servers, in which orders are taken only via sign language; and the BlackOut restaurant. In the latter, you’re served a three-course meal in complete darkness by blind waiters who use bells to communicate their movements. The dishes created by famed NYC restaurateur Danny Meyer (Union Square Café, Gramercy Tavern) feature a wide array of tastes and textures which must be discerned without the usual visual accompaniment. For an hour at least, you’ll at least have a partial idea of the world these performers inhabit every day of their lives.

Skirball Center for the Performing Arts, 566 LaGuardia Place. 212-352-3101. www.nyuskirball.org. Through Feb. 3.

Review: Cat on a Hot Tin Roof

Jan 18th

There are plenty of fireworks in the new Broadway revival of Tennessee Williams’ Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, but sadly they’re all offstage. For this production marking Scarlett Johansson’s return to Broadway after winning a Tony Award for A View From the Bridge, director Rob Ashford has pulled out all the stops. Music, sound and lighting effects are employed to extravagant effect, but they do little to cover up the listlessness at the show’s core.

Clearly designed as a star vehicle for the white-hot Johansson—this is the third Broadway production of the play in less than a decade—this is more of a cat on a tepid tin roof. The actress, so impressive a few years ago in Arthur Miller’s play, seems to be struggling here. Her voice reduced to a husky rasp, she races through her lines in the first act as if desperate to get the whole thing over with. Although she’s more effective in the climactic scene, her Maggie never fully projects the necessary sultriness and wiliness as she desperately attempts to seduce her disaffected husband. Even more strangely, the staging somehow manages to strip her of her natural sexiness.

Benjamin Walker (Bloody, Bloody Andrew Jackson) fares even less well as the neutered, alcoholic Brick, bereft since the death of his best friend Skipper. (The production originally featured an actor playing the character as a ghost, a device that has wisely been jettisoned.) The tall, lanky Walker certainly has the physical attributes for the part, amply revealed since he spends much of the proceedings clad only in a towel. But he overdoes the character’s morose depression to such a degree that he’s also boring and charisma-free. The staging also does him no favors, as he’s constantly limping around the set with his crutches and frequently being thrown about as if he was a rag doll and not a strapping former athlete.

Scottish actor Ciaran Hinds is a formidable and imposing Big Daddy, and his lengthy second act confrontation with Walker’s Brick is the most dramatically arresting part of the evening. But Hinds also emphasizes the character’s fearsome bluster to such a degree that he fails to convey the humor and larger-than-life qualities that such predecessors as Burl Ives and James Earl Jones brought to the part. The ever-reliable Debra Monk is a suitably pathetic Big Mama, while Emily Bergl makes the scheming, ridiculously fertile Mae more appealing than she has a right to be.

Director Ashford tries to ratchet up the intensity by constantly moving the actors around at a feverish clip and having them scream at the top of their lungs, but the results are mostly enervating. This is a shockingly unmoving Cat, one that keeps the audience removed from the intense machinations taking place. Christopher Oram’s set design, looking more like a grand ballroom than a bedroom in a Southern mansion, is similarly both over-the-top and ineffectual.

Thanks to Johansson’s star power, the revival is bound to do well at the box-office. But this misconceived, undercooked Cat mainly demonstrates that it may be time to give this oft-performed warhorse of a classic a well-deserved rest.

Richard Rodgers Theatre, 226 W. 46th St. 877-250-2929, www.catonahottinroofbroadway.com. Through March 30.

Review: The Other Place

Jan 11th

The central character in Sharr White’s drama The Other Place is suffering the disorientating effects of a condition she’s self-diagnosed as brain cancer. Her helpless confusion is likely to be shared by the audience, as the play seems intent on providing shifting perspectives that keep us constantly guessing as to what’s actually going on. The results are undeniably compelling but also frustratingly gimmicky, as if the playwright was more interested in pulling the rug out from under us than fully involving us in her character’s plight.

Laurie Metcalf, repeating her role from last year’s well-received off-Broadway production, delivers a galvanizing performance as Juliana, a former scientist who now makes her living as a pitchperson for a pharmaceutical company. Delivering a lecture at a conference in the Virgin Islands, she finds herself suddenly unable to form coherent thoughts, endlessly distracted by a young attendee clad only in a yellow bikini who she repeatedly harangues.

In subsequent confrontations with her oncologist husband (a sympathetic Daniel Stern) who she’s in the process of divorcing and a female doctor (Zoe Perry) who he’s enlisted to examine her, Juliana proves alternately vulnerable and abrasive. The former quality is markedly evident in her poignant attempt to reconcile with her estranged daughter (Perry, again) who left home years earlier to run off with an older man (John Schiappa).

Or did she? That’s one of the many tantalizing questions presented by the fractured narrative that correlates with Juliana’s confused mental state. To reveal more of the play’s secrets would be unfair, but it should be pointed out that it’s at its most effective in the climactic scene in which Juliana fully comes to grips with her circumstances via an encounter with a young woman (Perry, in her third role) who she takes to be her daughter. Devoid of narrative machination, it packs an emotional punch that much of the coldly clinical play otherwise lacks.

Still, the play is well worth seeing, thanks to both to Metcalfe’s ferociously funny, intense performance—sure to be remembered at Tony Award time--and the effectively visceral staging by director Joe Mantello. The production elements convey the main character’s mental confusion in vivid fashion, from Eugene Lee and Edward Pierce’s set composed of hundreds of empty frames to Fitz Patton’s hallucinatory sound design to William Cusick’s haunting projections.

Samuel J. Friedman Theatre, 261 W. 47th St. 212-239-6200. www.Telecharge.com. Through Feb. 24.

Review: Glengarry Glen Ross

Dec 9th

Ah, the benefits of diminished expectations. Since it began previews in October, the Broadway revival of David Mamet’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Glengarry Glen Ross has been the target of negative buzz--primarily over Al Pacino’s unfocused performance--which only got louder when the production delayed its opening for a month, supposedly because of Hurricane Sandy. Well, the show has finally been deemed ready to be seen by critics, and it’s a pleasure to report that it’s fully up to snuff.

That the production is housed in a theater just a few yards away from the soon-to-be shuttered The Anarchist, Mamet’s most recent, critically reviled effort, ironically serves as a reminder that this superb dramatist seems to have lost his way in recent years.

The 1983 play, last seen on Broadway as recently as seven years ago, holds up marvelously well in its depiction of American capitalism as its most cutthroat. Set in a sleazy Chicago real estate office, it depicts the savage machinations among a motley group of rapacious salesman desperately competing with each other to get to the top of the sales tote board and receive the Cadillac that goes with it. Or at least, not lose their jobs.

Chief among them is the fast-talking Ricky Roma (a superb, perfectly cast Bobby Cannavale), who in an early scene is seen delivering a slick sales pitch in a Chinese restaurant to a hapless potential customer (Jeremy Shamos), like a jungle predator circling its prey.

The veteran member of the tribe is the aging Shelly “The Machine” Levine (Pacino), who desperately tries to procure invaluable leads from the stand-offish office manager (David Harbour) by blatantly offering him kickbacks.

The plot is set in motion when salesman Dave Moss (John C. McGinley) attempts to persuade his whiny colleague George (Richard Schiff) to break into the office and steal the all-important leads, which they will then sell to the competition. Act Two concerns the aftermath of the robbery, with an officious detective (Murphy Guyer) hauling them into an office one-by-one for interrogation.

Filled with Mamet’s trademark hilariously pungent and profane dialogue, the play is a marvel of concision and character illumination, especially in its handling of the alternately pathetic and boasting Levine. As played with hangdog pathos and expert comic timing by Pacino, the character is a haunting reminder of the fragility of success.

Director Daniel Sullivan has assembled an expert ensemble for his crackling production, with every actor embodying his role with a fully lived-in authenticity. Eugene Lee’s sets and Jess Goldstein’s costumes are equally spot-on for this revival which has been unfairly maligned as a mere star vehicle for Pacino. Not that there’s anything wrong with that, either.

Gerald Schoenfeld Theatre, 236 W. 45th St. 212-239-6200. www.Telecharge.com. Through Jan. 20.

Review: Golden Boy

Dec 7th

Clifford Odets’ rarely seen 1937 drama Golden Boy is receiving a loving revival courtesy of the Lincoln Center Theater, which previously mounted his classic Awake and Sing! to great acclaim. Given historical resonance by its being performed at the Belasco, the very theater in which it was presented by the legendary Group Theatre 75 years ago, this stirringly staged and beautifully acted production succeeds in bringing this melodramatic but still powerful work to dramatic life.

Director Bartlett Sher has assembled a superb nineteen-member ensemble for the show, which tells the story of Joe Bonaparte (Seth Numrich), the son of a widowed Italian immigrant (Tony Shalhoub) who dreams of his son fulfilling his talents as a violinist. Instead, Joe decides to go for the easy money as a prize fighter, despite the risks it poses to his hands. After brashly barging into the office of low-level boxing promoter Tom Moody (Danny Mastrogiorgio), Joe begins his ascent to the top while falling in love with Moody’s beautiful young mistress Lorna (Yvonne Strahovski, of TV’s Dexter), who soon returns his affections.

As his father helplessly watches in dismay from the sidelines, Joe quickly succumbs to his vision of the American dream, which in this case includes the complicity of a vicious, dandyish gangster (the compelling Anthony Crivello) who takes an unhealthy interest in his latest acquisition. He eventually indeed rises to the top, but at a tragic personal cost.

Odets’ drama, inspired by his own self-disgust at selling out to Hollywood, has no shortage of hoary elements. The characters are often stereotypical—the father’s Jewish best friend, the philosophy spouting Mr. Carp (Jonathan Hadary), being a prime example—and the play is not exactly subtle in its hammering home of its themes and allegories. But it remains compelling nonetheless, thanks to its frequently funny, pungent dialogue and its sheer conviction.

Director Sher displays a great affinity for the dated material, giving the production a vintage feel in its performances and design that honors the past while not devolving into a museum piece. The look of the show is gorgeous, from Michael Yeargan’s striking sets seemingly inspired by Edward Hopper’s paintings to Donald Holder’s expressionistic lighting to Catherine Zuber’s period-perfect, character revealing costumes.

The large cast composed of many theater veterans strikes all the right notes. Although Numrich is never fully convincing as a literally killer fighter, he delivers a sensitive, anguished portrayal that is always riveting. The gorgeous Strahovski, in the role originally played by Frances Farmer, perfectly conveys Lorna’s complex mixture of toughness and vulnerability; Shalhoub is deeply moving as the father who loves his son no matter what; and Danny Burstein beautifully underplays as Joe’s caring trainer. But there isn’t a weak link the cast, which also includes such reliable pros as Ned Eisenberg, Daniel Jenkins and Dagmara Domincyzyk.

Belasco Theatre, 111 W. 44th St. 212-239-6200. www.telecharge.com. Through Jan. 20.