Review: The Submission

Playwright Jeff Talbott clearly knows the territory that he explores in The Submission. Having had his previous efforts presented at numerous theater festivals, he’s well in a position to lend verisimilitude to this darkly satirical portrait of a gay male playwright who invents a fictitious African-American female identity for himself in order to get his new work accepted by the Humana Festival.

Unfortunately, despite the sort of in-the-know references that regular theatergoers will appreciate—such as one character commenting on the commercial viability of a four character, one-set play, which this one happens to be—The Submission doesn’t exactly provide any revelations when it comes to the deeper aspect of its subject. Much like David Mamet’s Race, the main point being made here is that all of us, even liberals and minorities are, gasp, just a little bit prejudiced.

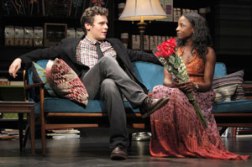

It’s not that the taut comedy/drama isn’t sharply written. Talbott has provided pungently amusing dialogue for his characters, who include struggling playwright Danny (Jonathan Groff), whose latest effort concerns a single black mother and her son struggling to survive in the projects; his lover Pete (Eddie Kaye Thomas), always ready with a wisecrack; Emilie (Rutina Wesley), the young black actress who Danny asks to assume his made-up identity of “Shaleeha G’ntamobi”; and Trevor, Danny’s friend who strikes up a relationship with Emilie.

But the well-drawn characters aren’t enough compensation for the more contrived and unbelievable aspects of the story, such as Danny’s repeated assertion that he and Emilie will become rich if their plan succeeds. Really? That will certainly come as news to most members of the playwriting profession.

The play’s certainly been given an impressively slick production courtesy of director Walter Bobbie. The performances, too, can’t be faulted, with Wesley--best known for her regular role on HBO’s True Blood--particularly compelling. But while admirable in its willingness to take on the sacred cow that is the presumed liberalism of the American theater scene, the play seems more designed to posit its intellectual arguments than provide any emotional resonance.

| Print article | This entry was posted by Frank on 09/30/11 at 06:52:04 am . Follow any responses to this post through RSS 2.0. |