Review: The Mountaintop

Oct 14th

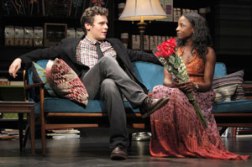

One of history’s greatest ironies is that Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his soaring “I’ve have been to the mountaintop” speech on the very night before his death. Now, emerging playwright Katori Hall has imagined the events of that final evening at the Lorraine Motel in her work The Mountaintop. This Olivier-Award winning play, being presented on Broadway in a production starring Samuel L. Jackson and Angela Bassett, is a theatrical tour de force.

As magnetically played by Jackson, King is here presented as a compellingly human figure: exhausted, battling a cold; deeply upset about the Vietnam War and concerned about his safety. He also apparently has “stinky feet,” and desperately needs cigarettes and coffee.

Supplying the latter items is Camae (Bassett), the attractive chambermaid who delivers them to his room during a torrential rainstorm. Sassy, provocative and a bit flirtatious, she stirs more than just friendly interest from King.

At first the two playfully banter over such lighthearted matters as whether King should keep his moustache and the proper poses to strike while smoking—meanwhile, the periodic bursts of thunder have him flinching as if they were gunshots. But the encounter soon takes a more surreal tone, as Camae, who describes God as a black woman, turns out to have a very particular agenda.

While the playwright is not fully successful in elevating her work into a deeper commentary on the progress of racial relations in America, The Mountaintop is so entertaining and insightful along the way that it hardly matters. And whatever deficiencies there are in the writing are compensated for by the masterful staging of Kenny Leon, who--aided by David Gallo’s amazing set and projections-- delivers a stunningly climactic coup de theatre.

Although he bears little physical resemblance to King and doesn’t truly alter his distinctive vocal mannerisms, Jackson, with the aid of subtle make-up and hair styling, is a reasonable facsimile. More to the point, he’s hilariously funny—never more so than during an aggrieved phone conversation with God—as well as deeply moving when conveying the civil rights leader’s fears and vulnerabilities.

Bassett is even better, stealing the show with her wildly raucous and earthy portrayal that fully mines her character’s humorous and otherworldly qualities. And her delivery of Hall’s superbly written poetic monologue encapsulating modern black history is blisteringly visceral. It’s very early in the season, but it’s hard to imagine a performance that could beat this one come awards time.

Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre, 242 W. 45th St. 212-239-6200. www.Telecharge.com.

Review: The Lyons

Oct 12th

Contemporary playwrights seem forever bent on proving Tolstoy’s line that “all families are unhappy in their own way.” The latest example is Nicky Silvers, who has mined such territory to fruitful comic effect in plays like Raised in Captivity, The Food Chain and others. Unfortunately, The Lyons, his latest effort, feels all too redolent of the sort of untapped anger and shame that would have been better explored in therapy.

The characters in this dark comedy directed by Mark Brokaw are all troubled or repellant. Ben (Dick Latessa), the patriarch of the Lyons family, is dying of cancer, but that doesn’t stop him from spewing obscene tirades at everyone around him. His long-suffering wife Rita (Linda Lavin) mainly sits by his bed flipping the pages of a magazine in-between providing acidly sarcastic comments. Daughter Lisa (Kate Jennings) is a divorced alcoholic, and gay son Curtis (Michael Esper) clearly has psychological issues.

The play’s first act, set in Ben’s hospital room, is cohesive enough, with the family members basically insulting each other with impunity. The playwright hasn’t lost his ability to craft sharp one-liners, which are delivered by old pros Latessa and Lavin with comic perfection. But the humor is forced, with a heavy reliance on would-be shocking profanity to garner cheap laughs.

The play goes completely off the rails in the second act, especially in a lengthy scene depicting an encounter between Curtis and a hunky real estate broker (Gregory Wooddell) that takes a shocking and violent turn. Curtis then winds up in the hospital, being attended to by the same nurse (Brenda Pressley, making the most of her small role) that handled his late father.

To many theater insiders’ surprise, Lavin took this role rather than transfer to Broadway in the acclaimed productions of Other Desert Cities or Follies. It’s easy to see why the actress was attracted to her role here—it’s a deliciously colorful one, and she basically runs away with the evening. But compared to those works, The Lyons is a trivial, shallow enterprise that only exploits her considerable talents.

Vineyard Theatre, 108 E. 15th St. 212-353-0303. www.vineyardtheatre.org.

Review: Man and Boy

Oct 10th

Terence Rattigan’s Man and Boy was written in the 1960s and is set in the 1930s, but it would unfortunately resonate in any decade. This portrait of a desperate business tycoon was inspired by an obscure, real-life figure. But modern audiences may be forgiven for thinking of a certain recently notorious Ponzi schemer while watching it.

The Roundabout Theatre Company is presenting a cannily timed revival of this largely forgotten work—a flop in its original 1963 London and Broadway productions—that offers a juicy star turn for Frank Langella.

The 73-year-old delivers a mesmerizing performance as Gregor Antonescu, a Romanian financier whose fraudulent empire is on the verge of collapsing. Pursued by both the media and the authorities, he takes refuge in the basement Greenwich Village apartment of his long-estranged son Vasily (Adam Driver), who has taken the new name of Basil Anthony.

There he intends to engage in a last-ditch effort to revive his fortunes by facilitating a merger with another company headed by Mark Herries (Zach Grenier) a closeted gay CEO who Gregor dismissively labels a “fairy.”

At first, Gregor--assisted by his loyal aide-de-camp Sven (Michael Siberry)--uses his charm and fast-talk duplicity to brush aside the arguments of Herries’ accountant (Brian Hutchison) that the numbers don’t add up. But he reserves his most shameless tactic until the end of the evening, when he dangles his attractive, bohemian son as sexual bait to entice his rival into signing off on the deal.

This is one of the more provocative if outlandish aspects of the play, which doesn’t fully succeed as either a family drama about the troubled relationship between father and son or as an indictment of ruthless capitalism. But it hardly matters, as the playwright’s gift for witty, cutting dialogue is well in evidence--it’s delivered by a first-rate ensemble under the finely tuned direction of Maria Aitken.

First and foremost, of course, is Langella, who conveys his character’s cunning, amorality and larger-than-life personality with sublimity. He relies, of course, on his forceful physical presence and booming, stentorian voice. But he also delivers a performance of masterful comic timing and physicality that is endlessly entertaining. Watch, for instance, the subtly mincing manner he suddenly adopts when trying to convince his business rival that he is secretly gay.

Equally fine is Siberry, as the loyal lieutenant who carefully looks out for his own interests every step of the way; Grenier, as the savvy businessman who succumbs to his baser instincts; and Driver, sympathetic as the son who eventually rallies to his father’s aide in spite of his own socialist leanings.

As is typical of Roundabout productions, the production elements are impeccable, particularly Derek McLane’s beautifully detailed set and Kevin Adams’ expressive lighting.

American Airlines Theatre, 227 W. 42nd St. 212-719-1300. www.roundabouttheatre.org.

Review: The Submission

Sep 30th

Playwright Jeff Talbott clearly knows the territory that he explores in The Submission. Having had his previous efforts presented at numerous theater festivals, he’s well in a position to lend verisimilitude to this darkly satirical portrait of a gay male playwright who invents a fictitious African-American female identity for himself in order to get his new work accepted by the Humana Festival.

Unfortunately, despite the sort of in-the-know references that regular theatergoers will appreciate—such as one character commenting on the commercial viability of a four character, one-set play, which this one happens to be—The Submission doesn’t exactly provide any revelations when it comes to the deeper aspect of its subject. Much like David Mamet’s Race, the main point being made here is that all of us, even liberals and minorities are, gasp, just a little bit prejudiced.

It’s not that the taut comedy/drama isn’t sharply written. Talbott has provided pungently amusing dialogue for his characters, who include struggling playwright Danny (Jonathan Groff), whose latest effort concerns a single black mother and her son struggling to survive in the projects; his lover Pete (Eddie Kaye Thomas), always ready with a wisecrack; Emilie (Rutina Wesley), the young black actress who Danny asks to assume his made-up identity of “Shaleeha G’ntamobi”; and Trevor, Danny’s friend who strikes up a relationship with Emilie.

But the well-drawn characters aren’t enough compensation for the more contrived and unbelievable aspects of the story, such as Danny’s repeated assertion that he and Emilie will become rich if their plan succeeds. Really? That will certainly come as news to most members of the playwriting profession.

The play’s certainly been given an impressively slick production courtesy of director Walter Bobbie. The performances, too, can’t be faulted, with Wesley--best known for her regular role on HBO’s True Blood--particularly compelling. But while admirable in its willingness to take on the sacred cow that is the presumed liberalism of the American theater scene, the play seems more designed to posit its intellectual arguments than provide any emotional resonance.

Review: The Bald Soprano

Sep 28th

With some exceptions, absurdism doesn’t age particularly well. The impact of what was shocking and avant-garde decades ago is reduced by the endless mediocre imitations that have followed throughout the years. Such is the case with The Bald Soprano, Eugene Ionesco’s one-act “anti-play” (the playwright’s description) about language and middle-class life that is now being revived by the Pearl Theatre. While the production displays a loving attention to the work’s detailed and purposeful deconstruction of its targets, the work comes across today as an extended sketch whose satirical points are repeated ad infinitum.

Set during “an English evening” in “an English interior,” it depicts the interactions among two suburban couples--named in pointedly bland fashion the Smiths and the Martins—as well as the Smith’s maid, Mary (Robin Leslie Brown), and a fire chief (Dan Daily) who unexpectedly drops by “on official business.”

It begins with the Smiths sitting in their cozy parlor, with Mrs. Smith (Rachel Botchan) attempting to make small with her distracted husband (Bradford Cover) who at first responds only with clicking noises of his tongue. Eventually they’re joined by the friends the Martins (Brad Heberlee, Jolly Abraham), who don’t seem to quite recognize each other despite the fact that they’re married.

The playwright claimed that he was inspired to create the piece while attempting to learn English, and the dialogue mirrors the sort of banal phrases that one encounters in language manuals. As the play proceeds, the language further dissolves into a series of non-sequiturs that are even more ridiculous than the preceding exchanges.

For the play to work today, it would have to be presented with the sort of atmosphere and imagination that went into the Broadway revivals of such (admittedly far superior) Ionesco plays as The Chairs and Exit the King. Although ably acted by the ensemble and featuring a nifty set by Harry Feiner that includes a rear wall that appears to be upside down, director Hal Brooks’ production never quite captures the work’s anarchic spirit. Although it’s good to see The Bald Soprano receive a professional production—in more than thirty years of theatergoing, I’ve never before come across it except on the page—it will best be appreciated by academics and completists.

New York City Center Stage II, 131 W. 55th St. 212-581-1212. www.nycitycenter.org.